Nylon, precursor of synthetic fibres

In 1928, chemist Wallace Hume Carothers started working for the American company Du Pont. Specifically, from the research of various natural polymers - cellulose, silk and caucho-, it was intended to obtain synthetic materials similar to these.

Carothers' team soon achieved a synthetic polyamide of silk-like structure. However, it was discarded, since, despite its structural similarity, it did not present the characteristics of the silk - its resistance and flexibility -. The researchers continued with the research of polyesters, since they could be more easily manipulated than polyamide.

While working with one of them, Julián Hill, a Carothers colleague, made a discovery that would have a fundamental importance in research. Hilli came up with putting a small polyester ball at the end of a rod and starting to pull it off, and as the polyester stretches, he discovered that a silky thread was formed.

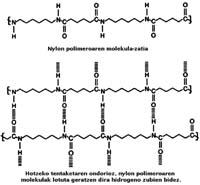

They say that taking advantage of an afternoon that he left for the city of Carothers, it occurred to the investigators to test where he could try it. Hill and his companions placed a polyester ball at the end of the rod and began to pull it out. Then they realized that the more stretched the stronger. Cold tensioning was discovered, a process by which the polymer molecules are reoriented and the polymer is strengthened.

6.6 polyamide, the best fiber

The melting point of the polyesters was too low to be used in the textile industry, so it was thought to apply cold stretching to initially discarded polyamide.

Polyamide polymers are polymers that have amida type joints (CONH), obtaining different types of polyamide depending on the monomers used in their production - basic units. This is what happened to one of the researchers in 1935, do different types of polyamide.

In total it prepared about 80 polyamides, but of all of them, the polymer that was made on February 28 was subsequently marketed, specifically 6,6 polyamides. Carothers himself preferred to commercialize another polyamide already manufactured, polyamide 5,10, a material better and interesting than polyamide 6,6. The price of polyamide 6.6 was lower, so Du Pont decided to market it.

This polyamide, later known as 6,6 nylon, was made by reacting two monomers extracted from benzene, by reaction of adypical acid and hexamethylene diamine. As for the form of designation of polyamide, they were based on the amount of carbon of the monomers; in the case of nylon 6,6 both the adypical acid and hexametilendiamine contain six carbons.

Success of Nylon

Nylon was marketed by Du Pont in 1938. Initially it was used to make the bristles of toothbrushes, but certainly the greatest success was the nylon socks. They were first sold in New York on May 15, 1940 and in five hours about 4 million pairs of socks were sold.

However, as a result of the Second World War, the production of nylon socks was discarded; the Japanese army prevented the importation of the silk that was brought from far east, so all the production of nylon went to the war to manufacture parachutes, sleeping bags, tents and ropes of boats among others. The results were very good with nylon. In 1945, at the end of the war, nylon was used again to make socks and it was then when the famous socks arrived in Europe.

Since then the nylon industry has travelled a long journey. Although in the market there are several types of nylon, the most used are 6.6 nylon and 6 nylon. Both are very important in the textile industry, but they also have other uses, such as the fishing materials industry, rods and dental brushes. Nylon, although synthetic, is a sign of survival.