Andean coca: harmful or beneficial?

The abusive consumption of drugs called cocaine extracted today by young people from Europe and North America has brought proposals to eradicate crops in South America. But we should know that with these measures we are disappearing one of the cultural characteristics of the Andean world. Coca has a profound meaning in the daily life of the peasants, even at a magical-religious level.

Farmers chew coca leaves to relieve fatigue and/or thirst and hunger. As recognized by the World Health Organization itself, O.M.E., you cannot consider oman cocaine that takes any amount of cocaine.

The illicit market of cocaine and political-military alliances in Latin America have obscured the degenerative effect of this “shameful custom” and that “custom”, only in Peru, is found in more than three million inhabitants.

What are, however, the effects of this plant, long considered as divine? Is it harmful or beneficial to the organism? Do its inhabitants use any method to obtain cocaine?

Origin and history of coca

The word coca is aimara and cechu1: it means “food for walkers and workers”. The exact origin of coca is discussed among archaeologists, botanists, anthropologists and linguists. The oldest testimonies on the use have been found in Ecuador: BC the well-known statuette of the “masticator” concordance of the year 3500. BC. Boats with coca leaves dating from 2500-1800 have also been found.

In fact, the archaeological data do not clarify the origin of the coca or its antiquity. The explanations of botanical science place less than two thousand meters in the ecosystem “eyebrow” of the Andean jungle. Coca is a permanent green shrub of the temperate valleys of the Andes of the East. It is also cultivated in Sri Lanka, Zantzibar and Australia. The ecological location of the plant is a humid and temperate medium.

Erytrhoxylum coca belongs to the family of the Eritroxilaceans and is a shrub 1-3 meters high. Its branches are scarce, with leaves 3-5 cm long and 1-2 cm broad. The flowers are white and small and the fruits are very striking red berries.

Although the coquization was the custom of the Andean natives, before the disaster of the Inca empire its use was limited. After the Spanish conquest, it was linked to the magical world of indigenous people and was forbidden by the Catholic church. However, taking into account the income obtained thanks to its trade, it was accepted and a custom was introduced that was not Inca in the day to day of the non-native: it began to take mate (infusion), but many Spanish also chewed. Garcilaso de la Vega himself, of Inca origin, in his book 2 “Los Reales Comentarios de los Incas”, collects the following words of Blas Varela:

“…most of the income of the bishops and the canons of the cathedral of Cuzco comes from the coca leaves (…) and with it has enriched the Spanish dedicated to the sale. Despite not knowing all its virtues, there are many people who have said and written many things against the plant (…) and now there are magicians and sorcerers who offer coca to their idols while increasing the number of people who believe it should be forbidden.”

In the years after the Spanish conquest, coca continued to be linked to the life of the natives and, moreover, it was practically unknown in the whole world, apart from the data collected by the ethnographs and botanists of the colonial troops.

In 1855 a new interest arose around the coke. Gaedake isolated the alkaloid that he baptized as erythroxylina, which allowed confirmation of some trips of American origin and of certain virtues that the European receptors added to the plant.

The medical-scientific uses of cocaine confirm its stimulating and anesthetic effect. The following year, a paper was published on the effects of cocaine, although no one fixed on them.

In 1880 the phenomenon of cocaine appeared. However, US authorities did not prohibit until 1930 the use of cocaine for Coca-Cola production. Until the 1970s it was widespread in literary, political, commercial and scientific environments around the world, international health institutions. They rediscovered the work of the twentieth century.

Coke values

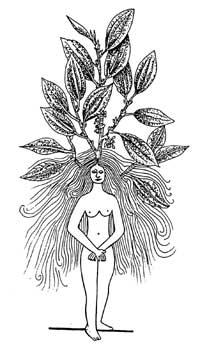

To express the origin of coca, the Andean tribes have invented numerous legends. They make us better understand the phenomenon of coke, its social dimension and its consequences.

In Colombia, the oral tradition of the Cogi Indians brings together three narratives, each more complete. The first one says:

“…Koka Gualchovang or Ama Lurra was the gift of the Earth, which through the hero Sintana turned a female body into the first coca tree.”

The second says:

“…To the daughter of Sintana, Bunkeijm, a shaman gave him coca leaves. When he returned, seeing that his father had died, he put leaves in his mouth. The sintana sneezed and resurrected, removing from his mouth the butterfly mass.”

The third legend:

“…A shaman named Teyuna wanted to get coca leaves. In his day he discovered a woman who produced desired leaves by stirring her long hair. Undoubtedly, against his father's opinion, he disguised himself as a bird; the girl went to the river that swam and drank through her mouth. She asked the girl if she wanted and, by accepting, she discovered that the bird became a naked man who removed the costume and embraced the bird with enthusiasm. When he returned home, Teyuna shook his head and two coca seeds fell. He planted and grew a beautiful plant. A part of it was given to all the neighbors, so it was extended to any place.”

The legends of Bolivia and Peru are not so imaginative and, although they explain the sacred feature of the plant, highlight the divine characteristics “… to relieve choking, fatigue or hunger and give more strength to human beings”.

The habit of using coca leaves in the mouth is ancestral and today it is very widespread among the Indians of the Andean highlands, but for many years it has been neglected by the superior human groups as a popular tradition. The legend of “degenerative influence” was extended in the consumed race, including the risk of dependence, the dissolution of identity and the relationship with sexual behaviors of perversion. The coqueros are sent too quickly.

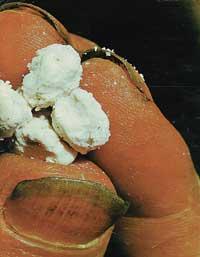

To understand the effects of the usual consumption of coca leaf on users, scientific studies were initiated in 1939. London’s “Latin American World” published the results of its first research. The gradual chewing of coca leaves confirmed a rapid anaesthetic reaction in the mouth and stomach that impregnates the feeling of hunger and an innovative effect on organic functions. At high altitudes it helps to maintain the respiratory rhythm and protects against diseases of the stomach and dental caries.

In the sixties, a group of scientists from Harvard University investigated the composition of coca and compared it to other Andean plants. The results were published in 1976 and surprised by the researchers themselves. Coca, like cereals and legumes, has a very high energy content, but it has many more minerals and vitamins than these (see table on page 33). It contains a very high content of vitamin A and basic trace elements (Ca, K, P and Fe) as well as complex vitamin B. These data, together with the stimulating and anesthetic effect, indicate why locals appreciate it so much.

Dr. Carlos Monge, founder and director of the Institute of Andetian Biology of Lima, has carried out research on this plant. The direct observation of the place showed that the human being coca is an important element for the adaptation of the climate of the Andes to thaw and oxygen to October. In fact, typical diseases of other mountain cultures (pellagra, beri-beria, scurvy or rickets, for example, caused by lack of vitamin B7, B1, C and D, respectively) did not appear.

Following pharmacological traditions from the time of the Inca empire (or earlier), indigenous people use coca as a drug. Roasted coca relieves pucci colic and mixed with anise and infusion of chamomile, is also burned. In the form of cataplasma it is used against rheumatic and muscle aches. For care, it is used in the form of compresses mixed with fresh urine, cane brandy and vinegar. In infusions or chewing relieves the pain of the teeth. In the premises intended to relieve conjunctivitis and headache, semi-chewed coca leaves are placed together with nutmeg.

After a copious meal and in case of sore throat, it benefits from the coquera mate. As can be seen, the uses are numerous and the only prejudice is summarized by the following sentence that the user must remember: “Clear sleep, stimulate the heart, but the nerves do not.”

Coca and the bad mountain

The Andean mountain range, located to the west of the South American continent, has a length of 8,000 km from Venezuela to the south of Patagonia, crossing Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, Chile and Argentina. Always with snow-capped peaks over 6,000 m, being Akonkagua (6,960 m) the highest. Although the human body has problems adapting to the altitude of these high lands, the Incas and other peoples live there.

Mountain disease or the one known in South America as soroche appears at altitudes above 3,000 m and can cause death. The main causes of the disease are the decrease in the partial pressure of oxygen as the altitude increases, the decrease in total pressure and the greater effect of solar radiation. At very high altitudes, cosmic radiation and air ionizations aggravate the disease.

When it rises slowly, the most important factor is the decrease in oxygen to breathe in the air or the highest concentration of carbon dioxide in the tissues. Both affect all people, but not to the same extent. There are no specific rules on the effect of altitude on the organism. The ability to adapt depends on people and partly on their genetic characteristics. The disease of the mountain has been fatal in about 3,000 m, but most people perceive it between 3,500-4,000 m. The most common symptoms are: headache, nausea, dizziness, dry cough, intestinal confusion, insomnia, lack of appetite, tiredness, faster heartbeat and need to breathe.

All this is because, together with the acceleration of the respiratory rate and heart rate, the organism makes a huge effort to compensate for the lack of oxygen. In severe cases these symptoms are aggravated with confusion, indifference with external stimuli, lack of coordination and loss of consciousness, decreased heart rate and respiratory arrest.

Most of the problems derived from altitude disappear for a few days, but if not, you must go down as soon as possible. The difference could be 500 m. And conversely, a rise of 500 m can cause symptoms. There are no fixed rules, so we saw it. The following table shows our data. Although they are not representative in scientific terms, in it you can see its consequences for those who do not practice mountain sports. These data have been grouped into two typologies and three altitudes depending on the appearance or modification of the symptoms of soroche.

Little knowledge of the climate adaptation process. The observations made, especially in the Himalayas expeditions, indicate that adaptation to the climate is usually long and difficult; the higher, the more rough. The great remedy to combat soroche in the Andean altitudes is the coca mate, an infusion of coca leaves that can be taken in any cafeteria. In most of the houses and hotels of Peru and Bolivia (banned in Ecuador), the mating cup, nice and green waiting to receive the foreigner, resonates immediately.

The cayman and the helmets that have lived for centuries in these lands have adapted to the oxygen deficit. Despite its small size (159 cm. On average between men and 147 cm. Among women), their lung and pectoral capacity is high and appear to be strong bodies. In addition, Dr. Carlos Monge said they have more hematins and hemoglobins and a higher volume of blood. 8 million red blood cells in front of 5 million people living at sea level, twice as much hemoglobin and half a liter more blood. The heart rate is also slower. With these characteristics, Peruvian pilots climb more than 7,000 meters without oxygen mask.

The adaptation to the altitude makes it difficult for the inhabitants of the Andes when they approach the coast. They are those who then suffer the “mountain disease”. Your body perceives symptoms similar to those described above. “Every time I go down to Lima it accelerates my heart, it costs me to breathe and I’m almost not hungry, that’s why I’m wishing to return to my Cusco…”, said Echevarria, an expert in Andean culture. Despite this denomination, he did not know where his ancestor was from the other side of the Atlantic.

Coca and ancient incas

The Inca empire spread throughout the Andean mountain range, from Ecuador to Chile, building the villages more than 3000 m, thinking it was the ideal height for corn fields. The extensive areas of cold lands, more than 4,000 m high, were used for forage crops and tubers. The coke and cotton, which need more heat, were planted below 2,000 m.

Coca was part of the Andean world and occupied a prominent place in religious ceremonies. It was a sacred plant, necessary in the rites of magic and prediction, in sacrifice and xamanism. The plant was offered on many occasions in the HUs, where there were 5 and mummies of emperors. In the great days ceremonies were held before the emperor and his court. In a large fire, prepared for these holidays, coca was burned with corn and guindilla.

During the trips, coca served to reassure the gods who lived in crosses and caves and what is more important, allowed the traveler to measure time. The cocada was the time that a walker took with a load of four basins (45 kg) in his back to chew a ball of coca. The terrain was flat, ascended or descended in slope, the road traveled was different. Each coca ball took between 35 and 40 minutes to chew. During this time, coca had a stimulating effect and gave time to the person who was loaded to travel 3 km in plain and 2 in slope. The walkers had a fixed space previously established to rest. There they were replaced by a new ball of exhausted coca and resumed before 10 minutes. The daily work was done by taking between six and eight glasses.

In the Inca empire coca had a high therapeutic value. Thanks to the skeletons and the ceramics discovered we know that the medicine and the Inca surgery were very superior. They used forceeps, turnstiles and climbing, for example. In all important interventions, it seems, coca was used as an anesthetic to sensitize patients. They also poisoned or hypnotized Chicha.

So important was that on other occasions coca was not used at the time; it was a monopoly of governors, priests and doctors that penalized if fine villages were consumed. With the disaster of the Empire the punishment also disappeared and the custom of chewing coca spread, but to the point that it was excessive, with the increase of the commercialization of crops and plants. This expansion of customs is undoubtedly due to the scarcity of food, which replaced coca. The best economic and social conditions could reduce coke consumption.

Future of the future

Koka is part of the Peruvian and Bolivian peasant life. It is used to live in a hostile climate, relieve fatigue, and complete food shortage. Many of them still do not know the relationship between coca leaves and cocaine. The “divine” Inca plant is still used as a drug, even in some social and religious rites. The reasons for the extension of crops to large forest spaces should be sought in the ambition of drug traffickers, in the pacts between them, and in the political power of the American continent.

The 1961 Vienna Convention included coca in the list of prohibited psychotropic substances. It was then that the struggle that has only meant the expansion of coca began. For this reason, a group of politicians, artists, lawyers, trade union leaders, economists, peasant leaders and intellectuals of Bolivia signed in 1994 a manifesto requesting the resolution of the agreement of the Vienna Convention. They want to remove the coke sheet from the list of prohibited narcotics to allow domestic consumption and, incidentally, eliminate the illicit business that grows and increases.