History of the flying hunter who became a fisherman

What, how much and where do they fish?

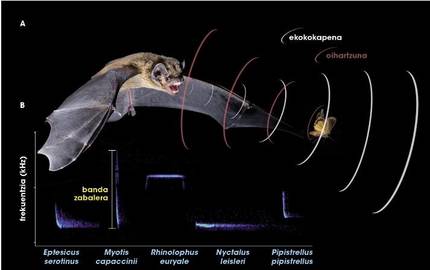

To answer these first questions, more than 3,000 excrements collected in a colony in which previously found signs of fish passed under my magnifying glass with the aim of finding scales and otoliths (Figure 1). The otolitos are solid structures of calcium carbonate in the equilibrium system that characterize the species. Among those thousands of excrements I identified 97 otoliths and, analyzing their morphological characteristics, concluded that all fish ingested by bats belonged to the exotic species of fish Gambusia holbrooki. Ganbusias are small fish that float on surface in freshwater and bittersweet areas, and that proliferated throughout southern Europe during the twentieth century. In the early twentieth century, since they were brought to fight malaria. On the contrary, I found fish scales throughout the year and concluded that the importance of fishing behavior in this colony is greater than expected.

The next step was to know where the fish fished, with two main objectives: to know the factors that enable fishing activity and how fishing activity develops. To find fisheries, I followed by radiotelemetry to the animals that ate fish. To do this, I caught 15 very long bats when entering the cave in the morning. After analyzing his excrements with a magnifying glass in the place, I marched with radio station to bats that more fish remains left (Figure 1). In the following nights I realized that the animals that followed shared a hunting ground: a large and deep artificial well of a golf course (Figure 2). To ensure that bats were fishing there, I launched the recording equipment. This is the first time that the dactilar bat is recorded in natural state fishing.

How to fish?

The objective of the second part of the doctoral thesis was to know how fishing activity is carried out. How is it possible for a ten gram bat to weigh? What technique does it use to capture fish and what differs from the insect capture technique? What type of quinada used to detect fish? To answer all these questions I did four experiments.

From insect hunting to fishing

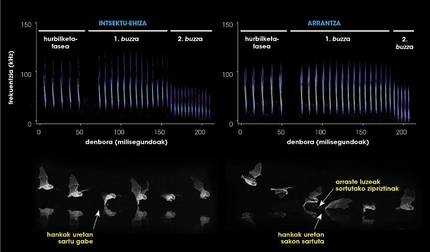

To learn what the techniques of fishing and insect hunting consisted of, I dedicated two types of hunting to dactile bats in their natural fishery: insects and fish. Then, patience. After fifty-two working nights I had the opportunity to record 135 hunting and fishing attempts (Figure 3).

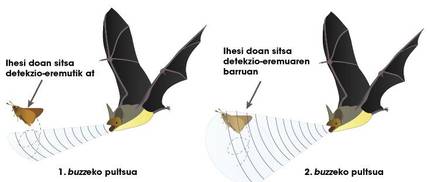

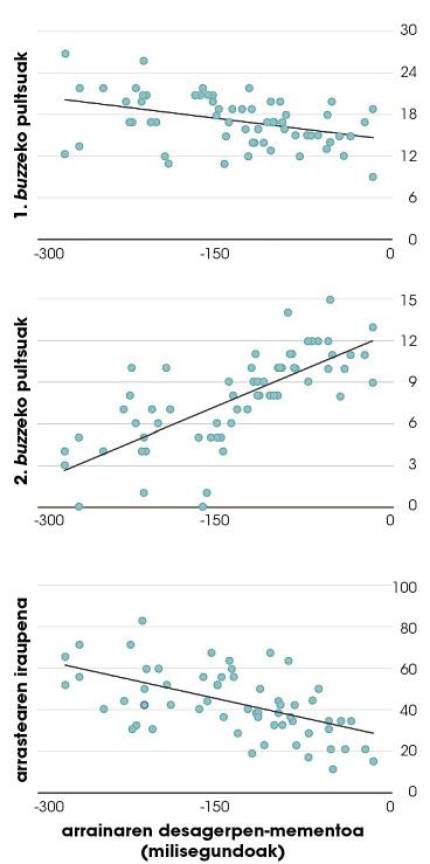

These recordings showed that the insects posed on the surface of the water are captured by the long fingers of the bats by a brief drag with the feet or with the uropatago (membrane between the feet). In the case of fishing, however, the legs are introduced much longer and the drag is longer. The differences are not only seen in the plane, but the sweeping pattern is also different (Figure 4). To understand the mechanism, let's stand for a moment in a pediment, in a ball match for couples. Imagine that the pelotari is bat, the ball, the sound pulse and the frontis, the prey. When the zaguero is fighting in Table 8, away from the frontis, the ball takes several seconds to go to the front and reach the other ball. However, when the striker is living in Table 2, the ball comes faster to the rival after the frontis and the game is much faster. The same happens with the sweeping of bats. As the loot approaches, the time since the sweeping pulse is emitted until it receives its echo decreases and, to avoid overlapping the pulses, it is necessary to accelerate the sweeping mechanism. Bats can change from 10 to 120 pulses per second at the end of a catch. This pulse acceleration that occurs at the end of the capture phase is called buzz and, in the case of these bats anglers, is divided into two parts of different characteristics: Buzza 1 and buzza 2 (Figure 5). In the case of the first buzza, the pulses have higher bandwidth and higher frequency, while in the case of the buzza 2 the bandwidth is lower and the frequency is lower. Therefore, the information that the bat receives from each type of pulse is different.

This doctoral thesis has shown for the first time that bats have the ability to modulate the two parts of their diver, extending a part according to interest and reducing the other. When catching insects, the importance of two buzz is similar, but when catching fish the 2nd buzza is much reduced and in some cases it disappears. This phenomenon has its explanation. Low frequency pulses have less directionality, which allows bats to assimilate information from a broader scope (Figure 6). Therefore, bats use the 2nd diver to know the escape manoeuvres of insects at the last hour, since the pulses of greater directionality would not give information about the destination of the insect. At the time of capturing fish, however, when the fish is found under water, the bat does not wait for a last minute escape manoeuvre and reduces the 2nd diver in favor of the 1st more informative diver.

Quinada

The use of one technique or another for the capture of insects and fish indicates that bats are able to separate the two pieces of hunting, and the next step was to understand how this separation occurs: to know what is the way to identify the prey as fish.

The first step to know the exact quinada was to know the type of stimulus to which the bats respond. For this, I studied the behavior of bats before three options. In a quinada, I created water waves without any visible prey. Another day I put a standing fish submerged in the water, with the lip high out of the water. The last inciso was a fish that ascended and descended, which, besides appearing and disappearing, produced waves of water. I realized that bats only responded to the stimuli that showed their prey, without paying attention to the waves.

With this information, I began to analyze the differences between the inactive fish and the one that disappeared, with the aim of knowing if they identified the fish from the morphology or the disappearance movement. I realized that the correct answer was the second option, since I saw that the answer to the two types of quinadas was similar to the response to insects and fish, that is, when a fish is standing, they attack it as if it were an insect, performing short extractions of the skin and using buzz 1 and 2 similar. When the fish disappears, however, they become deeper and longer trawls, leaving the diver in type 1 pulses, as in the catch of fish.

Modulation of the hunting technique

The technique used by bats for the capture of fish is more expensive than that used for the capture of insects, since the friction in the introduction of the legs under water produces a great loss of kinetic energy. Its use as a permanent hunting technique for the capture of fish is not, therefore, profitable if it is not a kind of mass capture. And to know how bats react when the prey disappears, I prepared a last experiment. I immersed the fish at different times of the cynegetic activity of bats and studied the modification of flight patterns and sweeping bats.

The response of bats was not of type yes/no, but gradual. In other words, the change in the moment of disappearance of fish and hunting patterns were related to each other (figure 7). Bats adjust the drag intensity to the uncertainty of the position of the prey and adapt it to collect the type of information they are interested in the sweeping pattern. This regulatory behavior can, therefore, be an important element that profitabilizes fishing.

The degree of delicacy of the senses outlined in this thesis and aviation suggests that fishing is an important factor that can influence both the evolutionary history of the dactilar bat and the current survival of the species.

They live in the dark, we treat them with distrust, and they often displease us. However, we still have much to learn, admire and enjoy them. Try to fly in the dark by catching a fish under water. Don't get caught!

Bibliography Bibliography Bibliography

Acknowledgments of thanks

I thank Ignacio and Joxerra for making this work possible, and all the team for being there when I needed it, especially Antton. Finally, we want to thank all the people and entities who during these four years have participated in this thesis, which have been many! This study was funded by the Basque Government (BFI-2009-252), UPV/EHU (INF09/15) and the Ministry (CGL2009-12393).