From the laboratory to the clinic

From the working table to the head of the bed (from bench to bedside), this is how we know the research directed directly to the therapy, which is being carried out in various laboratories that investigate the treatment of cancer worldwide. José Antonio Rodriguez worked in one of these laboratories until four years ago and, in his opinion, "is a very interesting concept".

José Antonio Rodríguez is now professor of the Genetics Department of the UPV. He spent three years earlier in Australia and seven in the Netherlands in cancer research: "In the Netherlands I worked in a hospital, not at university. He worked in the department of Medical Oncology and there they have two lines: in one of them they treat patients and in the other they study the mechanisms of drugs in tumor cells that are maintained in the preparations of growth. I worked in that second, because I am a biologist, not a doctor, but the two lines are closely related."

According to Rodríguez, this way of working is appropriate for biological therapies. "In chemotherapy, for example, researchers try to know which is the maximum dose they can give and then give patients a lower dose. Biological therapies, for their part, are less toxic and in them many times there are no maximum doses. Its effectiveness should be tested differently. It is about measuring biological markers (for example, the concentration of a protein) and seeing if the drug interferes with cell signaling that we want to prevent."

The blockade of these paths is the basis on which many of the therapies are being tested: the identification of the mechanisms or trails necessary for the growth, reproduction and diffusion of tumor cells and their obstruction by means of molecules developed in the laboratory. According to Rodríguez, these trails are also used by conventional cells, but they do not use only one, but four or five, to do the same. On the contrary, tumor cells have an overactivation in one of them and others do not use them because they do not need them. "This overactivation path brings advantage to the cell but also a weak point at the same time (Achilles Heel). If we block this path that gives them advantage, the cell dies."

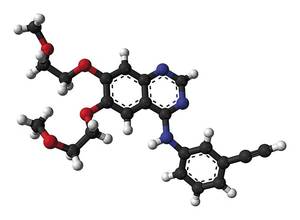

In the Rodríguez section, for example, they investigated EGFRa inhibitors. EGFR is a receptor located on the cell surface (epidermal growth factor receptor) that controls that the gene that controls it is mutated or that its expression is excessive can cause cancer. "Blockade of EGFR signaling prevents the development of cancer. As the inhibitors tested by us are already used in patients. One of them is erlotinib, used in hospitals to treat lung cancers." Anti-COVs, erlotinib itself or other inhibitors are also being tested in the brain, colon and other types of cancer, depending on the mechanism of each type of tumor.

Keep in mind that there are many types of cancer. "Many say that each patient has one type of cancer, his own," says Rodríguez. Therefore, researchers should look for the most appropriate inhibitors of all cancers. To do this, it is necessary to analyze the genetic defects (mutations) that have caused the tumor.

The war on resistance

In any case, Rodríguez warns that this strategy has a limit: "The problem is that they develop resistance to inhibitors."

Over time, when we inhibit a path, tumor cells begin to use other paths that serve to do the same and become resistant to the inhibitor. Therefore, they must be administered in a combined manner.

In Rodríguez's words, "this is a war, and when a road closes we must try for another." In addition to the pathway of the inhibitors of the paths, it is also important that of monoclonal antibodies. It includes, for example, trastuzumab (Herceptin), antibody against a receptor similar to EGFR. Trastuzumab is commonly used against breast cancer and is now also testing other types of cancer in clinical trials.

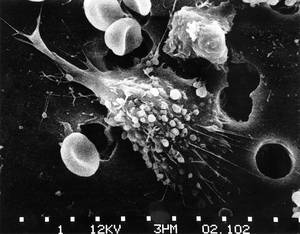

These antibodies are generated in the laboratory and are able to bind specifically to a specific antigen. Monoclonal antibodies have long been used in the diagnosis of cancer. As a therapy, researchers try to identify on the surface of tumor cells the growth-related antigens (e.g. receptors of growth factors) and design the antibodies associated with them. In this way, antibodies bind to antigens and cells cannot grow.

Monoclonal antibodies designed specifically for the promotion of the immune system are also used.

Vaccines against cancer

In relation to the immune system, another pathway that is being investigated to fight cancer is vaccination.

Vaccines used in infectious diseases are administered before the onset of the disease. These vaccines contain fragments of infective agent antigens or deactivated by the same agent and aim to prepare the immune system when the agent enters the body. Somehow, the vaccines teach him who is the aggressor, which allows the body to prepare the best weapons against him.

Cancer vaccines, however, would be used after the onset of the disease to treat or prevent its spread. One of them is being tested at the Clínica Universidad de Navarra. The goal of the vaccine is to avoid the appearance of breast cancer after being treated and for this purpose dendritic cells of the woman (cells of the immune system) are used, which are stimulated with tumor cells of the patient. Thus they teach dendritic cells what is the aggressor.

Marta Santisteban, head of research, said she is being tested with a subgroup of breast cancer patients and will know if it is effective in May 2012. In any case, it would complement conventional oncological therapy and not surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

In addition to the fight against breast cancer, vaccinations are also being tested for other cancers in other cultures such as prostate, kidney, ovary, colon...

However, Rodríguez considers that although vaccines are shown to be effective, it will be difficult for the molecule to become inhibitor and conventional. "The question is that they are autologous, that is, they are made with cells of the patient himself. Therefore, each one has to do his own, and that is not available to everyone, because it is very expensive."

Virus, Trojan horse

Another strategy that is giving good results is that of viruses. Rodríguez explains what it consists of: "They try to transform the genome of viruses so that they can destroy tumor cells without destroying normal cells. Oncolytic viruses are common. These viruses have been modified by the genes so that they can only enter tumor cells. When entering a tumor cell, the viruses only divide them over and over again until the cell explodes."

On other occasions, a gene coding a toxic is introduced. "In this way, once introduced into the cell, they produce the toxic and actively kill the cell. Armed viruses". The armed viruses.

Oncolytic and armed viruses are examples of gene therapy and their research and clinical trials are quite advanced. Others that are being tested in the gene therapy bar are in later stages. Among them are the substitution trials of mutated genes in cells by healthy genes. Other laboratories include specific genes in tumor cells to be more sensitive to radiation therapy and chemotherapy. There are also those who try to introduce genes that prevent angiogenesis, with which tumors cannot produce and spread blood vessels.

There are many ways researchers are testing. Some are still in experimental phase, but others are already very advanced and have been authorized for use. There are more and more opportunities that open the way to hope.