The hard childhood of reef fish

Coral reefs are the refuge of almost a quarter of marine life. They are home to more than 4,000 fish species, 700 coral species and thousands of other plants and animals. There is great animal diversity in the numerous hideouts, cracks and cracks among coral colonies: sponges, worms, molluscs, crustaceans, hedgehogs, stars, holoturies and brightly colored fish.

Colorful Party

Coral fishes are beautiful, the richness of their colors, the rarity of their forms and the diversity of their behavior is incomparable.

They live near the substratum of the reef, and their diversity of colors is due to the characteristics of the place of residence --the tropical waters are transparent and the background is often close, often covered with invertebrates of various colors-: the colors camouflage them with mimicry, those of the same gender facilitate their knowledge or attraction, or they function as signage marks of the territory to express to others their belonging. In some cases, such as swordfish, a striking suit is worn before reaching sexual maturity; others, such as crossbowmen, cover the body with stripes so that they more easily discover the mixed reflex; and in other cases, it serves to warn of the colors, to realize that those spectacular thorns can die with the simple touch, like the lionfish.

This strategy is twofold. The wide variety of colors and the low speed of swimming make reef fish can not abandon the protection granted by the reef and mark themselves to the open sea. They would be too easy prey for large external predators. Puppies have no other solution.

Under Rapids

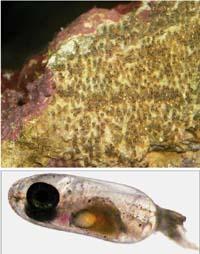

Coral fish are oviparous, that is, they reproduce with eggs. Most, like surgeons, live in nets and throw their gametes into the water when the breeding season arrives, where they are fertilized and unprotected in the middle of the ocean: they are pelagic eggs.

Regardless of reproduction, most species form pelagic larvae of eggs, small transparent fish that become part of plankton. Thus, the life of 99% of the species is divided into two main phases: the planktonic larva phase (oceanic) and the maturity phase (coral reef). These two forms of life will probably be the part that most separates these animals from those on earth.

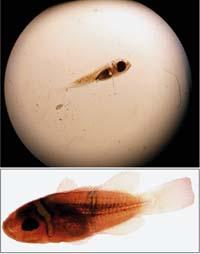

At birth, larvae are transparent and very different from parents, who cannot swim against ocean currents and take them away from the reef. In the beginning they are fed through the yolk sac they have from birth (used as a deposit for the abundance of nutrients) and subsequently fed plankton. With the passage of time they grow and acquire the characteristics of adults; in the end, they find a place to settle in the reef to reach the youth. In this time of consolidation, most larvae suffer from metamorphosis: they produce colors and scales, and they are highlighted a major change in behavior. Most settlements take place at night to prevent predators from seeing them.

The two sides of the txapona

The larval period is very important and has many advantages. One of them is the dispersion of eggs and larvae to other areas of the reef, with the consequent lower risk of extinction of the species. If a species were alone in a small place, it could disappear as a result of a natural catastrophe or human action.

Such was the case of Pterapogon, the kauderni or the Cardinal of Bangaii, a species that incubates its young in the mouth and that, having no pelagic phase, only stops in a small area of Singapore and is in danger of extinction due to pollution and fishing. In addition, more than 60% of the reef species are predators, so it is not the ideal place for the development of small larvae and they are more likely to survive in open sea.

However, not all larvae reach maturity, as predators, food shortages, ocean currents and adverse physical conditions cause high mortality. Thus, recruitment changes can occur, that is, in the number of larvae returning to the reef, which affects the size of the adult population. Despite the importance of all these factors, larvae of many coral fish depend on 'transport' to reach adult habitat (reefs); without 'transport' to reach the reef, coral fish larvae will not survive.

Fine swimmers

Previously it was thought that the larvae were dispersed simply until, dragged by the currents, they reached a place to settle and develop. However, recent scientific studies have shown that they have highly developed sensory capabilities and those necessary for swimming, allowing them to return to the original reef.

Coral fish larvae are strong in the last stages of development and good swimmers, reach speeds above sea currents and can swim for several hours without getting tired. Larvae can swim an average of 40.7 km without getting tired (some reach 140 kilometers) for an average of 86.7 hours (maximum 288.5 hours). Swimming fast and able to reach far, they are more likely to return to the reef, especially if they detect driving signals. Some experiments have revealed that to be able to orient, navigate and reach the reef they use auditory, visual, chemical and stimuli of different kinds.

Strategies to return home

Most larvae have eyes from the early stages of development. They can orient the sun, moon, stars, polarized lights and magnetic fields. The fish have a very developed vision, but since the underwater view does not exceed 50 meters, they can only use visual signals at small distances.

Many coral fish larvae respond to changes in the concentration of chemicals dissolved in water. Chemical stimuli can be abiotic (salinity, temperature and calcium carbonate) and biotic (amino acids, fatty acids and alcohols). All of them are of animal origin and communicate to the larvae the presence of living beings. Larvae use these chemical stimuli to settle at small spatial scales (10-100 meters) and navigate at larger spatial scales.

Many fish larvae, such as whites, goats, cardinals, and maidens, use olfactory signals to locate the place of birth. Larvae can separate odors in ocean currents, choose the reef they were born on, and use these signals to return them. To find and guide the way home they need developed sensory systems and mechanisms.

Other species of fish use sound. Sound travels more easily in the water and larvae using sound signals do not have to fight against currents. For a long time it was thought that the fish did not sound and the aquatic environment was called 'silent world'. However, during World War II, when sonar and microphones began to be used to detect the noise of enemy submarines, they knew that sounds were heard in the water and that at times there were great confusion.

Among the fish that live in the coral reefs can be heard many and very different sounds: the cry that the parrot fish make when grinding the branches of the corals, or the one that make the fish to put, the one made to attract the other sex, used as a sign of danger, or the sound that the crabs do with the tongs, the waves, the rain, etc. Thanks to these sounds, many larvae, especially the cardinals and the maidens, find in the ocean the way to the 'house' and, many kilometers away, can be oriented to reach the reef in which they were born.

When they approach the coral reef, the larvae become sexually immature juveniles and acquire the typical characteristics of the species. After a period of time (each species has its own), reach sexual maturity, seek a member of the other sex and after the courtship fertilize the eggs, then retake the cycle of hard life.

When in the documentaries we see them swimming peacefully in the reefs, it does not seem that these colorful fish have had to face so many threats since birth, before reaching those beauties and glimpses of maturity that they show before the camera.