The conquest of the Arctic

The North Pole has no owners. Not yet. The property of the five countries in the area, Russia, USA, Canada, Greenland (Denmark) and Norway, reaches 200 miles off its coast. This is established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). And what remains outside are the international waters or, in this case, the ice. But at the bottom of the sea under this international ice there are precious treasures. According to experts, there is a lot of gas and oil in these lands. In addition, the melting of the North Pole makes these lands increasingly affordable. And, of course, no one is willing to leave this kind of treasure without its owner.

The Russians also placed their flag on the Arctic seabed last summer to proclaim that these lands were Russian. It was nothing more than a symbolic gesture and at the moment has no value, but the Russian plan is to appropriate much of the Arctic. They want to take advantage of an opportunity offered by the United Nations Convention. But they are not the only ones, Denmark and Canada want to take at least the same opportunity to seize those lands.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, adopted in 1982 to resolve the conflicts that occurred in the exploitation of marine resources, has now been ratified by 155 countries, with an important exception in the United States. According to the Convention, a country's exclusive economic zone reaches 200 miles off the coast and has exclusive rights to exploit the area's resources.

But the Convention includes the possibility of making exceptions. In fact, Article 76 states that property can be obtained from areas located more than 200 miles, if it is shown that the area is a natural extension of the country's continental shelf with geological criteria. Countries that demonstrate this can choose between setting the new limit to 350 miles from territorial water limits or 100 miles from a 2,500 meter deep point.

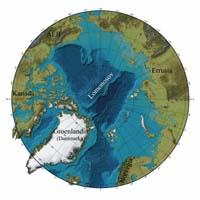

And on the basis of this Article 76, Canada, Denmark and Russia want to seize some areas of the Arctic. One of the keys within the plans to achieve this is the Lomonosov ridge, a 1,800 km underwater ridge that from Siberia heads towards Greenland through the north geographic pole.

Thus, researchers from the three countries concerned enter the submarines and icebreakers and investigate Lomonosov. They want to show that the Lomonosov ridge is a natural extension of their countries. Perhaps it is rare in the middle of the Arctic Ocean that a tuft that is several miles from all coasts can be considered an extension of Eurasia or America. But behind there is a curious geological history of the ridge.

Banished Tuft

In the 1960s, the Atlantic dorsal -- an oceanic dorsal located in the center of the Atlantic, where a new ocean surface is formed -- reached the Arctic, called the dorsal Gakkel. According to a theory they published at that time, the seabed of the Siberian area opened as a new surface emerged on the Gakkel ridge. As a result, the Lomonosov ridge, initially a sliver of the shore of the Eurasian continent, moved away from the continent until it was between Greenland and Russia.

In 1991, a German icebreaker and a Swede began testing this theory. When they performed the first seismic study they saw it clear. In the Eurasia area of the ridge a series of characteristic structures generated by the distance from the ridge of the continent were detected. And on the other side of the ridge were thick layers of sediment. That is, the surface of Eurasia was much more recent than the other side. On the other hand, in 2004 the first samples of land were taken from the Lomonosov ridge, which showed that they were very similar to the continental shelf of Eurasia. Thus, there is no lack of evidence to affirm that Lomonosov was a part of Eurasia.

But, although the origin of Lomonosov is clear, if the Russians want to own those lands, they will have to figure out where the ridge relates to Russia, if it is associated anywhere. In fact, some theories argue that the ridge was disattached from the continent, and in that case it would not be a natural prolongation of Russia strictly. But it is not easy to respond to this problem if no more data is collected.

The Russians made their first request to appropriate an Arctic area in 2001. Then, the United Nations commission to make those decisions did not accept it on the grounds that more evidence was needed. It is not clear what kind of evidence they need, but last year Russia launched another research expedition to collect as much data as possible.

For their part, Denmark and Sweden also sent an ice whisk last year to the research of the Greenland group in the Lomon, on the Lomonosov Ridge of Greenland expedition (LOMª) 2007. It was necessary to open the sampling path between very thick ice sheets and the collected data have not yet been published. But, like the Russians, they want to see if it is related to the continental shelf of Lomonosov Greenland or, at least, know where exactly that platform ends to know which Arctic land they have the right to ask for.

Canada also has possibilities, as the southern end of the ridge is right between Greenland and Canada. And they are also investigating. However, the most urgent are the Russians. According to the Convention of the Sea, a country has a period of 10 years since its ratification to make requests for new areas. This deadline ends in 2009 for Russia, 2013 for Canada and 2014 for Denmark. It is not much time, if you consider that in the area you can only investigate a few months a year.

You cannot know what these conquests will end up in, but you may need to redraw the map lines. This will be decided by the Commission designated by the Convention. And that decision may also not be final; in short, not everyone accepts the Convention and those who ratify it today can also change their minds in the future. But in the meantime, those who do not want to lose that golden opportunity are engaged in sharpening scientific weapons.