Nicolás Atxukarro: meeting to cure

The U.S. government received an invitation to Alzheimer's. He was offered to be director of the Pathological Anatomy department of the Washington Federal Asylum. “I can’t go,” Alzheimer replied, “but I’m going to send you a young man who, being young, is as good as I am.” That young man was Nicolas Atxukarro, a 28-year-old from Bilbao.

He also died young, but his name is still alive in the Basque Research Centre for Neuroscience at the Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience. The motto of the center is “Know to cure” and could be that of the life of Atxukarro.

Born on Bidebarrieta Street on June 14, 1880 in a bourgeois and enlightened family. From a young age he was clear that he wanted to be a doctor. After completing his baccalaureate at the Bilbao Institute, at the age of fifteen he moved to Germany to study pre-university studies and study German well.

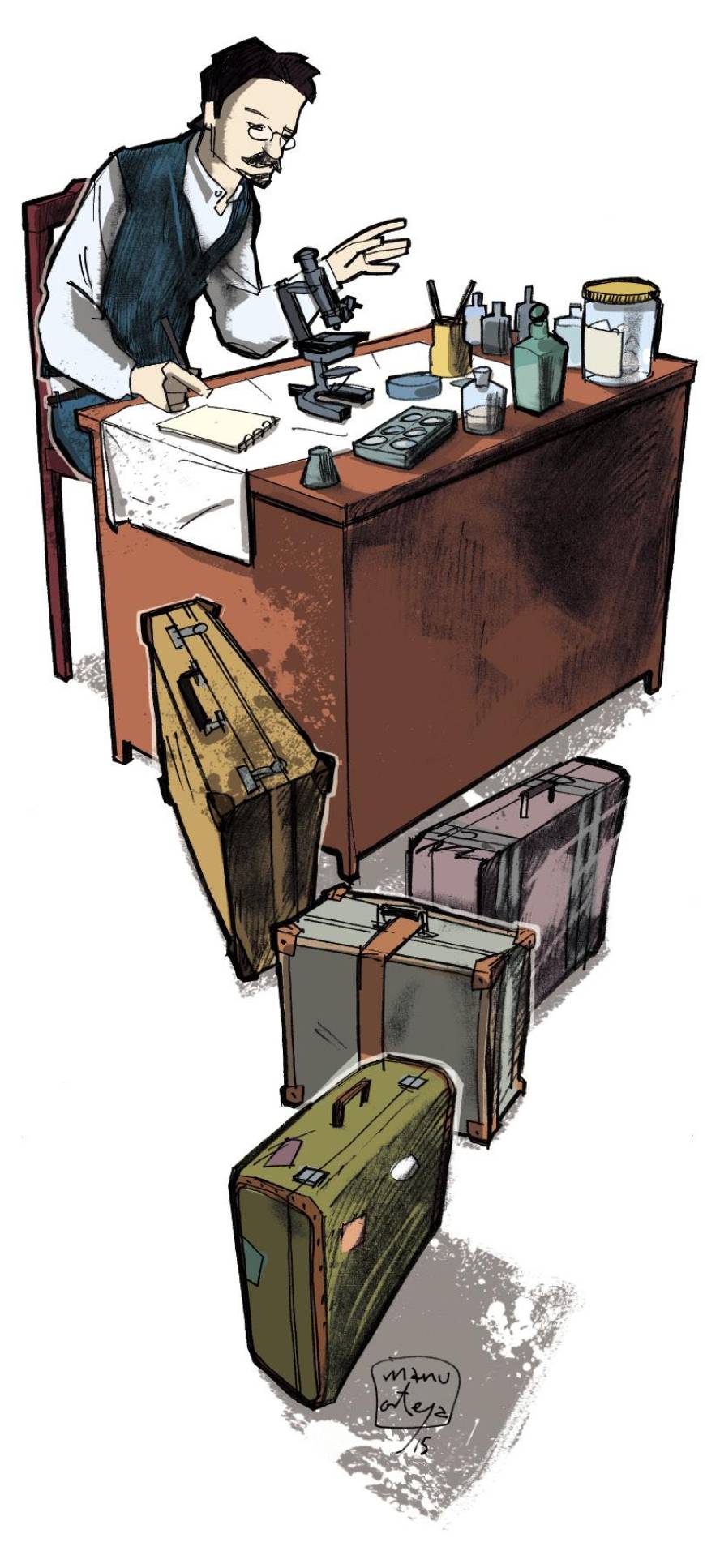

He later studied medicine at the University of Madrid. There he had as teachers Santiago Ramón y Cajal and José Gómez Ocaña, among others. He joined Gómez Ocaña's laboratory for the second year of his career. The University, however, does not fully satisfy Atxukarro's research spirit. When reading German journals in the faculty library, he considered that the scientific level of the Spanish university was scarce. At the end of the second year of his career, he packed his bags and returned to Germany with his brother.

He studied at the University of Marburg. Soon they had to return to Bilbao because their brother got sick. Tuberculosis took him a year. It was a hard blow to Atxukarro. However, he advanced in his studies. He presented and passed the exams to pass the third course of Medicine in Madrid. And the following courses he also did on his own.

Meanwhile, he worked at the Hospital General de Madrid, in the laboratory of doctor Luis Simarro. Gonzalo Lafora, member of it, said: “Atxukarro was immediately distinguished by his extensive knowledge and by his clarity and sympathy (...) He began to investigate the nervous system structure of low-grade animals and then analyze more complex structures of man… We soon realized that those who worked there Atxukarro was a man of great future.”

In the chamber of the house of Neguri he created a laboratory to continue investigating during the holiday period. However, work was not all. Unamuno said that Atxukarro once said: “It’s not all about running and naming, making money, living, enjoying, having fun…” He lived with passion and also with science. Lafora affirmed that “everything was joy and optimism in Atxukarro, always smiling at life… Yes, it was enraged with skeptics of the progress of science and, above all, with fraudulent or falsifying science”.

After the race was over, he packed his bags again and went to the leading laboratories in Europe. He worked in Paris, Germany and Italy and eventually traveled to Germany to the Emil Kraepelin clinic to study his new psychiatry. There he worked for three years in the laboratory of Alois Alzheimer investigating the neurological lesions of rabies.

Atxukarro stood out among the disciples of Alzheimer's and when the offer of the Washington Federal Asylum came, the teacher did not hesitate to send the young Bilbao.

Washington's experience was not of any kind. It was a hospital of about six thousand patients and there was no shortage of resources. At that time he published numerous works and was a pioneer in glia research: “Neuroglia is not just a supporting tissue, but an important element in nutritional and metabolic functions,” he wrote.

However, he was missing the house and, above all, left his beloved in Madrid, Lola Artajo. He returned two years later, leaving his friend Lafora in his post.

In Madrid it cost economic stability. He failed in the opposition to a square of the General Hospital of Madrid and began as a private doctor. Ramón y Cajal took him in his laboratory, but without salary. “I am dissatisfied,” he wrote, “of the lack of success of the official things of the laboratory and the hospital, and I am also thinking of abandoning Cajal’s laboratory, because it takes time and I don’t take anything out. I think I’m going to start working at the clinic and if I ever get enough, I’ll go back to experimentation; I find it hard to put that illusion aside.”

It gradually overcame the economic problems. And in 1911 he married Lola, with his family against him (Lola had a cousin, was older and was ill). That same year he took place in the Provincial Hospital of Madrid, and from the following year he led the Laboratory of Histopathology of the Nervous System.

He continued with Glia's research and, in order to analyze it well, invented a new dyeing technique: Atxukarro technique (tannin and ammoniacal silver). He also investigated the pathology of the nervous system in infectious and degenerative diseases and the influence of the sympathetic system on affective life and pathologies. It opened the way of modern psychiatry in Spain.

He was a great doctor. Ramón y Cajal himself also consulted him when he began with headaches. Cajal said: “He studied me and after a few words and measured picous euphemisms, he pronounced the sentence: ‘My friend starts the cerebral arteriosclerosis of old age. No need to worry! We are at the beginning and a good diet will prevent the progress of evil’.

It was clear that Atxukarro had a great future. However, the disease appeared and in 1915 he had to leave work. In 1917, increasingly disabled, he returned to Neguri. He thought about tuberculosis, but eventually self-diagnosed Hodgkin's disease. He died on 23 April 1918, at the age of 37.

“In addition to neurology and psychiatry, he taught us to be fraternal and understanding with the sick,” wrote José M, who years later worked with Atxukarro. Sacristan. The patient's lab and bed were very close to Atxukarro. His passion was to apply as soon as possible the technical advances in the clinic. Know to cure.

Bibliography:

ACHUCARRO OUTREACH MANAGER (2012): “Quick data of the visit of Nicolás Achucarro”. In neuroscience - Achucarro Basque Center for Neuroscience

ALONSO, J.R. “Achúcarro”. Neurociencia - El blog de José Ramón Alonso.

ESTORNES, I: “Achúcarro and Lund, Nicolás”. Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia.

MARTINEZ-AZURMENDI, H. (2001) “Dr. Nicolás Achúcarro (1880-1918)”. North.