AIDS treatment session with bone marrow transplants fails in macaques

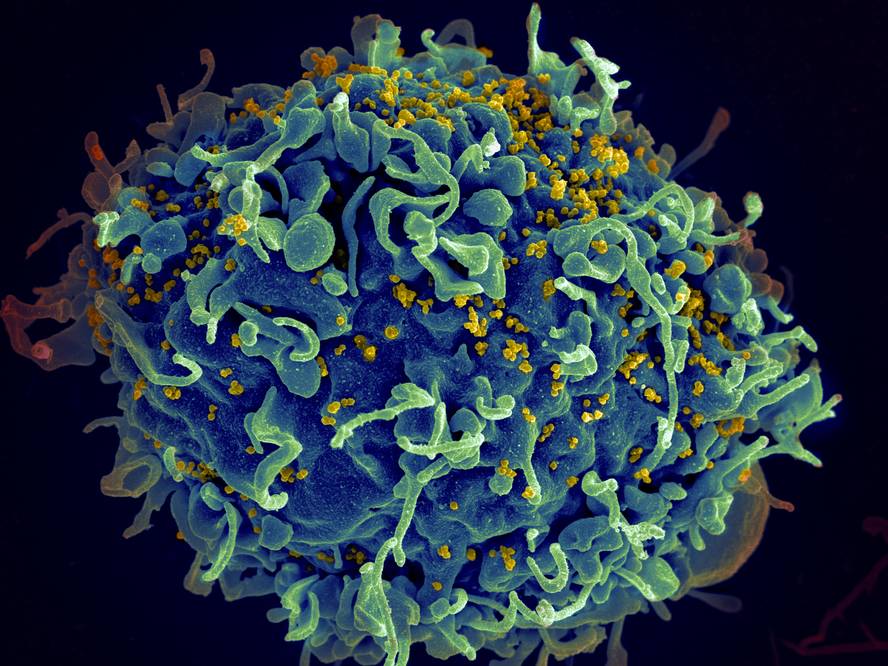

Six reshus macaques have been tested that were infected with the SHIV virus produced by the combination of human immunodeficiency virus and apes and treated with antiretrovirals for a time to assimilate the concentration of the body virus to the state of the people in treatment. Patient Berlin then undergoes half of the treatment for radiation therapy and bone marrow transplantation. Finally, antiretroviral treatment was eliminated to all to measure what was happening with the virus concentration.

The results of the trial, published in the journal PLOS Phatogens, indicate that the treatment has not served to eliminate the virus from the body of macaques. As expected, radiation destroyed almost all cells in the blood and immune system of macaques and, therefore, SHIV viruses, which are the cells of the immune system they target. However, once bone marrow transplantation has been received and the immune system recovered, the SHIV virus concentration has increased rapidly at the time antiretroviral therapy has ceased. In two of the three models collected in the transplant it rose as quickly as in the control group; the third was mistaken the kidney and post-mortal studies showed that it had no virus in the blood but had virus in the tissues.

The key to the mutation?

This is the first animal session to analyze the bone marrow transplant hypothesis, but it has a big difference with the case of the patient Berlin. In fact, the bone marrow donor received by patient Berlin had an hiv-resistant mutation. This mutation prevents the function of the CCR5 gene, so no protein is generated that facilitates the penetration of HIV into human cells. Without this protein, people who have mutated the two copies of the CCR5 gene have their own HIV protection.

Researchers believe that the reception of mutated bone marrow cells has much to do with the recovery of the Berlin patient. According to the general hypothesis, radiation destroyed the cells of the patient's immune system and with them HIV; subsequently, due to the intrinsic protection of new cells of the immune system from the transplanted bone marrow, although nowhere in the patient's cells have remained HIV, it has not been able to expand again.

Because the macaques used in the trial did not have such a mutation, researchers at Emory University have been unable to analyze the entire hypothesis. They have also recognized that they have worked with a very small sample and that broader research is needed to have solid conclusions.

The data collected among human beings are also very limited. In addition to the patient Berlin, four other cases with similar results are known worldwide: two in the United States and two in Australia. In both cases in the United States, HIV infection returned after the interruption of antiretroviral therapy. In Australian cases, patients continue to take antiretrovirals, although the virus is not detectable after receiving bone marrow transplantation.

However, from the beginning researchers have warned that a bone marrow transplant is not viable for the treatment of AIDS, since the procedure would be too dangerous.