CAR immunotherapy: a door to hope

Oncohematologist Izaskun Zeberio Etxetxipia proudly talks about her work. After his research and work at the Hospital de Navarra and the Cancer Center Memorial Sloan-Kettering (New York), since 2014 he has been at the University Hospital of Donostia. It is the reference of the Lymphoma Unit and explains that they provide daytime care to patients without admission: “We try to avoid admission because for the patient it is much more pleasant and tender.”

He is a direct witness to the evolution he is experiencing in treatments and lives first hand the door opened by immunotherapy. She explains that the classic treatment is chemotherapy: “To understand it easily, cancer cells are cells that reproduce more than enough and do not die, and chemotherapy cuts the cell cycle.”

In immunotherapy the focus is another: instead of putting the force on the destruction of the cancer cell, it is placed on the boost or increase of the immune system. “That’s exactly what they gave the 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine,” Zeberio recalled. “Thanks to these studies we know that tumor cells are hidden to prevent the immune system from detecting and destroying. They sent a signal to create a protection zone and handed the Nobel Prize to those who developed monoclonal antibodies that blocked those signals.”

Today monoclonal antibodies are still used, but in addition, CAR cells have acquired great strength: “They have awakened great hope. A hope based on evidence, not too much,” he said.

According to him, they have been researching with CAR cells for more than twenty years and numerous clinical trials have been conducted, especially in the US and China, which have already reached the clinic: “It has been possible for a year to apply this therapy in the public health system.”

The core is a chimera

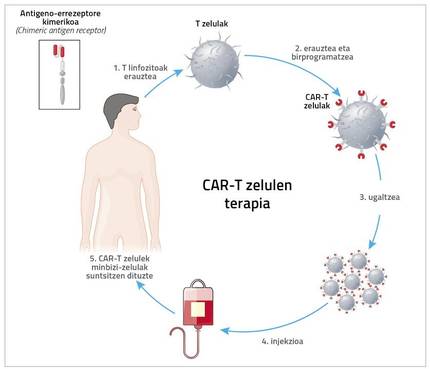

The acronym CAR means chimeric antigen receptor chemical. To do this, the patient is removed from the immune system. “It’s usually T cells, so it’s called CAR-T therapy. But it can be done with other cells, such as NKs. Cristina Egizabal Argaiz, from the Centre for Transfusions and Human Tissues of the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, is carrying out very interesting studies with them”, explains Zeberio.

However, what has now come to clinical application is CAR-T cell therapy. Therefore, the patient is extracted T cells and, through a very complex and expensive process, a new receptor is introduced to this T cell. Thanks to this receptor, the T cell has a great ability to detect and destroy cancer cell antigens.

And hence the name. Zeberius: “Kimera is a monster of Greek mythology made up of fragments of goat, lion and dragon. Well, in the chimeric receptor a mixture of B and T lymphocytes is performed. The part of B lymphocyte detects the antigen and that of T lymphocyte penetrates the cell and gives signal of activation and reproduction.”

This technology can be designed for different antigens. Zeberium indicates that in hematology predominates an antigen, CD19, so the CAR-T cells used are anti. “Therefore, the greatest development and the best results have been obtained in B-line cancers where the CD19 antigen is expressed. Especially in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, that is, in childhood leukemia. In addition, all non-Hodgkin B lymphomas (90% of the lymphomas we treat) express CD19.”

From research to clinic

Based on the results of clinical trials, in 2017 the American Food and Drug Agency, FDA, approved the commercial use of CAR-T cells and was approved a year later by the European Medicines Agency, the SEM. In Spain, since November 2018 it is possible to use therapy in centers.

“It’s very important to choose patients who really benefit well,” says Zeberio. “It is true that it has generated very high expectations, since these patients have no alternative, but it must be taken into account that it is necessary to choose well those patients who will benefit treatment, because the procedure is very complicated, very expensive and can have serious side effects. It’s not for all patients and we have to decide very carefully who to give it to.”

“Also, don’t forget that therapy has significant side effects.” In fact, the patient is first removed from T lymphocytes and sent to the US. There, through retroviruses or lentiviruses, they introduce a receptor to lymphocytes. Then they reproduce in the laboratory and are sent back. Meanwhile, it may take 5 weeks to analyze how to treat the patient. Once arrived the cells are incorporated into the patient.

When receiving patients, Zeberio explains that there is toxicity during the first two weeks: “Therefore, the patient must be in good condition. Keep in mind that there is a struggle between the T cells you have received and the cancer cells and other cells of the patient. A cytokine storm occurs that can cause shock and respiratory failure. Then we have to take care of the patient in special care.”

No wonder, therefore, to underline that they must act responsibly. “We must not forget that this therapy was accepted with very few cases. Since its results are so satisfactory in patients who have no alternative, it has jumped very quickly from researchers' trials to hospital practice, but we must rigorously measure safety and efficacy. Somehow it’s like they’re in the 3rd clinical phase.” Ultimately, the priority is to cure patients, but at the same time they are learning and improving.

In addition to the storm of cytokines, he points out that sometimes neurotoxicity occurs. They still do not understand the mechanism very well, but there are patients who suffer neurotoxicity, from confusion, to the difficulty of writing or speaking, through coma. To address these risks it is clear that the patient must be strong at the time of receiving modified lymphocytes.

Zeberio says: “Doctors must measure benefits and risks, and we will only apply treatment if the benefit is greater than the risk. Not for everyone.”

Strict criteria, detailed plan

In Spain, the Advanced Therapies Plan establishes the criteria for the implementation of CAR-T treatment. The object of the aforementioned plan is literally the following: Organize in a planned, equitable, safe and effective way the use of CAR and currently CAR-T drugs in the public health system, as well as their research and production in the academic field of the public health system under conditions that guarantee quality, safety and efficiency standards.

Zeberius sees the plan with good eyes. He says it is very important to centralize cases and that groups are well prepared. Experience is also necessary: “It’s not your experience. Teamwork is critical in medicine and these therapies more than anywhere else. Patients receive treatment in the hematology service, but it includes the work of professionals of different services, all of them with training of nurses, intensivists, neurologists, infectious, immune... That is, you need an interdisciplinary, well-trained team.”

Therefore, rigorous criteria are necessary. According to them, in Spain there are eight centers designated to include CAR-T cell therapies, which are not few in relation to the European population. In Euskal Herria there is none, but Zeberio considers that there is nothing wrong: “Things must be done well. In the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country there is a plan and it is decided that in the future the University Hospital of Donostia will be a center of CAR therapies. We are preparing for it.”

In the meantime, patients are monitored at the Donostia-San Sebastián University Hospital itself, but they are sent to one of these eight centers for treatment. For the time being, optional patients are those with line B tumors with CD19 antigen, but Zeberio hopes that over time this technology can be used in other tumors such as solid tumors. The door to hope is increasingly opened.