A new look at the eye

Today, archaeologists still struggle to accurately date certain remains of rock art, but it was even more difficult before. For archaeologists, however, it is necessary to have a chronological classification system of the paintings, and more than one attempted to create a classification. Among these classifications, the most complete and accepted was that of the French archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan.

Leroi-Gourhan, an archaeologist of great experience and prestige, built in the 1960s a chronological system of classification of rock art based on its objective data and hypotheses. The system was widely recognized and for many years most archaeologists have valued it positively.

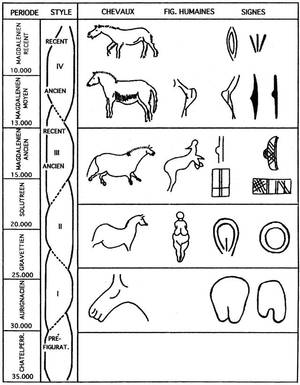

According to Leroi-Gourhan, four styles can be distinguished over time. He called the oldest style I, that of Aurignacaldi (B.C.) 30.000-27,000), and IV. style to the most recent, to the last Magdalenian (a.C. 13.000-9.000). Section II. and III. defined styles and proposed a continuous evolution from I to IV. Thus, the I-style drawings were rough, simple, and at the other end were IV. much more complex and developed style than the old ones, very close to reality.

Although this classification is still used, lately many experts are very critical of it. For example, archaeologists Diego Garate and Joseba Ríos are clear that the classification of Leroi-Gourhan is wrong, according to them, "current dating techniques have revealed that the classification of Leroi is incorrect."

However, for Garate and Ríos, it is not surprising that the chronological classification of Leroi-Gourhan is successful and valid until recently. "It must be taken into account when they began to discover and investigate rock art [XIX. At the end of the 20th century], Darwinism was in full swing. They believed that man evolved from cave times: the Neanderthal would be a wild being and modern, civilized man. And that mentality was applied directly to art, without contrasting anything," explains Garate.

He also recalled the influence of social evolutionism: "It was the epoch of imperialism and colonialism, and they compared rock art with that of primitive peoples and seemed to them to be similar, so it was logical to think that art developed over time."

Moreover, at first many did not admit that rock art was so old: "It seemed impossible for the Palaeolithic men to be able to make such realistic figures. Note: the first drawings that were found, in 1879, were by Altamira and, as is known, are magnificent. In addition, where to find it and in Spain. For the French it was very difficult to accept all this."

However, in the following years other examples were found, even in France, which managed to demonstrate that rock art was Palaeolithic. Once this was accepted, the paintings were classified chronologically according to the evolutionist mentality. "That in those times the proposal seems reasonable, however, does not mean that it was correct. For example, the art of Greek civilization was very worked and then also the Roman, but then came a time when art was not as developed as in previous centuries. Therefore, evolution doesn't always improve and it doesn't have to be that way," explains Ríos.

Garate believes that what is considered developed must also be taken into account: "And the more realistic the paintings, Leroi-Gourhan considered them better or more developed, but that is a conviction, it cannot be said."

Chauvet against the paradigm

Analyzing the classification of Leroi-Gourhan, both Garate and Ríos have detected numerous errors: "He considered that works of art had common characteristics that he included within the same style and that those that did not conform to his theory discarded them. However, since they began using the Carbon-14 test, the Leroi-Gourhan classification was wrong."

Garate (cave of southern France in the department of Ardèche) has set an example of the cave of Chauvet: "Dating has shown that Chauvet's rock art belongs to Aurignacaldi, the oldest time. And what art does Chauvet have? Well amazing, quality and rich. There are very worked and realistic images, made with different techniques. Some are painted in red, others in black or ochre; there are figures of hands, obtained with blown paint; marks made; engravings and with the song highlighted...".

Rio sums up: "From a technical, compositional, thematic, aesthetic, perspective point of view... it is very complex and worked in all aspects. And we know that about 30,000 years ago. And this is totally contradictory with the classification of Leroi-Gourhan, according to which the art of that time was very basic, rough and uncultured, so the images of Chauvet IV. should be of style, of the last of the Palaeolithic, that is, of the Magdalenian".

This contradiction provoked controversy for breaking the existing paradigm. "Some opted for Leroi-Gourhan's scheme and claimed that, for example, the ancient coal used to make black paintings, that of Aurignacaldi, and the authors of the paintings, that of Madeleinealdi. However, all available evidence makes it clear that the paintings are by Aurignacaldi, which were made at that time. However, it is normal for these resistances to appear when a paradigm is broken."

For Rios, Chauvet's example is suitable to explain the evolution of the history of rock art, since "it shows very well how a theory was built to explain what until then they knew and how the theory changes thanks to the tests obtained through techniques".

In addition to rock art, Garate believes it serves to know the societies of the time: "Keep in mind that the men who made Chauvet's paintings were the first Homo sapiens to reach that part of Europe, and in the paintings it is clear that this type of art was totally dominated. From there, in 20,000 years, they do not invent anything: styles change a little, themes also, but they use the same techniques and, in essence, it is very homogeneous."

Puzzle Pieces

Chauvet is no exception and other European caves have found clear examples that do not correspond to the chronology of Leroi-Gourhan styles. Therefore, in recent years it has become clear that the style criterion does not serve to make a chronological classification.

However, in some cases, comparing styles can help when it is not possible to specify much in dating. Rios gives an example of rhinos: "In Aldène, a cave in the Massif Central of France, there are rhinos very similar to those of Chauvet. Chauvet's are dated, but in Aldène the exact date has not yet been reached. Thus, since there is no other evidence, the observation of the style can be complementary, and in this case it is observed that, by the way of making the ear of the rhinoceros and other conventions, it is very likely that the paintings of both caves are of the same time, since the rhinoceroses are very similar".

According to Garate, "this is like a puzzle. We have some pieces, some of them are dated and others are more or less their accessories, but the more pieces we get and date better, the better we will know better the image we were forming correctly or the pieces that are going to be put differently."

The last piece they have found is in France, in Castanet (Dordogne). Using carbon-14 and other advanced techniques, Castanet's images have shown that they are about 37,000 years old, that is, they are one of the oldest that have been found so far. "And they claim that those who did these first works had long dominated the techniques of creation, which were widespread in Europe and that there was a great variety of styles and techniques," Garate warned.

"In addition, this demonstrates the complexity of the societies of the time," added Ríos. "In fact, in the early days of the Palaeolithic, in Aurignacaldia itself, it is observed that human groups were already separated and each had their art and way of life."

For Garate and Rios, this is important because before there was a widespread evolutionary mentality and, like the vision of the art of Leroi-Gourhan, they believed that there was an evolution in the development of society. This vision has changed radically by demonstrating that the early Palaeolithic societies were as complex as the later ones. "Yes, it is very interesting to see that the Neanderthals did not create art," said Ríos. "In the deposits, from a certain period there is an explosion of artistic expression, but always associated with Homo sapiens".