Smoke market

The carbon dioxide emission rights (CO 2) market was launched in Europe in 2005, being the most important market of this type currently existing in the world. Precisely within the European Union's environmental policy, carbon dioxide emissions trading is the essential instrument for achieving the objectives set by the Kyoto Protocol.

In fact, the idea is not new. For example, with the aim of reducing acid rain, in 1990 a similar market was created in the United States for trading sulfur dioxide emission rights. However, the aim of the European market is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, the tonne of CO 2 emitted has been valued and the market is based on the trading of emission rights of this gas.

And that is precisely one of the criticisms they make, that is, that only carbon dioxide takes into account. However, as of 2013, the European Commission plans to market other gases, such as nitrous oxide and perfluorocarbons, as well as other sectors currently outside this market.

At present, the spills of companies in the electric sector, oil refining, steel, cement, lime, tiles and bricks, tiles and tiles, glass, frits and paper, paper and cardboard paste are considered. Among them, they generate half of the carbon dioxide emitted in Europe. A lot.

But transport also generates a large amount of carbon dioxide, approximately 20%, and the proportion increases year after year. However, this 20% comes from low-emission individuals and the rights trading system does not control this type of dumping. The exception is the dumping of aircraft, and that is, since 2012 the European Commission intends to take into account the emissions of commercial aircraft passing through European airports.

Sale and purchase

Thus, the emission trading market is based on carbon dioxide emitted by some sectors. In addition to the 27 countries of the European Union, since last year Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein also participate, affecting a total of 11,000 companies. The participation of companies is not voluntary, they are obligated.

Environmental economist Patxi Gre has explained how it works: "Each company has emission rights that the European Commission has granted it. If it manages to issue less than expected, it will have plenty of rights that can be sold to a shipper more than expected."

That said, it seems simple, but Gre himself has mentioned some of his difficulties. One of them is the determination of the emission rights of each company, that is, the location of the limit. In fact, the market is developing in three phases, the first, between 2005-2007, was for testing, and then they realized that there was an excessive distribution of rights. "Companies had surplus and the price of rights declined enormously."

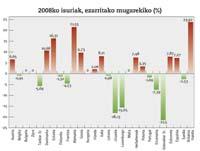

In fact, to determine the amount of emission allowances to be granted to each company were based on the historical discharges of the companies, although in a second phase (2008-2012), due to the existence of errors, there have been closer limits to the companies. In particular, companies have distributed 6.5% less dumping rights than in 2005. It is expected that the market will work and that it will finally contribute to achieving the objectives set out in the Kyoto Protocol, since from 2013 the number of rights will decrease by 1.74% year after year.

However, for Gre, instead of distributing the spill rights, the logic would be to auction. The most willing to pay for them would benefit from the rights. "But the European Commission needed companies to be in favour of the system and companies argued that the acquisition of emission rights could result in a loss of international competitiveness." Therefore, they decided to grant rights, although over time the commission intends to reduce gratuitousness.

In theory, according to the European Commission, the emission rights for 2024 must be auctioned. However, the Commission itself considers that "there may be exceptions to high-energy sectors" if the auction system hurts to compete internationally.

Waste reduction

Either way, Gre believes the system is cost-effective. In his opinion, "it helps reduce spills in cases where it costs less to reduce." In fact, if the reduction of spills is less than the spill, the company invests in reducing spills. By issuing less than before, it can sell emission allowances, thus obtaining benefits." The system therefore facilitates investment in emission reduction mechanisms.

According to the Commission, the market is being efficient, as the industry has reduced its emissions by 6% in the last year. But not everything has been thanks to the market. Gre warns that the crisis has also influenced this. "Companies have reduced their activity and have been a way to finance the sale of emission rights. However, this has meant a significant reduction in the price of dumping duties." In addition, "it must be taken into account that oil has been reduced and that companies have replaced coal with this fuel. Oil generates less carbon dioxide than coal, which has also contributed to reducing emissions."

However, the market is underway and has consequences on companies. In fact, once the year is over, companies must return the duties corresponding to the tonnes of CO 2 issued. The rights they have not used have the possibility of selling or conserving them for the future.

If a company does not return the rights it had to return according to what it has spilled, it receives a penalty. The following year you must acquire the necessary rights to compensate for this fault or deficit, indicating the name of the company in the list of offenders and paying a fine for each ton of CO 2 poured above the limit. The initial fine was 40 euros per ton, but is currently 100 euros.

For example, the Navarra company El ctrica de la Ribera del Ebro, with 1.143.212 tons of CO 2 in 2008, has returned the corresponding to 309.394 tons. Consequently, the European Commission will be sanctioned. In similar conditions are other companies, almost all of them in the electric sector.

Bag, stage

Patxi Gre works at NAIDER, offering consulting services to companies and administration, among others. According to him, many companies in the area "have not yet internalized that emission rights are an asset, which in the end is money". Therefore, Gre confirms that consulting services have a large margin of growth.

Factor CO 2. They are specialized in climate change and have a subsidiary dedicated to the carbon dioxide emission rights market, Factor CO 2 Trading. Director Kepa Solaun agrees with Gre's statement, but only in part. In his opinion, although in the first phase it was, from 2008, and coinciding with the crisis, companies have begun to play "strategically".

Solaun has provided us with data: In 2007, around EUR 40 billion and EUR 90 billion moved into the emission rights market, 130% more. In addition, with respect to the previous phase, the movements are "larger and more complex". Looking ahead, it is optimistic, since "companies operate more and more, expect a price increase and from 2012 there will be more companies participating".

It seems that there is the possibility of selling smoke business. Of course, far remains the slogan who pollutes pays.