Cavendish, genius in solitude

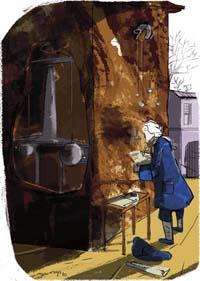

By the time the server read the notice of what he wanted to eat, the head of the house looked from his telescope. Placing the telescope in a hole in the wall, he looked at a gadget across the wall. In the center of this gadget were hanging two balls of 140 kg of lead and two small balls next to them. The objective was to observe the force of gravity between them. In the words of his boss, he "weighed the world."

It was the spring of 1798, Henry Cavendish was 67 years old. There, in his house, apart from the world, he felt comfortable. He did not like relationships. It also communicated in writing with the servers, which were prohibited in the presence of Cavendish, as otherwise they would be dismissed. And to avoid crossing with anyone, he made a home entrance to use it alone.

He once opened the door and met an Austrian admirer. The Austrian began to praise, but soon saw Cavendish running away leaving the door of his house open.

However, in some exceptions Cavendish was concentrated in public. Occasionally he attended scientific meetings organized by naturalist Joseph Banks. Nor was the weekly dinners of the Royal Society Club lacking.

But in those meetings and dinners his thin voice could rarely be heard. The rest knew that in no case should they look or speak directly. If someone wanted to talk to him, he had to put himself at a reasonable distance and do it as if he were mistaken in the vacuum. If said was scientifically worthy, perhaps Cavendish would respond.

He once dined with astronomer William Herschel. Herschel's new telescopes and observations were from word to mouth. As dinner progressed, Cavendish, who had been mute until then, suddenly said: "I have heard that you have seen the round stars." And Herschel: "As rounded as a button." Cavendish remained silent until the end of the dinner and then asked again: "As rounded as a button? ". "Yes, as rounded as a button." It was the whole interview that night.

According to Oliver Sacks, it was an autistic genius that George Wilson, Cavendish biographer, describes as follows: "He did not love, nor hate; he had no hope, nor fear... Apparently, it was a machine to calculate his head; his eyes were a merely visual tool, not a source of tears; his hands a tool of manipulation, which never vibrated emotionally, and never gathered to worship, thank or despair; his heart was but an anatomical organ necessary for the circulation of blood. ...He felt that a deep abyss separated him from others and no one, neither he nor the others, could cross that abyss... In this way, he dismissed himself, took leave of the world and became a scientific anaceta and, like the ancient monks, was imprisoned."

In his "prison" he had everything he needed. Being one of the most prosperous families of the English nobility, he did not lack money, and if otherwise he had paid no attention to money, it served to turn his house into a large laboratory and move on to investigate life.

And for Cavendish the world was full of things that could be counted, measured and weighed. His vocation was to measure and experience, and his obsession was precision. Even when he could not make measurements accurately, he tried to make the best possible approximations. For example, since there was no ammeter, it was used to measure the intensity of the electric current. He took downloads and pointed to the intensity he felt. These discharges grew to almost lose consciousness.

His gas works were famous. Among other things, he was the first to isolate hydrogen and discovered that by burning it water was produced, that is, the union of hydrogen and oxygen allowed to create water. Water, therefore, was not an element.

However, many of his works did not publish them or tell anyone. All he cared about was to know, to show that he did not know. When physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1874 had the opportunity to read unpublished writings of Cavendish, he went crazy. Many of the discoveries made in recent years were made by Cavendish almost a century before: energy conservation law, Ohm law, Coulomb law, Dalton partial pressure law, Charles gas law, etc.

But Cavendish's best-known experiment is to "weigh" the world. The idea was not his, but of the priest John Michell. Michell was also one of the clearest heads of the time. In fact, musician Herschel came to him to learn how to make telescopes, when he decided that what really interested him was astronomy.

The most perfect thing Michelle had ever designed and built was never that Earth weighing machine. Unfortunately he died before he could perform the experiment. And the machine came into the hands of his friend Cavendish.

Cavendish, as always, wanted to make the measurements as accurately as possible. He thought that changing the temperature of the room in which the machine was located or the lower drafts could drastically change the results. So he put the machine in a cell and set it up to handle it from the outside.

It was not easy, he had to make eleven measurements for almost a year. But finally, in an article from 1798, he issued 29 measurements of Earth's density, the average of which indicated that it was 5.48 higher than water. Surprisingly, the last average was wrong and, in fact, 5,448 correspond to these measures. This value is less than 1.3% of the currently allowed. It was not far away.

In recent years the main topic of research was astronomy. In 1809 he published his last article on some astronomy instruments. The following year he died as he lived in February 1810, only in his "prison".