Medieval Science

Among them stands out Roger Bacon. Although his criticism was direct from the current point of view but too advanced with respect to the atmosphere of that time, he had no great influence. In this respect the XIV is more important. made at the beginning of the century by Duns Scoto (1265-1308). This was demonstrated in Oxford and Paris and expanded the field of theology that Aquinian considered foreign to the demonstrations of reason. The fundamental doctrine of Christianity, according to Scotus, is based on any divine will and the main gift of man, much greater than reason, was election.

Hence, somehow, the field of philosophy and theology liberated each other and philosophy did not become the “admiration of theology.” This liberation would involve the development and freedom of knowledge and the introduction of experimentation in the field of philosophy laid the foundation of the science we know today. However, this was not achieved day by day. XIII. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 14th century the worlds of philosophy and theology were separated between the Aquines and the Scots.

The enthusiastic follower of the path undertaken by Duns Scoto was William of Ockham. In his opinion, no result of theology could be reasonably proved. Moreover, he highlighted the inability of the rationality of some manifestations shown by the Church. He fought against the Pope's doctrine of supremacy and led the Franciscan war against Pope John XXII. For all this he was considered a hero and locked up. But after fleeing the prison he put himself under the shelter of the Emperor of Bavaria, who helped the long discussion he had against the Pope.

Ockham recognized the two sides or types of truth; dogmatic truth (accepted through faith) and philosophical truth (to be investigated through reason). This attitude was associated with the renaissance of nominalism. According to this, the only existing reality is that of particular things. Universal ideas, on the other hand, are only pure names or concepts of intelligence. Aquinas or "realists" were abstracting from the universal to the particular. On the contrary, thanks to the resurgence of nominalism, attention was focused on the objects we can grasp through the senses and, incidentally, abstractions were viewed with total distrust. Over time, this would mean direct observation, experimentation and induction research.

The Church rejected and banned the new nominalism and the University of Paris condemned Ockham's writings. In that university, in 1473, that is, during the Renaissance, they wanted to put realism back as an official doctrine. But Ockham's ideas were completely rooted and continued in them. Ockham's work ended the priority of medieval scholastics. Since then, philosophy did not necessarily have to reach the conclusions that theology showed, and seeing the free mind, it could go to the research of its subjects.

The other thinker who fought the scholastic is Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464). In his opinion, all human knowledge is conjectural, although God understands all that is hidden. This is possible through mystical intuition. These cults led the Cusa to pantheism. This pantheism would then be assumed by Bruno. Aside from ideas about knowledge, Cusa carried out physics and mathematics: through the balance that showed that plants took part of the weight of the air as they grew, he proposed the restructuring of the calendar, he worried strongly about the career of the circle, defended the theory of the Earth's turn rejecting the system of Ptolemy. Opening the way to Copérnic, Bruno, with astronomer Novara, formulated the theory that number is the only absolute by its relative movement.

Mathematics and Physics

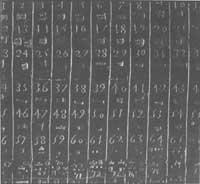

If in the field of science one should highlight a vertex in the field of mathematics, the acceptance of Arab figures would be the ease of calculations obtained through them. At first these figures were written in “apices”, that is, in branch tokens, to be used in the abacus of Gerberto (10th century). These new figures were written on dust-coated panels immediately.

In this way, you could clean and rectified what was carried and the provisional results: XII. and XIII. For centuries the “algorithms” demonstrated this use. When the paper was then reduced and its use extended, so that the written calculations could be done without being erased, it had to adapt to the form we currently use. Arithmetic was necessary in trade and from 1340 Genoa was known double party accounting.

In arithmetic, along with geometry (i.e. algebra), the secondary equation began to be published. Along with the Fibonacci seen above, the XIV. It is worth mentioning in this field the late Nicholas of Oresme at the end of the twentieth century. This added a new level to the long chain of achievements. It is due to the sum of series, the first bases of analytical geometry and the invention of exponents, among others. He also dealt with the dynamics of Nicholas of Oresme and thus showed himself in favor of the turn of the Earth, since “although the heavens move during the day and the Earth cannot be demonstrated by observation” is a simpler and more perfect theory of the turn of the Earth.

One of the major changes in mathematics in the field of physics was the theory that all real differences could become differences between quantities. As Crombie indicates, the intensity of a quality (e.g., heat) could be measured as the magnitude of a quantity. Qualitative Physics of Aristotle and the XVI. The difference between mathematical physics of the 20th century lies in this change.

XIII. From the 20th century onwards, physics underwent a great impulse: the static hand of Jordanus Nemorarius, the magnetism with the appearance of the compass, the optics in the Oxford school, especially in the Thierry of Freiberg, etc. We should take into account the means and the situation to properly judge this stage of the Middle Ages, and perhaps Beaujian's words make us:

Ptolemy, Aristotle and Galen appeared as huge giants. His works were erected as great fortifications. The man of the Middle Ages opened in these walls a series of tears, but it was closed inside. The future was going to prove that here and there, instead of making a criticism or a mistake, the road was all crushing. A revolution had to be made: Kopernik against Ptolemy, Galileo against Aristotle and Harvey against Galen.