The Moon, a forgotten dream

The Moon, our satellite, has always had a special attraction in human beings. Curiosity about the Moon and its special symbolism have been at the roots of most human cultures. And, of course, the dream of many ideas to reach the Moon. For example, the satirical Greek writer Luciano de Samosa took the journey to the Moon a century and a half after the death of Christ, in his work Real History.

Political objective

Until the launch of the first Sputnika, human ilargination was a chimera. From then on it was seen as a serious and close option, and the two competing powers for space set as their primary goal to bring a compatriot to the Moon. Like all the space exploration of the time, the conquest of the Moon was put at the service of political objectives. The Apollo of the USA is the most representative testimony of this program.

Apollo Program, John F. from USA. President Kennedy was born as a promoter in May 1961. The goal was to pose a guided ship on the Moon before the end of the decade (“before this decade is out”, according to Kennedy). There was no deep scientific reason behind the momentum of the Apollo program. Political reasons prevailed. The American intention was to demonstrate, through a great technological advance, that his political system was better than the Soviet. In the years prior to the decision the Soviets left Americans in the field of space exploration behind on more than one occasion: launching the first satellite, placing the first man in space and taking out the first hidden photos of the area of light, among other things. There was prestige at stake.

The Apollo program was very expensive. From 1961 to l972 NASA allocated 25 billion dollars to the development of the program, which represents approximately 60% of its budget. However, this amount represents only 1.5% of the money that the US administration has spent in the same period, little considering that military spending was 42%. The Apolo project involved 250,000 people from 10,000 different companies. The amount used was huge, but according to calculations, the US government recovered seven dollars for every dollar invested thanks to the technology developed by the program.

Apollo 11

On July 16, 1969, there was a regular movement in and around the Kennedy Space Center. So many people never met. More than a million people concentrated on the roads and highways leading to Cape Canaveral. The beach, campsites and rest areas were full of shops, caravans and motorhomes. The airports could not cope with the large traffic of planes that were arriving.

The NASA press office accredited 3,000 journalists from 56 countries worldwide. The eyes of the entire planet were oriented towards the bright perpendicular metal tower in the center of the launch port. Television images attracted 500 million people and 1 billion eyes. In the US, for a few hours, crime and evil remained at the lowest point ever reached. US TV device vendors had a pagotx, sold as churros before day E.

Those looking at Apollo 11 at the end of Saturn V seemed like an endless countdown. The U moment seemed to never come. Or less sixty seconds: green light for launch. Just a minute. Or less twelve seconds: The metal arms that hold the Saturn V begin to open and the ignistic sequence begins.

U minus 8.9 seconds: the first flames have been seen, but as the rocket is still firmly attached to the ground, it stands firm accumulating power. Three, two, forward, zero.

At this moment, the last supports that support the rocket have been detached at the same time and between the fumes and fires a metal wedge of 100 m of length has begun to move away from the ground.

Neil A in the cabin of Apollo 11, inside the space garments. Armstrong, Edwin E. Astronauts Aldrin and Michael Collins barely realize what is happening outside. The pressure pressing against the seats indicates that they are leaving the Earth. However, the cries of joy and the carouses of thousands of people who are seeing the sound of smoke and fire surrounding the rocket and launch do not reach the inside of the cabin.

It was 9.32 hours on July 17, 1969. The launcher's first two steps gave a speed of 28,000 km/h to Apollo 11 and took him to the Earth's orbit. After two laps around our planet, two hours and three quarters later, the third step placed the boat on its route to the Moon at a speed of 39,000 km/h.

The third step remained on for 5 minutes and 47 seconds. When the impulse given by the engines expired and ceased, the gravitational force of the Earth began to pull the boat, slowing its speed. When the speed of Apollo 11 reached 3,200 km/h, the gravity of the Moon began to work by pulling and accelerating the ship. At 72 hours of thaw, the ship began orbiting the Moon at a speed of 8,400 km/h.

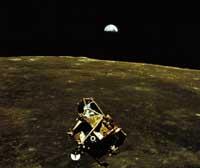

On the Moon

On the fourth day of the mission, when the ship was to start the seventh lunar orbit, the tension of the crew began to rise. It took less than half a day to start the separation maneuver between the control module and the moon module. Take the moon in fifteen hours.

The spacecraft entered the liver of the Moon and radiocontact with the Houston control center again interrupted. Aldrin accessed the moon module with narration. She was baptized as Eagle. After lighting the main control panels, Columbia returned to the control module and placed the moon suit with Armstrong.

The separation maneuver began in the second orbit. The two astronauts passed to Eagle and the port communicating the modules was closed. As previously calculated, controlled rocket explosions separated the lunar module from Columbia. With a slow jump the lunar module began to move away in the lunar void. In Houston they were worried and asked Collins for the maneuver, who had remained in the command module. “The eagle has wings.”

Still, Eaglea was 90 km from the surface of the Moon and a few meters from Columbia and had to start three complicated maneuvers before settling in the Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tranquillity).

First, Collins kept the control module rocket on for a few seconds so that during the successive maneuvers the two modules were far enough away.

Eagle's posing could not be subject to automatic driving control alone. The computer controlled variables in rapid change (altitude, speed and fuel consumption). The initial steps were guided by the computer, but when 750 m were missing, Armstrong took manual control of the ringing maneuver.

It took twelve minutes to sit on the ground and the ship was 75,000 m from the surface, approaching a speed of 4,500 km/h. Armstrong noticed the problems: they were falling at a speed of 22 km/h higher than the estimated and would not settle at the planned point. If the speed was higher than 12 km/h, the mole should be cancelled. Houston promised to move on.

Suddenly, the boat's computer rang the alarm call: 1202 alarm message. The working capacity of the computer was exceeded. No wonder. The association radar was on and at the same time tried to locate the resting place and calculate the return route to Columbia. The control ordered not to attend to the alarm.

At 11,000 m from the surface, Eagle returns and places the support feet down. The braking rockets reduced the drop speed to 90 km/h.

At 4,000 m from the ground the Eagle computer issued a new alarm message. “1201” cried Aldrin. Houston’s response was “Ignore” because it meant an overload similar to the previous message.

At 750 m, Armstrong takes manual control. The soil was more rough than expected. In a few seconds, Armstrong selected and discarded some possible appetizers. The jet of the Moon lifted dust and stones and sprayed the pilot's field of view. The fuel was running out. Finally,

Armstrong decided to pose among the dazzling dust clouds. The contact was very soft “I had to look at the light of the posing sensors to make sure that the soft bump I felt was posing,” recalls Aldrin.

Before stepping on the moon they had to match the cabin with the outside pressures. Six hours later, at 2.53 a.m. on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong said ‘That’s one small step for … man, one giant leap for mankind’ when he put his right foot on the dusts of the Sea of Tranquility. He took three or four steps back and then started kicking the dust of the Moon. “The surface is made up of fine dust. With the tip of the boot I am surprised. The first impressions on the Moon were “in thin layers sticking to my side and to the ground like charcoal dust”.

Aldrin descended after the ship.

The astronauts had a great job over the next two and a half hours: Collect the moon stones (21 kg), take pictures, open the US flag and prepare different sessions. Using a TV camera installed on the ground you could see your images on Earth.

Between 1969 and 1972 another five Apollo missions managed to settle on the Moon and another (the thirteenth alafede!). failed.