Loco de Lacoizketa

His older uncle gave him the whim he wanted to drink fresh water from that fountain and sent his nephew to pick it up. The boy brought him water and a flower he found next to the fountain. His uncle thanked so much for the gift he gave him all the money he had at his disposal: three hard ones. When the mother of the boy learns, she rebukes her brother: “You will never go! For that hobby of collection you have lost your fortune and now the money I give you for tobacco you donate it for a flower. You’re crazy!”

He was not the only one who thought this way; José María Lacoizketa, parish priest of the town, has long been called in the town and its surroundings.

Born in the hamlet Lakoizketa de Narbarte on February 2, 1831. He was the eldest son of a noble family. He was a priest in 1855 and immediately went to Elgorriaga to care for the sick of cholera, where he remained there for 17 months. He then killed the parish priest in his hometown and was replaced at 26. He was parish priest of Narbarte for 31 years, until in 1888 he had to get sick and retire. He then retired to the Jarola palace of Elbete, where he had his sister. He died the following year, 58 years old.

Lakoizketa did much more than cures. “When my services assigned me –he wrote– to offer in this wonderful valley, I decided to devote myself to the research of natural objects, during all the free time they left me the multiple charitable requirements that the priestly work entails. The plants (...) were the ones that most aroused my curiosity, and so the botany has been the aim of my funny investigations and my ascetic and fascinating medals.”

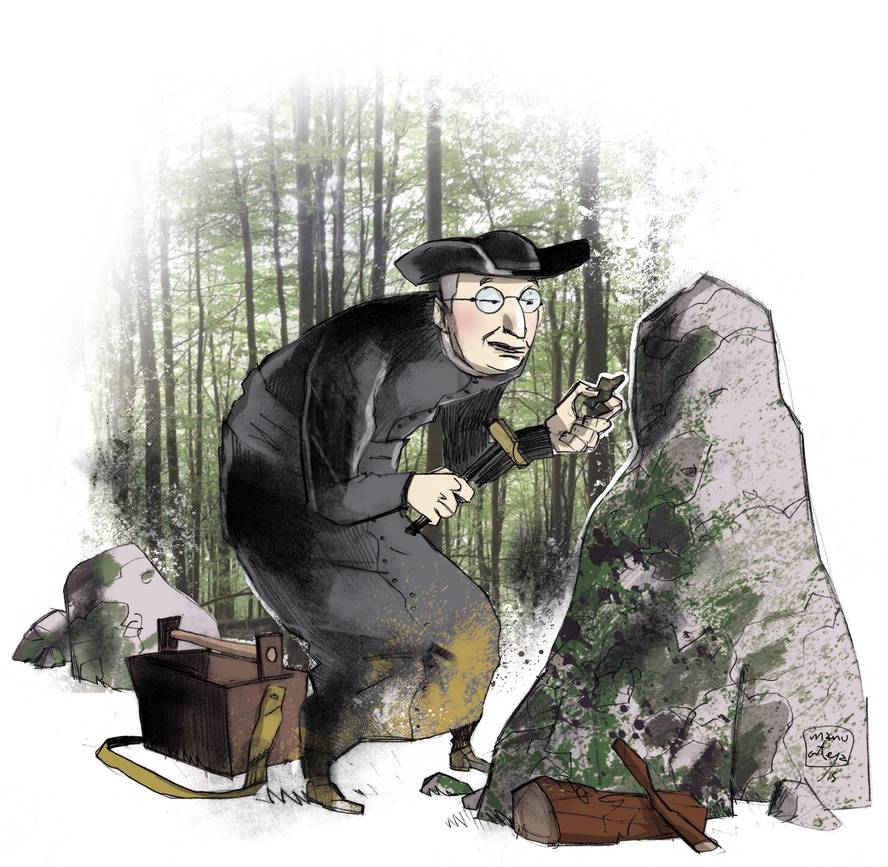

Whenever he could, both in summer and in winter, the parish priest of Narbarte came out with his brass box, zeio, chisel and hammer. And the neighbors saw the parish priest collecting herbs, losing in the gorge, or going up to places where no one went up and taking a piece of rock with a hammer and a chisel, like a treasure. He was the madman of Lakoizketa.

His friend Fermin Irigarai, a doctor from Irurita, wrote: His fondness for the plants was so much that he spoke them frequently, even with unknown people on the subject. Seeing some plant, whatever his person, he took the plant and observed it slowly, and told him everything he knew and felt about it.”

Although the citizens did not understand very well the behaviors of the parish priest, it had the name of botanist. He was a member of the French Botanic Society in 1877 and of the Spanish Society of Natural History in 1880. He was famous for being the greatest expert in peninsular northern cryptography (ferns, mosses, fungi and lichens).

Lakoizketa related to many other botanists, finding in their papers the names of 87. And among his collected and exchanged with other botanists, he formed a herbarium of about 2,500 species.

In 1884 he published Bertizarana's catalogue of plants: “Catalogue of spontaneous plants in the valley of Vertizarana”. In this work he collected 809 fanerogams and 495 cryptocurrencies, among which were 186 lichens. It was the largest number of lichen published in the State.

At that time, cryptoogams were little known and it was especially difficult to identify lichen. Surely Lakoizketa would have had to use the microscope and chemical reagents to study lichen. However, he became master of lichen. Of the 192 species published in Navarre, 186 published them.

He was also a linguist and he combined the basque language and botany he loved so much. “Phytographers do not forget the common names of the plants. They add to the description of the species the names given to them in the regions in which they live”, wrote Lakoizketa, in the prologue of the “Dictionary of the Basque names of the plants”, published in 1888.

And then: “You cannot deny the Basque Country all the right to be in this type of philoloo-botanical works, and it is compassionate the silence of the descriptive botany treatises on such an important subject. And it is not the Basque Country, which crosses the western Pyrenees, because it has no phytopathic interest, nor because its children, so bright in all their careers, have not excelled in the science of plants (...) This work comes to cover these lagoons and to meet these needs”.

In the dictionary appear the names in Basque of the sections and organs of the plants. Then come the plants. For each plant, first the scientific name, then the common name and the synonyms in Spanish, the common name in French, that of Basque and the synonyms, the etymology of the names in Basque and, finally, some notes on the plant. And “in order for my countries not familiar with scientific language to easily find the meaning of the names in Basque, an alphabetical index of those names will be put to the end.”

Lakoizketa says he collects in the dictionary the names given to plants in Bertizarana, Bortziriak, Baztan, Narbarte, etc. On the other hand, he acknowledges that the fact of wanting to clarify the origins of the names in Basque had some risks. “Etymologies can have a lot of arbitrary, much of ideal and true, if they are carried away by light fins of imagination.” To avoid it, a series of rules were put, but it could not be said that it managed to escape completely from the slopes of the imagination.

In any case, the value of the work done by Lakoizketa in botany and in the Basque industry is undeniable. Eusko Ikaskuntza also wanted to recognize the work of Lakoizketa's madman and placed a plaque in his hamlet in 1924: “Mr. Lakoizketa, son of a good house, is the greatest Basque of plant knowledge. A memory of the mention we owe to the Basques.”

Bibliography: Bibliography:

ANDUAGA, A: “Lacoizqueta Santesteban, José María de”. Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia

ETAYO, J. (2002): – J. M. M. Lacoizqueta”. Naturzale 17, 5-34

IBARGUTXI, F. (2006): “The parish priest of the thousand plants”. Diario Vasco.

LACOIZQUETA, S.L. (1888): “Dictionary of the Basque names of plants in correspondence with the vulgar, Castilian and French and Latin scientists”. Printing Provincial.

LACOIZQUETA, J. M. M. (1884): “Catalogue of spontaneous plants in the Vertizarana Valley”. Proceedings Soc. Exp. Dif. Nat.13: 131- 225.

OLLAQUINDIA, R. (1980): Three studies on Navarrese dictionaries. Fontes linguae vasconum: Studia et documenta 35-36, 319-352.

PÉREZ DE VILLARREAL, V. (1982): “Don José María de Lacoizqueta: the botanist (1831-1889)”. Ethnology and ethnography notebooks of Navarra39, 329-361.