Is it impossible for Elgorria to disappear from the world?

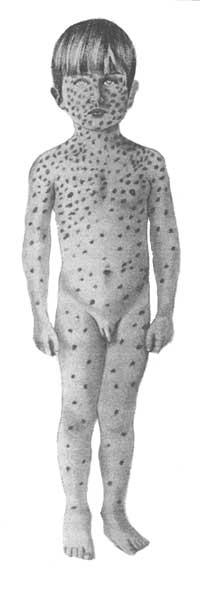

The answer to the first question is based on scientific reasons: the disappearance of measles is possible. The disappearance of Baztanga in the world showed that it is possible to eradicate contagious diseases. Although there are notable differences between baztango and measles, there are also epidemiological similarities. In both cases, the causative agents are viruses (which produce well-known skin rashes) and is a very useful feature for epidemiological observation. Both diseases give us immunity for life. There are no chronic asymptomatic carriers or animal reserves of these viruses in humans.

Since 1963 we have an effective and safe measles vaccine. Until recently it has not been used systematically but there were technical difficulties (accumulation, transport and cold sales chain that was necessary to adequately protect the viability of the vaccine virus, practically impossible to obtain). The vaccine we currently use is more heat stable and in 3-4 weeks it can freeze its power without cooling at tropical temperatures.

An economic advantage has been added to this technical breakthrough, since the measles vaccine, per dose, costs only 450 pesetas.

As seen, the scientific reasons for the possible disappearance of measles seem powerful. Let's go ahead and address the second question. Do we have to put an end to measles? In times when global resources are so scarce, is it worth spending money and using human forces against this disease?

The answer in this case is also positive; measles should disappear, for health and even economic reasons.

Health reasons: health reasons

Measles is an important cause of unnecessary suffering, premature mortality, and enormous expenses. Except in isolated populations, measles is almost universal and most people suffer from the disease before age 15. Measles, in any situation, can be a source of serious complications such as diarrhea, encephalitis, atrial otitis, pneumonia, etc.

Economic reasons for economic reasons

Prevention through the measles vaccine has resulted in an annual savings of US$130 million in 1963-1972. Currently, an annual savings of about 500 million dollars is estimated. The cost/benefit ratio of measles vaccination in this country is estimated at 1:10. And the benefits of this investment would be even greater in developing countries, since the morbidity and mortality due to measles in the latter is much greater.

It is more difficult to answer the third question about the disappearance of measles. Did we get it? Will we be able to gather enough social wills around the world to eradicate this disease? It is fair to think that for a long time we will probably not get it.

Although opinions on this problem do not always coincide, it is undoubtedly a goal that is worth eradicating the disease. And it is working in a lot of institutions and nations, in this sense, so that within 1990 all children from all over the world can have a systematic immunization (or vaccination) against the five diseases.

Will we get the measles to disappear?

If we want to give a realistic answer to the question we must take into account some differences with respect to measles. Measles is a very contagious disease that manifests sharply and spreads rapidly. These characteristics differ greatly from smallpox, since a slower extension of this disease and the adoption of drastic measures allowed them to control quite well.

This difference between both diseases means that any program aimed at the disappearance of measles would be essential to obtain and maintain very high immunization rates (perhaps higher than 90%). Although the disappearance of smallpox was achieved through the healing and control of individual cases, the rates of immunization of the general population did not exceed 50%. Measles immunization should be applied successfully and at the same time to children from all regions of a given nation to achieve that goal. To eliminate the transmission of measles, it is necessary to have a sustainable primary care infrastructure capable of systematically integrating the majority of the population.

There is one last important difference: the greatest difficulty involved in the observation of measles with respect to marginalization. It is little wonder that measles is mixed with other diseases that cause rashes or redness of the skin, and that, on the other hand, measles does not leave the mark or sign easily recognizable in the long term, as occurred with the scars of smallpox (in these cases it was known that the person was immunized against smallpox). Therefore, if reliable data is not available, it will be necessary to carry out serological investigations from time to time, which logically implies an increase in costs.

I think the worldwide disappearance of measles deserves a special effort and effort. International organizations dealing with public health will have to fight for it, but we cannot say that we will get it immediately. It is a test of success, will and general initiative and every case of measles that appears will serve to measure errors. From now on, not a single case of measles!