Rudolf Virchow: medicine for society

He was 27 years old when he went to Silesia Alta. Whoever saw him marked him for life. 500 kilometers from his laboratory in Berlin, he saw his fellow countrymen die with typhus and hunger. It was at the request of the government, because they were going to have to deal with this typhus epidemic. He was there three weeks. A report detailed the situation and proposed solutions: “It can be summarized in three words: full and infinite democracy.”

Rudofl Virchow was a doctor. And even though I was young, I already had a name. He did important research at the Charite University Hospital in Berlin. He described leukemia and enrolled it a couple of years earlier and studied cardiovascular problems, including the terms thrombosis and embolism.

The Prussian Government expected more medical solutions. But Virchow saw clearly that the problem was mostly social. Faced with the epidemic, a Polish minority and impoverished collective, the education, freedom and prosperity of their daughters, was the recipe of the young doctor. “Share it well: it’s not about treating a patient with typhus with medicines or regulating food, housing or clothing. It is a culture of millions and a half of citizens who are at the lowest level of moral and physical degradation. With a million and a half, mitigating measures are useless. If we want to solve the situation we must be radical.”

And these radical proposals by Virchow were, among others, education in the mother tongue (Polish), the formalization of Polish, democratic self-government, separation from church and state, the elimination of taxes on the poor and the imposition on the rich, the creation of agricultural cooperatives and the construction of roads.

His father wrote: “Now I am not a partial man, but everything, and my medical ideas coincide with my political and social ideas. As a natural scientist, I can only be a Republican.”

Nothing more to return from that hard experience, he went to the streets of Berlin to participate in the revolutionary attempt of 1848. And he created the weekly Medizinische Reform to claim social medicine. Almost she wrote the entire magazine alone. “Medicine is a social science and politics, in short, is medicine on a larger scale,” he said. Or: “Doctors are lawyers of the poor.”

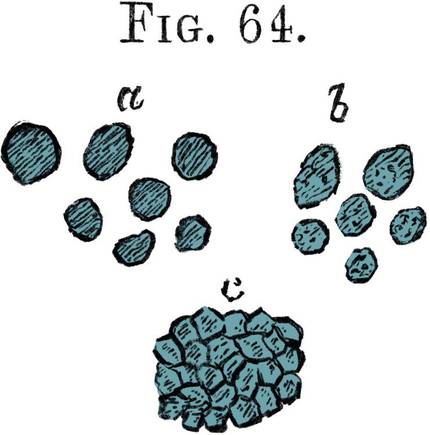

He was expelled from Charite and had to leave Berlin by participating in the protests. He moved to Würzburg and received the first chair of pathological anatomy in Germany at his university. There he published his most famous work: [Cell pathology]. In this work he defended that the basis of diseases is in cells and made famous the phrase omnis cellula e cellula: all cells come from cells. He did not find him, but a friend who, being Jewish, had to investigate in the shadow, Robert Remake; but Virchow introduced him as his.

In 1856 he returned to Berlin, where he was director of the Pathology Institute that had just founded in Charite in the next 20 years. He worked a lot on issues related to citizens' health. She discovered trikinosis, and because of it they started inspecting meat. He invented the word zoonoses for diseases that went from animals to people. He also described and named the spina bifida. He wrote about 2,000 scientific papers.

I didn't think microorganisms caused disease. “If I live my life again, I would do my best to show that germs are not the cause of tissue disease, but choose diseased tissue as habitat,” he said. And he also opposed the hand-washing tips of Ignaz Semmelweis.

For Virchow, germ theory was an obstacle to curing and preventing disease and epidemics. I thought that the origin of the epidemics was social, so political solutions were needed: “Epidemics are social phenomena with certain medical aspects.”

“All epidemics indicate a social shortage,” he said. According to Virchow, inadequate social conditions made people more vulnerable to climate, infectious agents and other causative factors. “May the rich remember that in winter, when they are sitting in front of hot heaters, with Christmas apples to the youngest, those apples and the chargers that brought heating coal died in cholera. It is very sad that thousands of people have to die in misery in order to live a few hundred.”

And to prevent and overcome epidemics, social transformation was as important as medical intervention. “The progress of medicine probably extends the lives of human beings, but even by improving social conditions we can achieve this result, better and faster.”

He proclaimed that health was a right and represented a public health service: a network of health-care centres with doctors and State-paid staff.

He also worked in politics. In 1859 he was elected to the Council of the City of Berlin and a member of Reithstage, from 1880 to 1893. Otto von Bismarck was there a fervent rival of the “iron chancellor”. Once he denounced that the military budget was so large that he did not invest in public health, the chancellor became so angry that he proposed a grief for that medikutxa. The doctor rejected the offer.

Throughout his life, he researched, lectured, wrote, edited, worked in politics and fought. He was not an unemployed man. It was never and would never be. At the age of 81, he jumped off a tram that still didn't stop and broke his hip. He died shortly after.