Walking through the history of history

It is seen with a clear example. The inventor of the telescope was the Italian Galileo Galilei, which is written in academic books. However, Galileo directed an already invented device (the goggle) to the sky, whose contribution has been a fascinating application. But then who actually invented the glasses?

After consulting several sources, the name of Hans Lippershey appears. However, it is not very clear whether he was right or not. But the Dutch government paid 900 guilders for the invention to Lippershey and turned it into military secret. How do you know if you deceived the government?

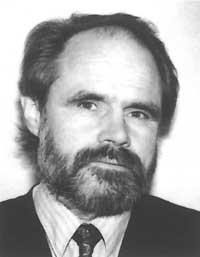

In most cases there is no 'single truth' and, although there is, it is not known what it is. Perhaps the best approach is historiography, that is, the collection of duly organized historical documents. In fact, many scientists have completely abandoned research and dedicated their entire lives to it. Many of them have already been discussed in this magazine. On this occasion, the place is occupied by a person dedicated to historiography, the Danish writer and physicist Helge Kragh. "At my origin I wanted to become a physics researcher, but little by little I liked the historical and philosophical aspects more. Also, I have no capacity to be physical," he said.

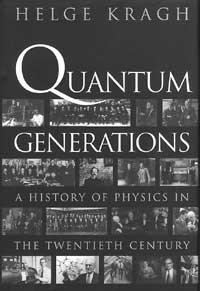

Currently Kragh is professor of science history in Aarhus, Denmark, where he has two main functions: teaching and historiography of science. Princeton University Press has gained fame in the latter field a few years ago. He asked him to write a book on the development of 20th century physics. At first Kragh thought it was an easy job and accepted the order. However, as soon as he started working, he understood that it is not possible to write all this in a single book and decided to replace it with a "brief and selective story".

The result is a book of almost 500 pages, Quantum Generations. "It was a three-year job. Since I had to use indirect information sources, the problem was not getting a certain amount of information. On the contrary, the biggest problem was to decide which of these information should be taken and excluded." Book published in 1999. In the text, in addition to the usual concepts of physics, he describes many experiments that did not have good results. In general, in the teaching of physics these experiments are discarded, but to follow the course of the history of physics it is essential to accommodate these studies.

Context

However, science in no case is an isolated activity, but an area that develops through social needs and interests. Therefore, Kragh carefully describes political and economic history. Do not forget the XX. The main theories and changes produced by 20th century physics have occurred in the first quarter of a century.

Science transformed war and war science. This interaction occurred both in the academic and social spheres. During World War II, for example, many scientists fled Nazi Germany, some forced by ideology and others by ethnic problems. The importance of atomic theory at this time is evident, directly affecting the investigation of weapons, especially the production of bombs. Nazis and Americans embarked on this investigation, but they are not the only example. Scientific research also had a great influence on the politics of Mussolini and Stalin.

In addition, these investigations were conducted according to the needs of governments and nuclear research became a state secret. To a large extent, ownership of these secrets was key to deciding who would win the war. The cases of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are significant, but they were also influenced by less established experiments and theories. In the Cold War, as for nuclear weapons, both sides were balanced. This situation is due to the passage of scientific secrets.

All these facts are collected in the book Quantum Generations. On the other hand, Kragh has also analyzed in depth the anti-scientific trend that emerged in the 1960s. It was a very important social factor. Today, the socialization of science has clear advantages, but it has not always been so. How did the physicists of that time overcome the crisis?

Most of the material Kragh needed was written before he wrote the book. But the real goal of history is not to bring new things to light. "In the book there is a lot of data, and most of them I received from the literature already written, that is, from specialized articles and books. Historical research often requires the collection and reorganization of previously known but not associated data in the appropriate context."

Each author offers a new interpretation of the story, and after this great work, the opinions of readers can be very critical, especially among those who work in this field. Therefore, the philosophy of the global approach is important. In the case of the book of Kragh was dangerous, XX. Because many scientists who have participated in 20th century physics are alive.

Several readers have missed some scope of physics. For example, material is missing on liquids (both classic and quantum). In addition, no other important aspects such as chaos theory have been mentioned. However, in general, Kragh has formed a very good book and has had a great reception among physicists. In short, in addition to historiography, Kragh is a physicist. "I have no reason to complain about the criticisms received. All the people who have come to me have been very positive, some have been enthusiastic," he said.

History in science subjects

Academic use of historical texts in the teaching of science is unusual. However, scientists are forced to learn from previous mistakes and advances, not knowing whether or not the most recent theories are acidic.

In the same way, history can have unforeseen contributions for science students. This idea is defended by many disseminators and historiographers, including Helge Kragh. "Yes, history creates, among other things, a didactic effect. Many times it is better to explain concepts and theories through the history in which they were developed. Therefore, in the teaching of science history plays an important role."

However, this method of teaching is faced with the rejection of students: history is not always viewed with good eyes in classrooms or science. However, the situation beyond teaching is not the same. When both are offered pedagogically, the general public accepts them enthusiastically. Some scientific studies, for example, acquire great attention in the press and television, which has a great impact on public opinion.

But this can have two faces. People on the street want to know what the advances of science are, but they may not want to understand the basis of those advances. Public interest encourages socialization to the detriment of other issues. The example is the genome (and genetics in general). In recent years, scientists conducting genetic research often appear in the media. Those interested in physics perceive that this echo is very strong. Is it a matter of fashion or is it really important?

"It is true that genetics and molecular biology are widespread and of great interest to the public. I do not think it is a mere consequence of the interest of the media. In areas such as genetics there have been significant advances in recent times. I don't know if this group will be the 'science of the next century', but I think it's one of the breakthroughs, surely more than physical sciences, says Kragh.

From now on?

The evolution of science is a historical process with society. Quantum Generations is a book that reflects this evolution well. throughout the 20th century. However, for this time the media were very developed, so the comparison with the situation of the previous centuries is usually a good exercise.

For many disseminators, the difference lies, among other things, in the relationship between science and technology. "Yes, the 'link' between science and technology is today very strong, stronger than it has been. It is an important part of modern science, especially physics." Today science is rapidly developing the instruments it needs, while the theoretical advances made to meet the needs of technology are also rapid.

But somehow the limit can be close. Several hypotheses suggest that the theoretical concepts of science to be developed have already been developed. John Horgan, a regular contributor to Scientific American magazine, is the defender of this hypothesis. Physics, last fundamental theories. Its development dates back to the first half of the twentieth century. Is theoretical science exhausted? What can be expected from current physics?

"That is a very broad and difficult question to answer! First, I hope that technology will be even more advanced; then I expect a constant advance of basic knowledge, especially in astrophysics and cosmology. But I never think physics is definitive and answers every question about the universe. 1.