Memories brought from the tropics

Visiting the tropical territories is becoming more common among us. For example, last year 10,000 Biscayans came to this destination as tourists, trips or cooperators. Foreigners from the tropical territories that inhabit our villages can also become a source of infections when they return after the holidays of their villages of origin. As a result, malaria, helminthiasias and other infections from tropical regions are proliferating. However, the problem is not the same number of tropical infections in the Basque Country, as it is not yet too large. The most worrying thing is the lack of habits that we diagnose and treat this type of infection. Having a fever and discomfort after a long trip and having to meditate on the doctor is frequent until the diagnosis is well focused. On the other hand, it is regrettable that most of these infections are preventable if concrete preventive measures are taken and often do not worry about it.

Our health organizations must adapt as soon as possible to the changes taking place in society. Therefore, they have a role in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infections of external origin.

What can we catch in the tropics?

If after visiting the tropical paradises we have a fever, when going to the doctor it is very important to inform them of the trip. In most cases it is flu, another respiratory infection, or urinary infection, which we can take both in the tropics and at home. But once conventional infections are ruled out, it can be a symptom of yellow fever, malaria, schistosomiasis or other exotic disease, and to realize this the doctor must know where we have been so that he can complete the diagnosis. We must give the doctor all the details of the trip: how long we have been, when we have come, what vaccines and antibiotics we have received, where we have traveled and what we have done. All these data are very valuable for correctly orienting the diagnosis, as they have much to do with disease transmission.

Atypical traveler fever from the tropics advises, first, the diagnosis of malaria. Malaria is a very serious disease, but after being diagnosed and treated early, most patients are cured. If this is not a malaria, the doctor should investigate other alternatives: recurrent fever, yellow fever, dengue, etc.

Another typical symptom of going to the doctor after the trip is diarrhea. 20-50% of travelers suffer and fortunately 95% of cases will not be very serious. This type of diarrhea is due to toxigenic serotypes of E. coli bacteria. It starts during the trip or just comes back and only lasts a couple of days. In 5% of cases, however, other more serious diseases are dysentery or cholera. The main symptom of diseases caused by amoebas and other protozoa abundant in the tropics is also diarrhea.

Large parasites, specifically helminths, often produce subclinical infections, whose main symptom is anemia. Many times we suffer from these infections without realizing unspecific symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue.

What determines the geographic extent of the infection?

The key is the transmission. Some unknown infections here, such as malaria, lomin disease, filariasis or yellow fever, are endemic in tropical territories, that is, infection rates remain approximately the same among the inhabitants.

The parasites that produce these infections have complex life cycles: they have to be in the human being in the middle of their life and in the other medium in another being. The malaria parasite, the protozoan Plasmodium, reproduces for a time in our erythrocytes, but cannot stay in a single hostel and will have to go in search of another being that completes its reproductive cycle, specifically to the stomach of the mosquito Anopheles. There also parasites multiply and the cycle is left when infected mosquitoes die to another human being. Thus, all these infections are transmitted by people or animals infected by mosquito bites, flies or other arthropods (Table 1)

These mediators are called biological vectors and are necessary to extend the infection and keep it in a territory due to the proliferation of parasites within the vector. The warm and rainy climate of the Tropics is ideal for the growth of these transmitting species. In our case, however, these vector arthropods do not present an optimal state of setting and growth of the larvae, so parasites cannot complete their life cycles. Therefore, cases of these infections are scarce and always from other territories. Biological vectors are very specific mediators, that is, each parasite will be transmitted by one or a few species. Therefore, in the absence of specific intermediaries the infection will end.

However, as can be seen in Table 2, other infections that we can take in tropical territories do not require vectors. Dysentery, cholera and traveler's diarrhea or hepatitis A, for example, are caught by contaminated water or food; schistosomiosis and other helminthiasis by bathing in contaminated water; AIDS, hepatitis B or syphilis are transmitted by sexual contacts and tuberculosis or air meningitis.

Most of these diseases are universal, that is, cases of diseases that can appear anywhere in the world, but the rates of infection (morbidity) in tropical regions are much higher than here. In these cases poverty is the key. Poverty, in addition to the lack of health facilities, causes the accumulation of people, lack of hygiene and nutrition and sexual confusion. Lack of nutrition causes immunodeficiency in humans, which increases sensitivity to infections. Because of lack of health care, these infections are not treated early and become a source of infection for other people. Until this vicious circle is broken, poverty will determine the geographical extent of many global infections.

Where to go, bring

Figure 1 represents the risk of infection in each territory. This takes into account the infection rates of the disease (number of infected per 100,000 inhabitants). Therefore, when the source of infection is large the risk of infection will be higher. This risk depends on the destination of the trip. For example, the risk of malaria in Africa, although the percentage of infected people is equal, is higher for the cooperative than for the tourist. The latter will travel a week, will sleep in luxury hotels and will travel the cities with little contact with its inhabitants. The cooperative, for his part, will work for about two months in some village of the tropics, living and spending the night with its inhabitants. Some of these inhabitants are a source of infections, and Anopheles mosquitoes, vectors of malaria, are much more numerous in the villages and therefore have a higher risk of infection.

Preventive measures and recommendations before travel

There are three general ways to prevent infectious diseases: 1) eliminate the source of infection; 2) cut the transmission and 3) protect infected humans. The first route depends on doctors, since diagnosing cases of infection and treating them properly reduces the source of infection. In order to use the other two options it is necessary that each one participate. In most cases, we must take personal hygienic measures to cut off transmission of infections in the tropics: not eating raw food, always drinking bottled water, whitening fruits, etc. To avoid stings of arthropods we must also wear suitable clothes and shoes and throw in the insecticide room. The use of condoms in sexual relations with the inhabitants of the tropics is essential, taking into account the rates of AIDS infection and hepatitis B, since the risk of getting sick is high.

We also have the possibility to receive vaccines or antibiotics that protect us against certain diseases before traveling. It is often advisable to update vaccines taken as a child: tetanus, diphtheria, polio, hepatitis A and hepatitis B, since in many regions of the tropics they are more abundant than here. Although we are small protected against these diseases, over the years we will lose immunity and we will have to take booster doses.

In addition, we may include other vaccines that are not used here, as long as the risks of the traveler6 are studied. The most important vaccine is yellow fever. Yellow fever is a widespread disease in both America and Africa and Asia. If it is vaccines against the epidemic, Japanese encephalitis and other diseases, but due to the scarce spread of these infections, we will rarely use them. In other cases, particularly in the case of cholera, although there is a vaccine, its administration is not recommended because of its low effectiveness. Consequently, the most direct way to avoid cholera is strict compliance with hygienic measures.

Unfortunately some infectious diseases still have no vaccine. Parasitosis (malaria, lomin disease, leishmanosis, etc.) are produced by parasitic animals. These parasites are much more complex than bacteria and viruses in antigens. Therefore, the search for vaccines to block these antigens is very difficult and at the moment we do not have effective vaccines to prevent parasitosis, despite the research being done in this field.

Vaccines are not the only way to protect the population from infections. Chemoprophylaxis may also be done, i.e. taking antibiotics to prevent infection. In the case of malaria and up to the commercialization of the vaccine under investigation, the weekly intake of chloroquine of 300 mg will be mandatory the realization of chemoprophylaxis. This prophylaxis will begin one week before the trip and must be completed four weeks after returning from the trip. To go to some territories, due to problems of resistance to chloroquine, we will take other antibiotics. It is very important that once the chemoprophylaxis has started the treatment will be carried out. Some people who take the antibiotic give in immediately after suffering the discomfort and many of them catch malaria.

It is observed that it is possible to protect itself from most tropical infections, but to determine the preventive measures it will be necessary to carry out the corresponding study (Figure 2). In most cases, the risk of infection will depend on the duration and destination of the trip and the habits, tasks and behaviors of the traveler. In addition, doses of vaccines and antibiotics should be adapted to the traveler's age, health status and other characteristics.

As said, it is most logical to consult the doctor before the trip, especially when the stay is long. For co-workers, immigrants, sailors and other workers it is also worth seeing the doctor after the return, even if there are no symptoms. For ordinary tourists, on the contrary, it is very convenient to make a pre-trip consultation, at least for information, but no systematic reviews should be made after the trip. But if for some reason they have to go to the doctor, it is very important to mention the doctor of the trip, since in this way he himself will have a good indication to correctly guide the diagnosis.

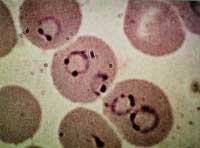

Exotic diseases are not difficult to diagnose. In the case of non-typical fever, it is sufficient to analyze a drop of blood under a microscope to show the presence of the parasite Plasmodium, Trypanosoma or Leishmania. Looking at a sample of stool under a microscope you can see amoebas or schistosomal eggs and other helminths (Figure 3). However, these clinical samples can be sent to reference centers for other diagnostic confirmation tests.

In many places in Europe and Catalonia, a few years ago they have dedicated themselves to the exotic diseases they have brought. By systematically analyzing some specific groups in the area (immigrants, voluntary cooperants and often trips to the tropics), extremely high infection rates have been found in the case of malaria or dengue fever, although most of these people have no symptoms. In our country and recently, in order to collect all the cases of infection brought, in some hospitals special consultations have been opened in which specialists in infectious diseases and microbiology collaborate. They are reference centers for the diagnosis and treatment of tropical diseases that are sent to patients from other health centers. They are also ideal places to solve doubts before the trip.

Parasitic Fever Biological vector Plasmodium sppAnopheles elicDiseases of LohandyBreiGlossina eulTripanosoma cruziLeishmaniLeishmaniLeisphyIospugs, the other phylum