Stuck in the energy transition

The energy transition is a dream, an ancestral hope and promise, reducing the use of fossil fuels and replacing them with clean and renewable energy sources. We have long understood that this transition will be fundamental, among many other things, to deal with a crisis or a climate emergency that is now flying. But the latest data offered by Gaindegia does not seem to have made much transition.

“We have evolved a lot technologically,” says Gaindegia coordinator Imanol Esnaola Arbiza-, leaving coal behind in fuels and starting to use cleaner sources. Several agents have also been created to take advantage of clean energy sources (Goiener, Nafarkoop, I-ener) and some municipalities are developing decentralized microproduction systems (Lizarraga, Gares, Izaba, Oñati). But we continue to have a great dependence on oil in industry and our everyday habits. Consumption of petroleum fuels has returned to pre-crisis levels. And continuing with the system that exploits old energy sources, we will hardly make the transition.”

Santi Ochoa of Eribe Usabiaga, director of Goiener, agrees: “There have been advances, but at the level of Euskal Herria we are very pathetic. Our dependence remains impressive, something that is very evident in the data of Gaindegia. The data is unfortunate.” Ochoa de Eribe believes that we are in this situation for many reasons: “On the one hand, in society we don’t have that sense of urgency. On the other hand, our socio-economic structure has been based on industry. And we don't have very solid strategies. The Basque Government has developed several plans, from 2014, from 2020… but we are always behind Europe”.

Energy in Euskal Herria

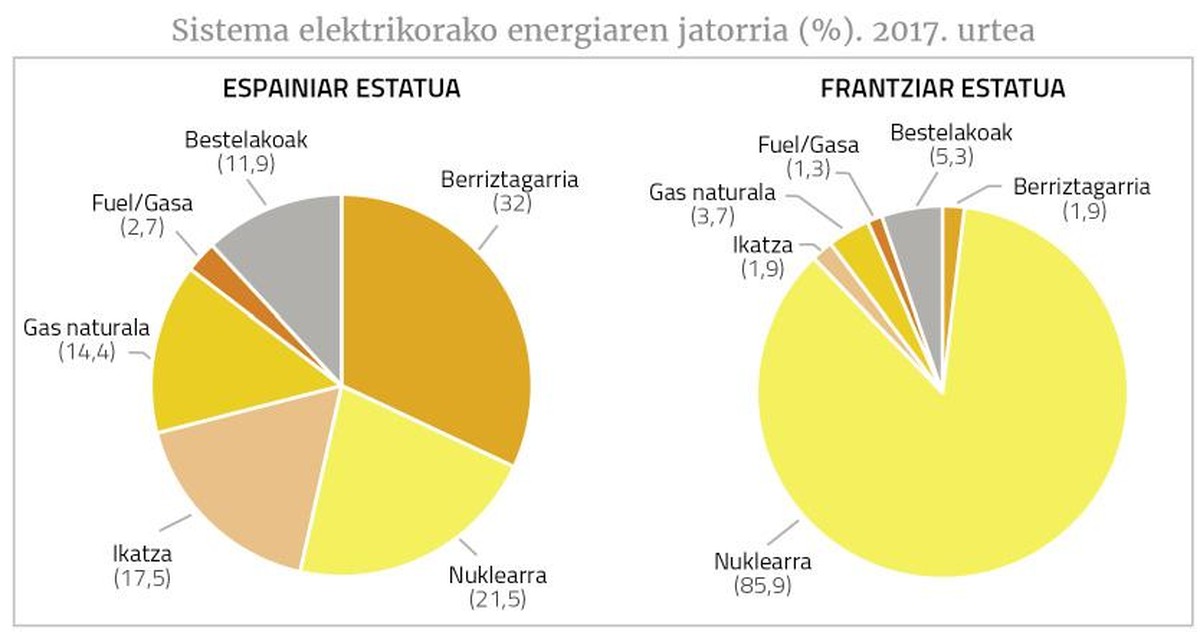

More than 90% of the energy consumed in the Basque Country comes from external sources. Much of the electricity comes from Spain and France. And the sources are very different in both states. In Spain, the dependence on polluting sources such as nuclear, coal, fuel and gas stands out. And in France, the electric system is based on nuclear energy.

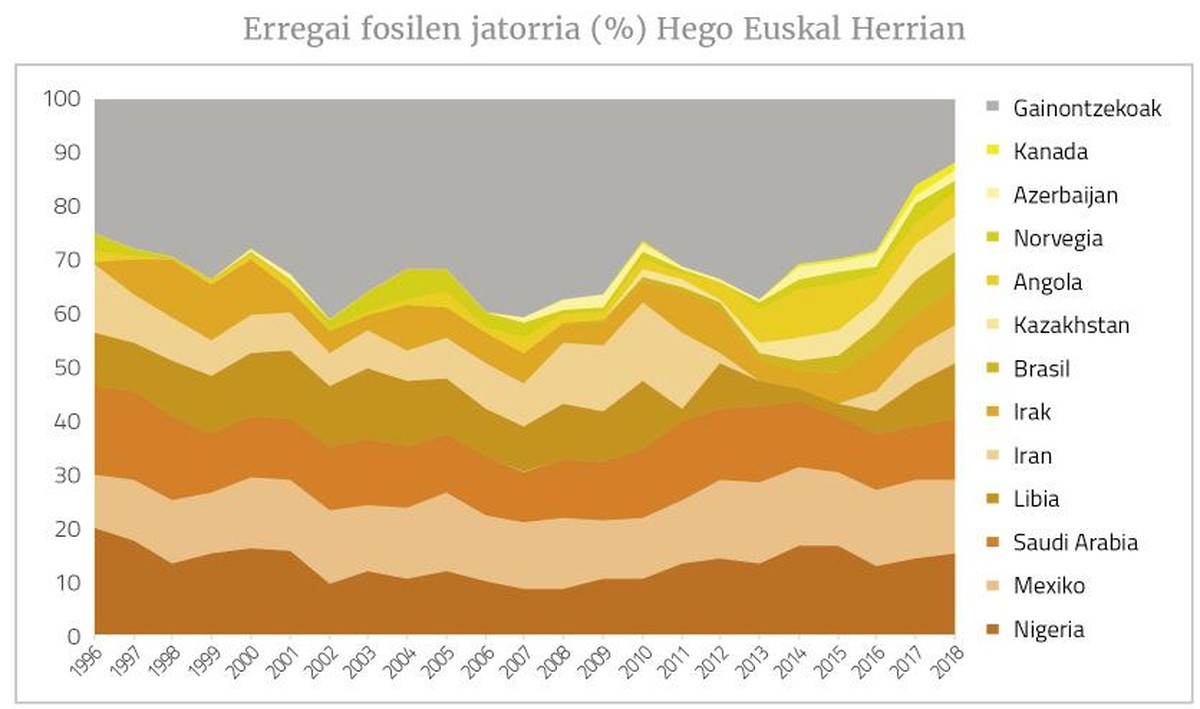

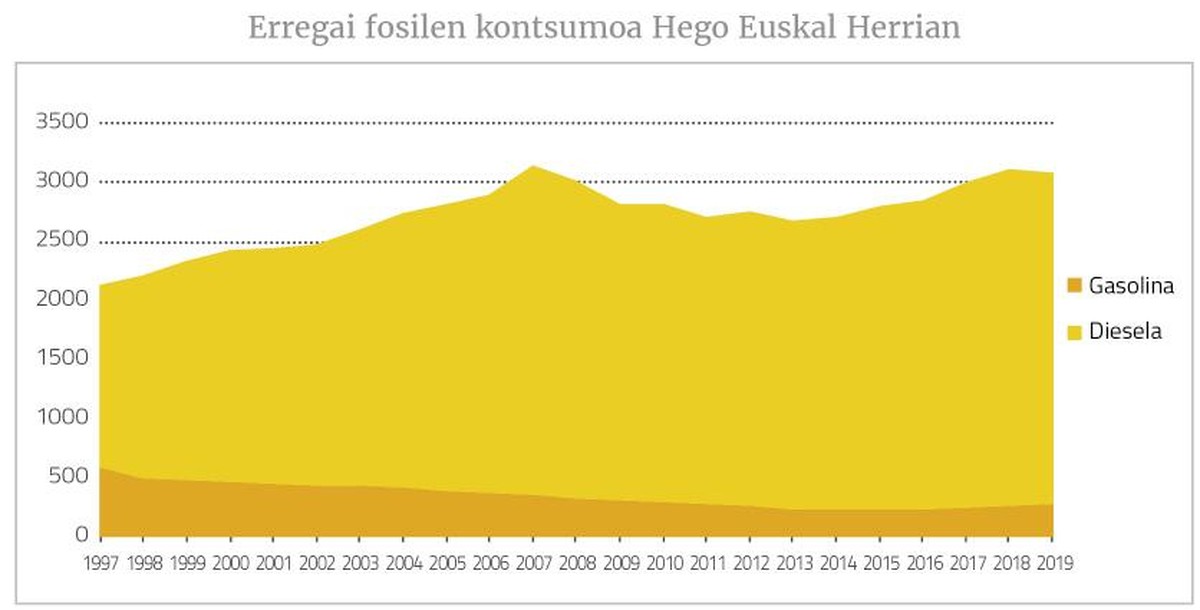

We bring fossil fuels from all over the world, especially from Africa, the Middle East and America. In terms of consumption, although the 2008 crisis was a slight decline, in 2018 it was the largest historical consumption of diesel in Hego Euskal Herria and, if the Gaindegia forecasts are met, it will only be reduced slightly in 2019. Gasoline, on the other hand, will increase, placing the consumption of fossil fuels in 2019 in historical highs, with a predominance of diesel higher than the maximum of 2007.

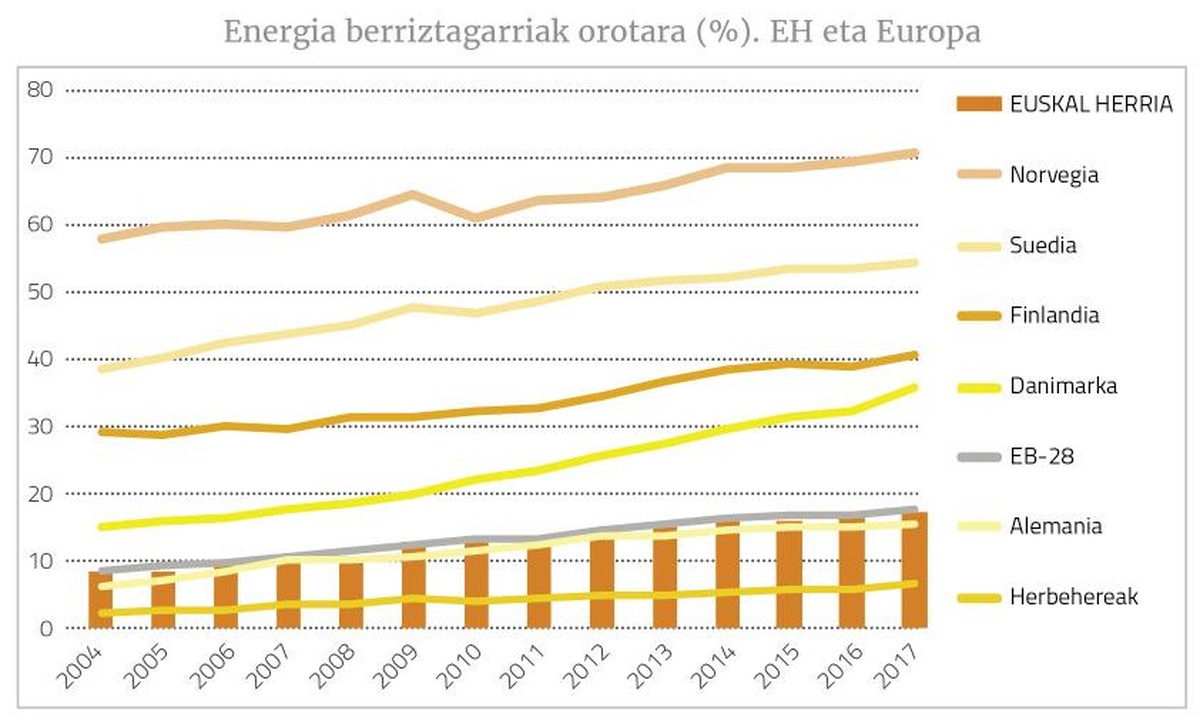

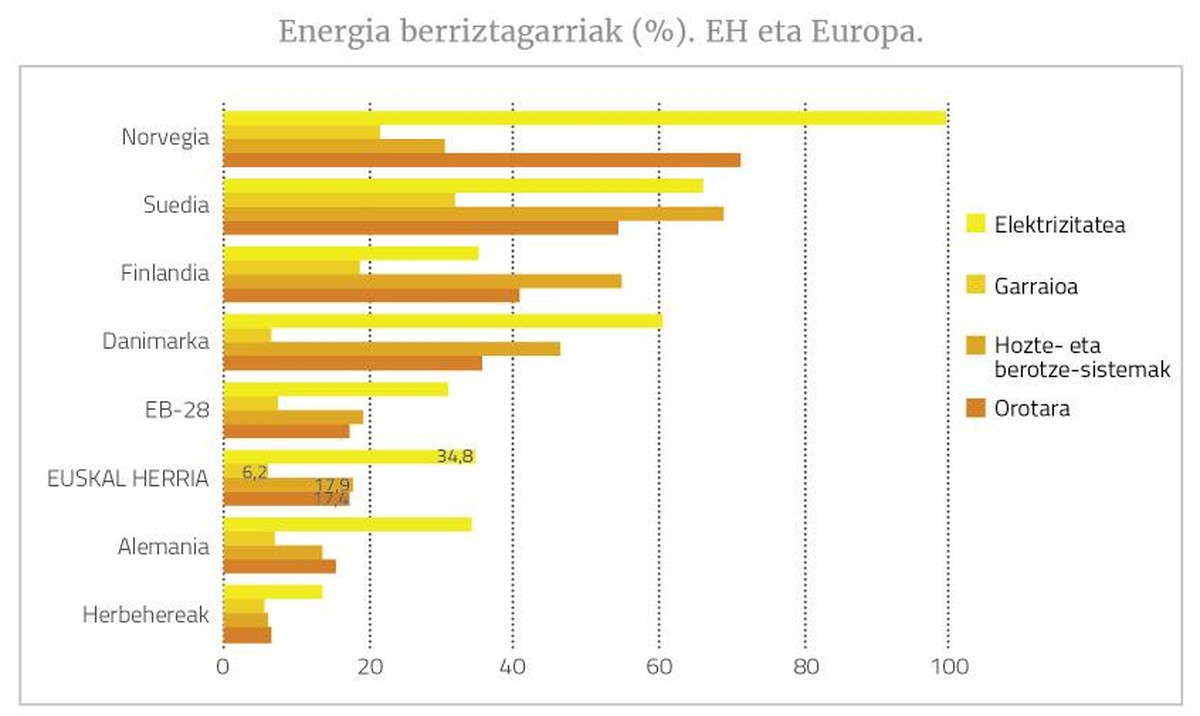

The rates of renewables in the Basque Country are similar to those in Germany and the European average, but far from the Scandinavian countries. Given the uses of energy, it is observed that the simplest transition is taking place in the field of electricity. Sweden has made 100% of electricity come from renewable sources, not the rest. The hardest thing seems to be transport, but Sweden, Norway and Finland are also getting strong compared to others. Finally, Sweden, Finland and Denmark are ahead of cooling and heating systems. In total, Germany and the Netherlands are far from the countries of reference, as well as Euskal Herria.

Northern countries show that more can be done in the transition and Euskal Herria is lagging behind. There are also some differences between countries. “On the one hand, they are very lucky as a resource,” says Ochoa de Eribe. “Norway, Finland and Sweden, for example, have huge water resources, from a biomass point of view, through forests. On the other hand, the population proportional to the surface must be taken into account.”

But Eribe's Ochoa also sees other differences: “What models and customs exist at the social level to do things. For example, last year I was in Denmark and one of them told me that there they have very internalized about going to the platoon. There is a lot of wind, and if you only go racing, the wind hits you full, while in the platoon all together you have the support of the team. That culture is very internalized, and that drives you to reach agreements, cooperation, etc. And there you can see that both the left and the right are driving quite similar energy policies.”

Our resources

The energy produced in the Basque Country comes mainly from renewable sources, but does not cover 10% of consumption. We have limits on resources, but there is still a long way to go, according to Ochoa de Eribe: “On the one hand, we need to know what our resources are and how to exploit them sustainably.” Our resources include waterfalls and forests. “The energy of forest wood can be used, stressing the need to do so sustainably. We will have to see if that is profitable or not, but there we have a hot resource that can be exploited and not given enough attention.”

There is also solar energy. “Even if the radiation here is small, it can be used to get electricity and heat water, so we use it.” The wind sees more problems: “In Navarra there are more options, but especially in the autonomous community, the areas most suitable for the installation of wind turbines are protected areas. If we want to preserve these natural spaces it is difficult to install wind turbines. And many times we talk about getting into the sea, but there we also have problems, because the continental shelf is very small. In the North Sea there are plenty of wind turbines, but about 40 kilometers from the coast. Here we cannot. We would have to put them much closer and they would look, we do not know what influence they would have on bass fishing, etc. Something must be sacrificed. What level of sacrifice we want, we have to put it on the table.”

“It’s not easy,” says Ochoa de Eribe, “and it’s not just a technological solution. However, we have many things to develop. For example, district heating systems can be created in small villages. Also at the electricity level you can do many things, for example, encourage so-called distributed generation, etc.”

Another key is energy efficiency. “If our buildings did not consume so much energy, perhaps with small renewables, with which the building itself can generate, it would be enough and we would not have to bring anything from the network,” explains Ochoa de Eribe.

“There’s a lot to do,” he says clearly. “With alternatives like Goiener we want to start from a young age to show that it can be viable. So we will not get rich, but the goal cannot be to enrich us. But how to make that change in our economic system? There we lack much.”

Esnaola considers public policies essential to change the situation: “The implementation of renewable energy requires strong public policies. The Spanish State has suspended for several years the policies of promoting alternative energy sources. And although in Hego Euskal Herria we develop our technical capacity, this Spanish public policy has greatly curbed the development and implementation of renewables. In Iparralde the situation is different. Although France is heavily dependent on nuclear power, it has public policies that take into account the transition. However, the French state has to cut public spending and, for the moment, it is not enough to put public resources in that direction.”

“Basque citizens are used to deciding what the energy model should be,” says Esnaola, “but both our well-being and social cohesion are built by ourselves. Therefore, if we want to preserve this balance in the future, we will also have to introduce the energy transition into the Basque equation. Without pushing from us, we will hardly reach a new situation,” he says. “This new situation must be influenced by people and entities. In addition to influencing public policies and budgets, there is much to do to change everyday practices. We have a long way to wake up.”

More than technology

And it is that our transition to make, in addition to the technological, must also be socio-economic and cultural. “Let’s try to put renewables in the territory as much as possible, with respect to both the environment and society, etc., but that also has its limitations,” warns Ochoa de Eribe. “The solution is not only to innovate. We also have to think about the kind of life we lead and that many things we take for good may not be like that.”

Transportation is one of the most serious problems we have. The dependence on fossil energies is enormous and in the near future great solutions are not seen. “There is a lot of talk about electric vehicles, says Ochoa de Eribe, but how many electric vehicles should we put? The same number as current cars? Are there enough minerals to produce batteries? And what kind of infrastructure do we need?”

“Can we keep thinking that living in Vitoria is normal and going to work at Baztan every day? And what problems does it generate?” continues Ochoa de Eribe. The problem, in short, is not just energy. “Energy is a cross-cutting point in society, in all societies, throughout history, and often a more global vision is what we lack. The problem is how we use resources and perhaps we should question many of the things we have internalized in our societies.”

For example, seeing from which countries we bring fossil fuels generates great concern to Ochoa de Eriber. “What is happening right now in Algeria and Ecuador is directly related to it. And if to meet the needs of the first world it is necessary to destroy other countries, they are undone. There are Syria or Libya, and now they try with Venezuela. Once dissolved, they will be incorporated through companies or neighboring countries to obtain the resources there.”

“The energy crisis and the climate emergency are there, but the emergency situation is much broader,” said Ochoa de Eribe.

For Esnaola the energy crisis is also a structural crisis: “We have built our business models, services and lifestyle on a certain energy consumption.” And it represents a conflicting future: “There is nothing more to see how world geopolitics is. Oil wells, oil and gas tracks, rare minerals, etc. have become a source of conflict. Balance and solidarity do not seem to prevail in the world of low oil. From Euskal Herria, in addition to external influences, we must adapt our public practices and consumer trends.”

In this sense, Ochoa de Eribe sees some prince of hope in our society: “We have realized that there are small and very small initiatives that, although not very spectacular, are resulting. People look for something different. Although this trend is not the majority, something is moving. And that is for me, from the point of view of the transition, almost the best.”

“We started with the intention of driving responsible creation and consumption of energy, but we have realized that this is much greater: the economic model, and how to change the model of society. And we see that the most important key comes from there.”

Looking ahead, “I imagine that a society will have to get used to doing things with few resources and, consequently, will achieve a new relationship with resources and the local environment. And I think we will see more and more renewables, but also different socio-economic models.”

Esnaola also has hope: “We can live well without sparks imported by oil, but in that we also have to learn all.”