And the day became night... wonderful?

Dragon that eats the sun

Since ancient times, human beings are attentive to what happens in the sky, moved by practical objectives: if it rains, if we can use the solar rays to heat something... and, undoubtedly, astronomical phenomena have also been the object of our attention. Eclipses are the main celestial events that caused the terror of primitive civilizations, among which is the greatest emotion of total sun eclipses, so it is understandable the passion to record and predict these phenomena.

For example, the Chinese believed that a dragon tried to eat the Sun during solar eclipses and believed that to scare the dragon it was necessary to play the drum, scream and shoot arrows to the sky. That is why the story of the astronomers of the Chinese emperor Hsi and Ho is known. It seems that the two astronomers spent too much time drinking, rather than recording what was happening in the sky, and that a solar eclipse occurred without any observation. As a result of this error, the emperor made the decision to cut the astronomers' heads.

The eclipse we mentioned in the introduction also had an important, political consequence in this case. This solar eclipse put an end to the war that was taking place in Asia Minor, on the Anatolian peninsula, since both the Babylonians and the Greeks, like the Chinese, said that the disappearance of the sun was a bad sign. This is what Herodotus tells us:

“(...) and among the medians there was a five-year war in which, often, the doctors beat the Lydiks and often the Lydicos, and also the Lydicos, who did some night fight. And with the war equalled, the sixth year of conflict turned the day into a full struggle. This is the evolution of the day that the Thales Miletus had previously announced to the Ionian, establishing the anniversary of the conflict. But the lydarras and the midwayers, when they saw the day as night, tried to break the conflict and make peace between them.”

The Greek historian warns us that, in addition to signing peace, they also made the contrast and other rites, the fear of the eclipse that was so great:

“In fact, these peoples, in addition to making the typical Hellenic oaths, make an incision in the arm and trace the blood between them” (Herodotus, Stories, I.74)

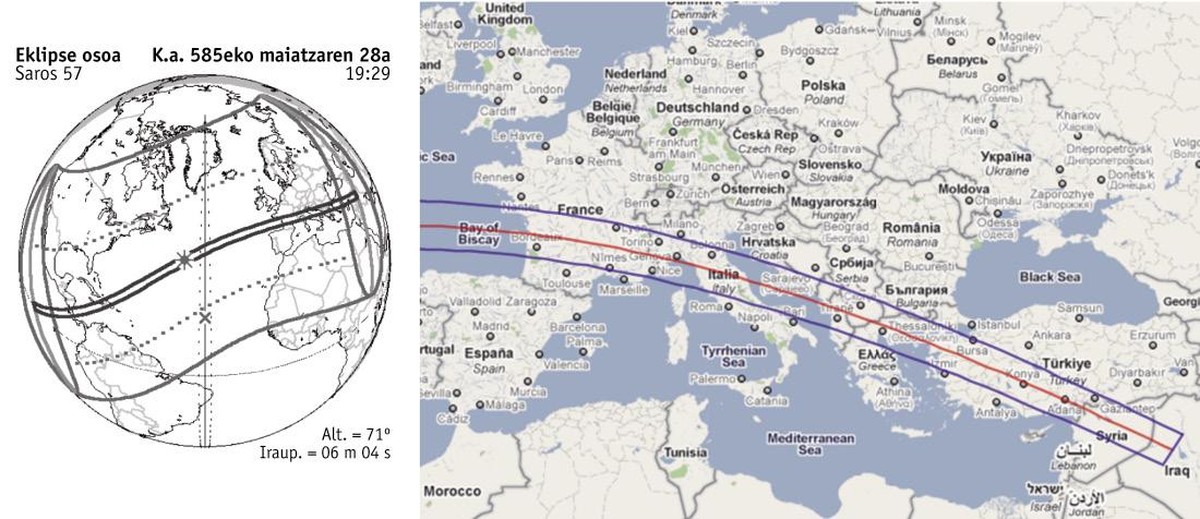

Today we know if that eclipse went to. C. It happened on May 28, 555. The eclipse crossed the peninsula of Anatolia and the total eclipse could be seen in the afternoon on the bank of the river Halys (colony), after three minutes of total coverage of the Sun and giving way to the crown and the starry night. Therefore, taking into account the superstitions of the time, it is possible that the disappearance of the Sun in the midst of war has caused peace between both sides, as Herodotus tells us.

However, Herodotus adds something else: Tales announced an eclipse “with the anniversary of the conflict.” To begin with, the phrase is a bit rare because when predicting an eclipse we can also know the exact day; in fact, it does not make much sense to predict the year in which the eclipse will occur. However, it is important to note that Herodotus announced the event one hundred years after the eclipse occurred, so it is not surprising a certain transformation of the details in the communication process. However, most historians have positively valued Herodotus' phrase and many books and articles collect that Tales Miletus announced the solar eclipse phenomenon.

Thales, philosopher and scientist

Thales was a curious character. Known as a philosopher, it is classified into the presocratic group, giving way to rational thought in the sixth century BC. Such influenced the importance of water, defining>{> (arkhe) or as a principle, and proposed that the world was a disk full of water. It seems that Tales was also a little clueless and, they say, on a starry night he fell into a well looking up at the sky and provoked the laughter of others.

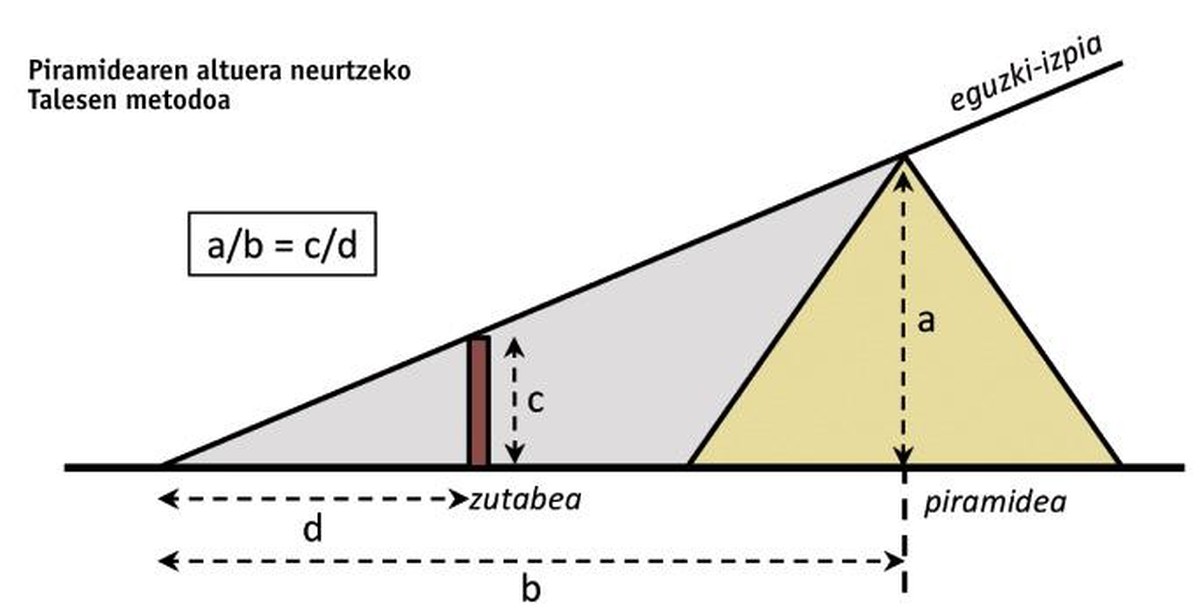

Thales was one of the seven sages of Helad. In addition to participating in the early philosophical speculations, he made some spectacular achievements. The best known and most important is probably the one made during the trip to Egypt, where he managed to calculate the height of the pyramids, measuring the length of their shadows. The idea is quite simple, based on the concept of proportion: when the solar rays arrive parallel to the earth's surface, the proportion between the shadows of two vertical objects will be the same as that of the heights between objects. Therefore, being known the height of a reference stick or column and the length of its shadow, we only need to measure the length of the shadow of a pyramid to calculate the height of the pyramid. At present, this concept of geometry is called “Theorema de Tales”.

During his trip to Egypt, Thales also crossed Babylon and made a certain exchange of knowledge with his people. And that brings us back to our famous eclipse. We do not know exactly what Thales learned from the astronomers of Babylon, but it is true that they had a deep knowledge of eclipses. For example, at that time the Babylonians were able, thanks to cycles, to predict lunar eclipses and to have an accurate record of the eclipses observed from it for at least five centuries. Thus, in the contemporary era, Tales' prediction has been: He learned in Babylon how to calculate eclipses and, using this knowledge, successfully announced the spectacular phenomenon of 555.

But let us not forget that the eclipse that ended the war was a solar eclipse and not an eclipse of the moon. Most contemporary historians have not taken this detail into account, but astronomically it is not the same. And it seems that C. in the sixth century the Babylonians were not yet able to predict solar eclipses. However, as will be explained, due to the characteristics of the eclipse, Tales in no case could predict the disappearance of the sun in the Halys River or apply Babylonian knowledge.

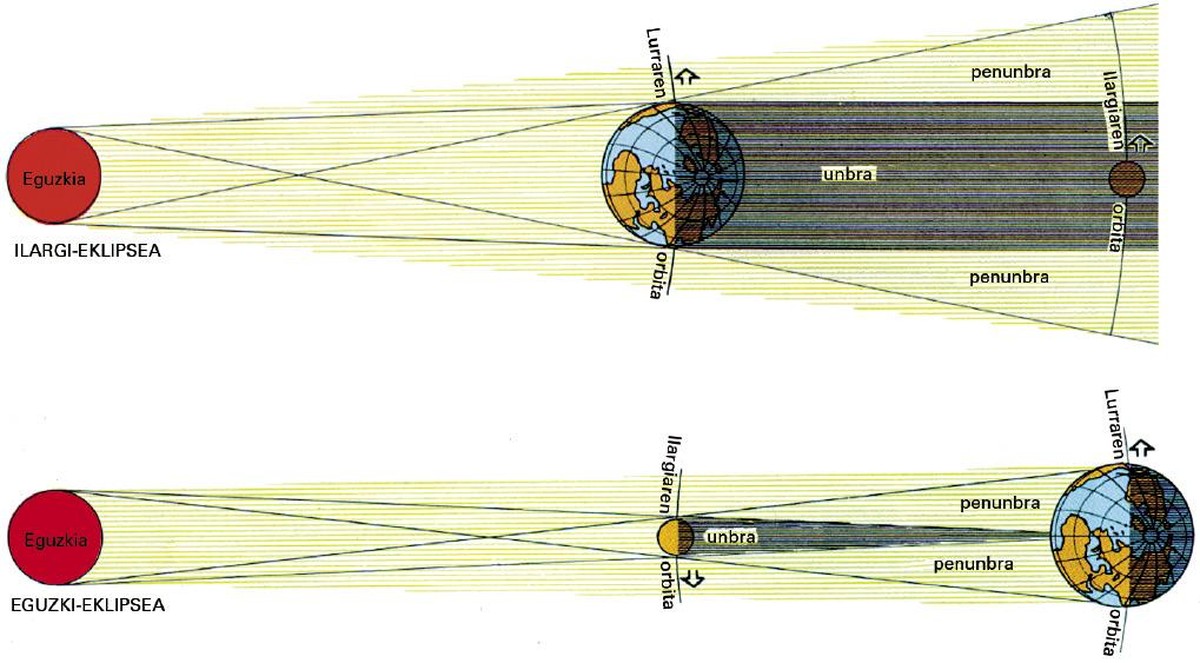

Cosmic shadows

Let's take a leap and try to understand, from the current point of view, when and how eclipses occur. The Earth rotates every year around the Sun and the Moon around the Earth once a month. These movements can cause the Moon to pass through the shadow of the Earth and an eclipse of the Moon to occur; the shadow of the Moon may also touch the earth's crust, cover the Sun from our point of view, and a solar eclipse will occur. Therefore, if the orbits of the Earth and the Moon were located on the same plane, the eclipses of the Moon should occur monthly (when the Moon is full) and the same with the eclipses of the Sun (an eclipse every month). However, the orbits are not exactly in the same plane, since the difference between the two is about 5 °, so eclipses are less noticeable. In the eclipses of the Sun, in addition, the shadow projected by the Moon is so narrow that it is only visible in a small area of the Earth's surface, in a band of about 100-200 km wide.

Due to the tilt between the above-mentioned orbits and the Earth's motion around the Sun, eclipses are only possible twice a year in times known as eclipse seasons. For example, eclipses could only occur in the years 2014, April and October; the following year, in the months of March and September 2015, eclipse stations will occur (year after year, these stations are gradually being advanced due to the slowness in relative orientations of orbits). Therefore, before the observation and recording of eclipses sufficiently extensive, it is not difficult to conclude that these have only occurred in the seasons of eclipses; moreover, knowing that eclipses occur systematically in Full Moon or New Moon, eclipses will only be possible in a few days of the year.

These eclipse seasons were well known by the Babylonians and probably by Thales. But with them we can only predict the probability of an eclipse occurring. In Moon eclipses it is not surprising that this “blind” prediction gives the prediction of an eclipse visible from the entire Earth area in which it is night. In the case of Sun eclipses, however, it is more difficult to match that blind prediction, and turning day into night would be really wonderful, because the probability is up to a thousand!

However, there are methods of forecasting solar eclipses and accurate prediction of lunar eclipses. At present, we calculate eclipses with computers, that is, using orbital elements. But the Babylonians, and other civilizations, identified cycles of repetition; the best known is Saros: After 18 years, 10 days and 8 hours an eclipse of very similar characteristics occurs.

However, this cycle is not so useful to predict sun eclipses, because due to the 8 hour difference the eclipse will be geographically displaced about 120º: The pre-eclipse of Thales, for example in the Saros cycle, was visible in the center of the Atlantic Ocean. The repetition cycle known as triple Saros or Exeligmos is much more useful: As these 8 hours accumulate, this third eclipse occurs practically in the same position, 54 years later.

Thales and eclipse

As a result, some authors have proposed that Tales could use the Exeligmos cycle. It is possible that the eclipse, which occurred 54 years earlier, was discovered listening to the people of Miletus or reading in the records of Babylon and taking advantage of this fact, the cycle Exeligmos was used to predict the total eclipse. But, once again, this hypothesis has a big drawback: From the point of view of Asia Minor, we can say that the eclipse of 575 is an exception, since in it was located the end of the route of the total eclipse. The eclipse that occurs after the Exeligmos cycle geographically describes the same path, but there is a small gap that causes the displacement of the eclipse to the eclipse. Taking this into account, it can be calculated that it is impossible to see the pre-cycle eclipse from the Miletus area, so in this particular case Tales could not apply this cycle.

Therefore, our philosopher could not use the cyclical method to predict the eclipse, as has often been argued, because previous eclipses were not visible from that region of the Earth. Or rather, by the special characteristics of the eclipse seen from Asia Minor in 5805, Tales could not be, by a cyclical method, the security of a total eclipse of the Sun. That means that if we knew that Tales used one of those cycles, we should understand that he invented the announcement of luck (the Ionian philosopher who was very lucky! ), and we should not consider it a scientific method.

However, let us remember that one hundred years after that historical event Herodotus made it known, and it is possible that during the oral transmission process the information has been modified. For example, it is possible that at that time Thales accurately announced some moon eclipses, with cyclical repetitions, learning from the Babylonians or deduced by the philosopher himself. Moreover, as has already been indicated, if Tales probably knew that eclipses of the moon and sun can only occur at certain times of the year, it is no wonder that Tales warned the Libyan authorities that it was the season of the eclipse. Someone knows in the middle of the fight, when the day became night, someone remembered the words of Thales and the eclipse that put an end to that long war gave Thales the fame of always.