Detective Smit seeks the imprint of shock theory

Today, most geologists accept shock theory and it is extended to society. That is why it seems that it should be of old. But it is not so old, as it was first proposed in 1980. However, before that came the relationship between Jan Smit and the theory of shock.

The 1970s is incipient. At that time, Smit was researching in southern Spain. He focused his attention on the fossils of planktonic foraminifers, finding something striking: until reaching a layer of dark clays, there were many species of formanifers and many of them. Upon reaching this layer, however, all disappeared sharply. Later, in younger layers, the foraminifers reappeared, but they belonged to other species and, compared to the previous ones, were less developed. Smit, at the K/T limit, thought that the key should be in this layer of mud, that is, in the layer that determines the end of the Cretaceous and the beginning of the Tertiary.

He also studied other outcrops of that time, finding in all of them that special layer. And in everyone the same thing happened with the foraminifers, even in the ravine of Grede. This ravine, located near Caravaca, in Murcia, is ideal for studying the final era of the Cretaceous, with the most complete succession of layers in Europe.

In 1973-74 Smit modified his strategy: "I discarded fossils and decided to study the composition of the rocks." In 1977 he sent samples from the Grede ravine to a laboratory for neutron activation analysis. This allowed him to know that some elements were in abnormal concentrations. Specifically, the amounts of nickel, copper, chromium, antimony and selenium were much higher than normal. Smit suspected they could have an alien origin.

Iridia, decisive footprint

Among these elements, the laboratory did not mention iridium, and Smiti did not find it strange, since on Earth there is hardly any iridium. Two years later, however, he was greatly surprised when he discovered that another sample of the K/T border found an iridium. Alvarez was father and son and the show belonged to the Italian region of Umbria, the Gubio. The Alvarés proposed on Earth that iridium was caused by the collision of an asteroid.

Smit sent his sample back to the laboratory in order to fix himself well on iridium and then they did find iridium. Apparently, when analyzing the sample for the first time, the laboratories considered the iridium data a mistake and did not consider it. The second analysis clearly showed how much iridium there was: 28,000 ppt. "Tell us: Five times more than in Gubbio," says Smit.

One of the options for there to be so much iridium is for an asteroid to hit the Earth. But it can also be due to a supernova. "I was a supporter of that," he admits, "a supernova can push dust clouds to Earth." But he consulted with some astronomical friends who told him it was impossible. It had to be by asteroid.

In autumn 1979, a meeting on the K/T limit was held in Copenhagen, where Jan Smit and Walter Alvarez (son) met. Since no one else believed that at the end of the Cretaceous the species had disappeared as a result of the collision of an asteroid, they became friends. In December, Alvarez sent Smit an article he wrote for the scientific journal Science. The title was: Extraterrestrial Cause for the Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction.

Smit sent the results of his work to the journal Nature. The title of the article was very similar: "An extraterrestrial event at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary". Nature published the article in May, a month before Science, but Smit certainly did not proclaim the paternity of collision theory, as the Alvarez were the first to relate iridium to the asteroid shock.

Some say that if Smit knew in the first analysis that the sample had iridium now the shock theory would be called Smit's theory as well. Anyway, as Smit told us, when the articles were published, in 1980 few geologists believed that extinction had been sudden: "They thought the loss was staggered."

Where is the crater?

Smit did not stop and continued to seek evidence. He soon found another trace of the asteroid's impact: In the lower K/T boundary sheet of the Grede ravine, he discovered a large number of crystallized microspheres. "They are components of the asteroid, fused and subsequently solidified. I wasn't the first to find iridium, but I was the first to find microspherulas." He also published his article in Nature.

Later he also discovered quartz crystals. Like microspheres, quartz crystals were thrown out when the meteorite hit the ground. According to Smit, only an atomic explosion or an asteroid shock can produce quartz crystals with such deformation. "A volcano can't do it."

In fact, the main opposite to collision theory was (and is) the hypothesis of volcanoes. According to this hypothesis, the extinction of the Cretaceous occurred as a consequence of the volcanoes, there were favorable signs. In addition, for supporters of volcanoes, the theory of shock had a great vacuum: where was the crater generated by the shock?

Smit tells us how they were found. In fact, some geologists working with oil companies have long known that there was a large crater in the Gulf of Mexico on the Yucatan peninsula. But, on the one hand, they thought it was a volcano and, on the other, they did not relate it to the K/T limit.

Thus, many geologists investigating the K/T border continued to look for the crater and had indications that it should be near the Gulf of Mexico.

Meanwhile, in 1989-1990 Smit made other discoveries such as the tectita. Tectitas are the driest minerals known, with little water. Its formation requires enormous pressures and temperatures, for example, those that occur when hitting an asteroid against the Earth and are thrown with impact force. The larger ones are near the crater and the smaller ones go further. He later saw that the distribution of the keyboards corresponded to the location of the crater.

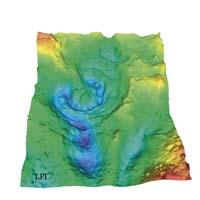

In 1991, geologist Alan Hildebrand proposed that the crater of the Yucatan peninsula was the one he was looking for, the Chicxulub crater. The key to this conclusion was special sediments on the Texas Brazos River. According to Hildebrand, these sediments came to this place because of a gigantic tsunami. The origin of the tsunami should be in the Gulf of Mexico. And what could cause such a large tsunami? For collisions of an asteroid, for example.

Everything coincided: gravimetric studies, age and composition of the rocks, traces of the tsunami around the Gulf of Mexico, distribution of tectitas, cenotes (dolinas around the crater), microspherulas, iridium...

Smit has told us that "we have found all the clues we expected to find." For example, soot could be expected at the K/T limit, and yes, in the layers of the K/T limit the soot caused by fires caused by the impact of the material that was projected when hitting the asteroids is evident.

Collision of ideas

There is, however, that the geologist does not accept the theory of shock. One of the best known is Gertatu Keller. In his opinion, the dinosaurs disappeared due to volcanic activity, for example, the Indian altiplano Deccan is witness of a terrible volcanic activity and the time coincides with the disappearance of the dinosaurs. In addition, he does not believe that dinosaurs were suddenly lost, he is convinced that decay began earlier. And it does not deny the fall of the meteorite, but it was the main cause of the loss of dinosaurs.

However, for Smite Keller's arguments are not credible and Smit is able to answer each of Keller's explanations. "I have no doubts," Smit tells us. "We have found that 65 million years ago an asteroid fell on the Yucatan peninsula and was the creator of the Chicxulub crater. We have many clues worldwide that confirm it. I recognize that it is more difficult to prove that all these species disappeared as a result of that shock." And, firmly, it ends: "But there is no evidence to suspect that dinosaurs were already losing and, after the crash, there is no dinosaur foot, none."

He now works in the Gulf of Mexico researching the traces of the tsunami. Can you find any evidence that gives more strength to the theory of shock?