The centered life of Gisella Perl

He took the two-day baby in his hands. He felt mild. He gave him a kiss, soft, on the soft face. He stroked his hair. He drowned. And he hid it under a pile of corpses that he hoped would be incinerated.

Gisella Perl was born in 1907 in Sighetu Marmatiet (then Hungary, now Romania). She was the first woman and first Jewish woman to finish high school in the village. I dreamed of doing medicine. Her father denied her because she feared that she would impede her faith and move away from Judaism. His daughter swore to him on a sacred book: “I promise, wherever I go, and in any situation, I will always be good Jew and true Jew.”

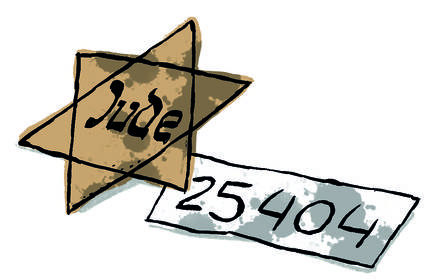

He fulfilled his dream and became a gynecologist. He loved his job a lot and he had a very good reputation. He worked until in May 1944 the Nazis invaded the region. They took 13,000 Jews, most of them to Auschwitz, including Perl and her husband and son. The daughter hid in another family's house.

Accumulated in cattle wagons, without water or food, they arrived at Auschwitz after eight days of travel. Perl was one of the five doctors Dr. Mengele chose to work in the “hospital” of the concentration camp. Knowing it alleviated his disgust a little, hoping to help his colleagues as a doctor. But he soon realized that there was no rendition for hope in that place. “Don’t worry about the work tools,” they said, while he took away the tools he brought, “you won’t have any.” No tools, no beds, no bandages, no drugs...

And the shortage of food was even more serious than the lack of equipment. “I had more work after the food distribution,” Perle said, “I had to tie the bloody heads with broken ribs and clean the wounds.”

He had to perform hundreds of operations without anesthesia. The two most frequent types of interventions were the women who started and the sutures of breast lesions. And for that I only had one knife.

He often tried verbally to alleviate the pain of the sick: “I listened to them with my voice by telling them nice stories, saying that someday we would celebrate birthdays again and someday we would sing again.”

Dr. Mengele ordered him to report all pregnant women, they would take them to another camp and give them more food and milk. “I was still naive,” Perl would write, to believe the Germans, until one day I was commissioned by the crematoriums, until I saw with my eyes what they did to these women. Several SS men and women surrounded them and beat them with their heads and barbarism, killed them, dragged them by pulling their hair and banging them in their stomachs with hard German shots. And when they fell, they threw them in the crematorium oven.”

When he saw him, he was stuck on the ground, unable to move, unable to scream, unable to escape. “Slowly, horror became a force, a fighting force, and that force woke me up and gave me the reason to live. I had to stay alive. I was in my hand to save all the women who were pregnant in my camp from a terrible fate; if there was no other way, the life of their unborn babies had been destroyed.”

He decided that there would be no more pregnant at Auschwitz. On dark nights, in the dark corners of the enclosure, on the ground, dirty, without a drop of water, he did what he had to do. “Always in haste, all with my five fingers, in the dark, in incredible conditions.”

One day Doctor Mengele gave him another order. She told her that pregnant women would stop dying and stop giving birth in the hospital. Yes, children would have to take them themselves to incinerate. He was happy with the news. Being able to deliver on the clean floor of the hospital was a huge difference to the health of these women, and if they ever managed to get out of there, they would be more likely to become pregnant again.

When Mengele returned, the hospital had 292 pregnant women. “He put himself in the needle, the smoker and the pistol in his hand, and two hundred and ninety-two women were loaded in a truck and thrown alive at the flames of the crematorium furnace.”

At the end of 1944 he was transferred to the Bergen–Belsen compound with other prisoners. There he remained until in April 1945 they were released by the British. She soon begins to search for family and finds that her husband and son have been killed, as well as other relatives, neighbors and acquaintances.

Hunted, he attempted suicide. But he failed and was moved to a French convent to complete it. He then moved to New York, where he lectured on the Holocaust and raised funds for refugees. There he was accused of helping Nazi doctors and violating human rights. But, thanks to the testimonies of hundreds of former prisoners who saved their lives, he proved that he did not.

“I didn’t want to be a doctor anymore, I just wanted to witness and voice what happened,” he said. But finally, in 1948, he was admitted as a gynecologist at Mount Sinai Hospital. She was the only woman. He became a specialist in the treatment of sterility. Between 1955 and 1972 he published nine articles on vaginal infections.

In 1978 he discovered that his daughter was alive and lived in Israel and left there. There he continued, from now on, as a volunteer at a hospital accompanying the births.

In the United States and Israel worked for about 40 years and helped over 3,000 children to be born. He wrote in his autobiography that every time he entered the delivery room he prayed: “My God, it owes me a life, it owes me a living child.”