Karl von Frisch: Dancing with the bees

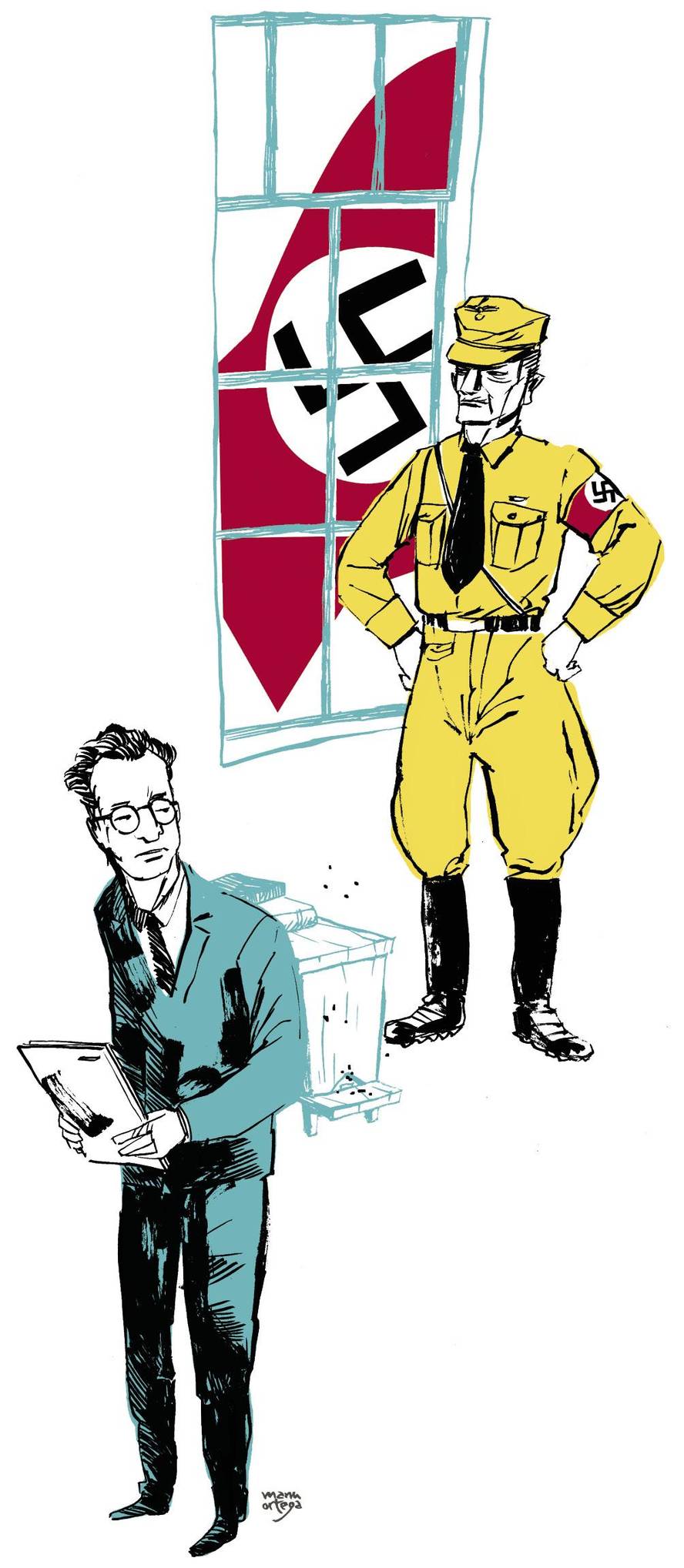

Munich, early 1941. Seeing that letter coming from the University, he suspected. “...we force you to mark yourself, according to the law of 1937, because you do not meet the requirements to be a teacher.” She had previously been warned because in her laboratory she took too many Jews. And there they met a Jewish grandmother of origin, so he was not a bear. This time I saw no escape.

Several comrades tried to support him to stay in college. But finally the bees would save him. In those years thousands of hives were losing all over Europe, due to the parasitic fungus Nosema. The problem was serious, especially in times of war, when food was scarce. The loss of pollinators so important to food production could be a disaster. The “Special Nosema Commission” was created, which was authorized by the Ministry of Food to continue investigating. According to the president, “Karl von Frisch was the most successful bee researcher in the world.” He was not wrong, 30 years later he had been awarded the Nobel Prize for his work with bees.

Karl von Frisch liked animals since childhood. He was born in Vienna in 1886. In a school diary it is collected that in the room came to have 123 species of animals: “9 mammal species, 16 bird species, 26 cold-blooded terrestrial vertebrates, 27 fish and 45 invertebrates”. Von Frisch's passion was to observe his behavior. And he also published some observations in a magazine for amateur naturalists, such as when he discovered that his marine aquarium anemones, despite having no eye, responded to the light.

Following in his father's footsteps, he began studying medicine at the University of Vienna. But his path did not realize and, in the middle of the third course, he left Medicine and moved to the University of Munich to study Zoology. In his doctoral thesis he investigated the luminous perception of shields and the change of color. He discovered that the shields have on their head a “primitive third eye” that changes color depending on the light they receive.

Contrary to what was then thought, he showed that the fish had an ear. When he gave the food to the txistu, the fish learned to tie the txistu with the food; and when they heard it, they sought food, although there was no food.

He began experimenting with bees around 1912. To begin with, I wanted to show that they could see the colors. It was thought that insects were not able to do so. However, von Frisch did not understand then why the flowers had that color if it was not to attract pollinators. He placed a blue cardboard among others of various gray tones and on the blue a tray full of syrup. The bees joined the syrup with the blue cardboard and once the syrup was removed they kept going to the blue, even changing the location of the carton. Bees perfectly distinguished colors.

And he realized something else. When the trays were empty, occasionally only some exploratory bee appeared. But if any of these explorers found a full tray, the bee table was immediately filled. Von Frisch thought that the scouts passed some warning to the hive.

One day in 1919, the scout discovered the tray syrup, marking with paint the dots, to go to the hive. “I could hardly believe what my eyes were seeing. The scout danced in a circle as the adjacent bees played with the antennas. Then the bees went straight to the tray.” That dance was the warning that they were going to look for food and saw that the explorers taught them with the smell what they had to look for. In this way groups were formed for each of the sources discovered by the explorers.

Von Frisch, next to Wolfang Lagoon, owned the family bees at his home to spend the summer in the Austrian Alps. There he did most of his experiments. In 1944, when Allied bombers began attacking Munich, members of von Frisch's team, they took from the laboratory all the material they could and moved von Frisch's family to the house. Soon after, the university laboratories and von Frischen's house were destroyed.

That summer made her discoveries about bee dance more surprising. Instead of placing the syrup tray near the hive, it occurred to him to place it about 150 meters. He smelled lavender to the tray and placed two trays of the same smell, one near the place where the syrup was placed and another near the hive. I wanted to see how the bees that received the notice searched. He hoped they would start looking for the hive environment. “To my surprise, no bee came to the tray next to the hive, while the one far away was filled with bees. Was it possible, in his ‘tongue,’ to have a ‘word’ for distance?” he would write.

After eleven experiments of this type, he discovered that the food was near or far, they danced in one way or another. When I was close they made it in circle and from 50 meters, making eight. In addition, this eight contained information on distance and direction. The further, the more slowly they formed the eight and marked with the direction of the straight part of the dance the angle that formed the food source with the sun.

“The bee dance looks comical. But it is not comical, but tremendously interesting. It is one of the most fascinating things in the insect world. And that is saying a lot,” he would write.

Bibliography

HEIDBORN, T. (2010) “Dancing with bees”. Max Planck Research

KEARNEY, M. (2016): “Bees, Nazis and the Nobel prize: the amazing life of Karl von Frisch”. The Spectator

PAULSON, S. (2018): “Waggle Dancing with Karl von Frisch”. Other Knowledge

Michael Jackson (1967): “A biologist remembers”. Press release

Michael Jackson (1973): “Decoding the language of the bee”. Nobel Lecture

WINSTON, M. L. (2016): “Ethology: Intrepid translator of the hive.” Nature