Susan La Flesche: doctor for the people

It came through the snow storm, in the trolley of the two mares' run, sheltered in a buffalo fur coat, on the return of a long time trip to care for a sick man. When he came home, on the portal he was waiting for a row of people, some rough, other burning or painful… all waiting for Dr. Sue. Dr. Sue's working hours never ended. Even when I was going to sleep, I would turn on a flashlight in the window, so anyone in need of help knows that they would find there.

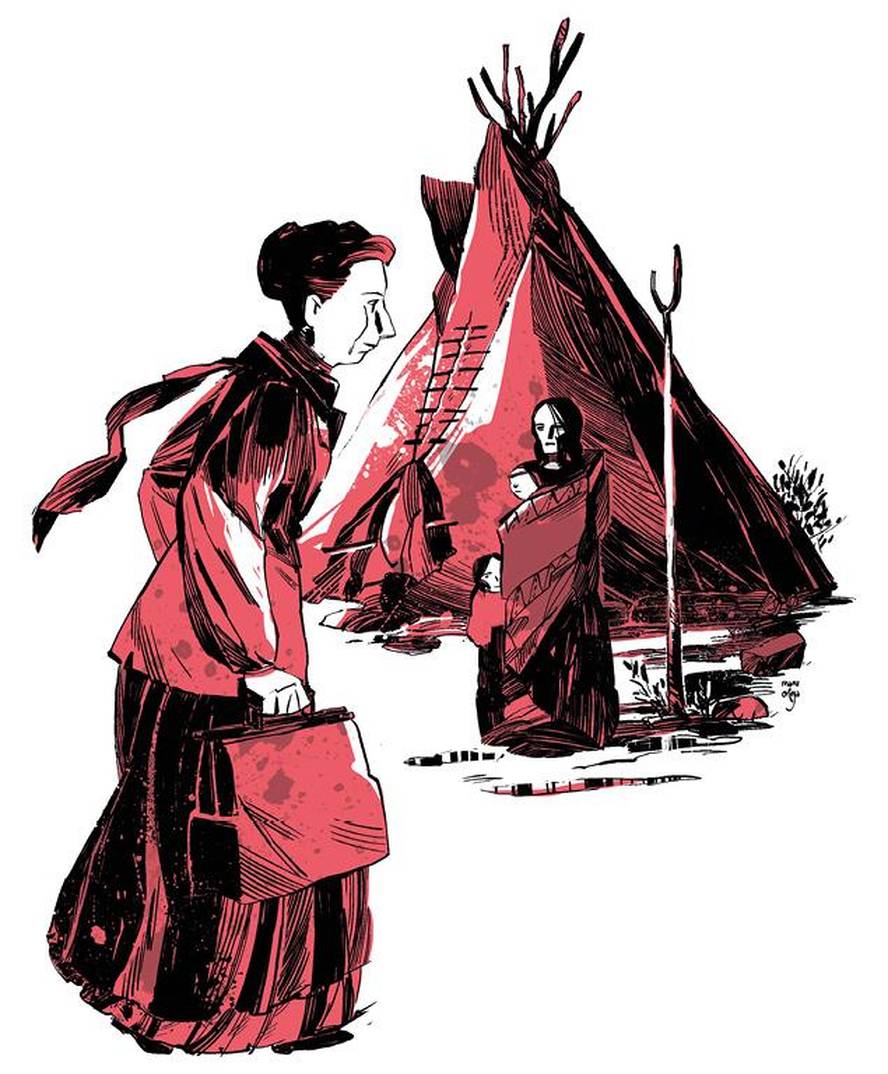

“Ever since I was young, I wanted to study medicine,” wrote Susan La Flesch, Dr. Sue, and by then I saw it clear that my people needed a good doctor.” When I was eight years old, I had a lived passage: She spent the night with a sick old woman. He was called four times and every time he promised that he would go immediately. The woman breathed the last air before sunrise. The white doctor never showed up. For him, after all, he was an Indian woman. That's what Susan felt that night, and she had to do something to change it.

Susan's father, Joseph La Flesche, was the head of the town of Omaha, Iron Eye. He considered it essential to unite the two cultures (white and Indian) so that the people could survive. “Civilization or disaster, there is no alternative,” he said. Omaha, without abandoning culture, was in favour of learning new languages, religions and cultures to enrich the knowledge of new neighbours. Therefore, the daughter, along with the teaching of her language, songs, customs and beliefs, sent them to the Presbyterian Mission School, so that they could also learn the language and customs of whites. Do you want them to always call you "those Indians"? Or do you want to go to school and be someone in the world?” he said.

At the age of fourteen, Susan took the train with her sister to go to New Jersey Young Elizabeth School. After two years there he moved to Virginia, the Hampton School where the daughters of the former slaves and the indigenous were raised. There they taught him to do the jobs that a woman had to do. But Susan was clear that that was not her way. I wanted to study medicine.

At that time, the most privileged white woman also had to overcome major obstacles to being able to study medicine. The Flesch, being indigenous, is more. But he did. She got admission to the Pennsylvania Women's Medical School and a scholarship to be able to pay for those studies. He was the first Native American to graduate in medicine.

In 1889, at the graduation ceremony he spoke: “Those of us who have been educated must be pioneers of Indian civilization. Whites have reached a high level of civilisation, but how many years have been necessary for this? We have only just begun, so do not shrink us, but help us to climb higher. Give us a chance.”

I had no right to vote because I was a woman and I was not a citizen of American law because I was Indian, but I was a doctor. And with that knowledge, he returned to his hometown, the Omaha Reserve, at the age of 24, to become a doctor for 1,200 people in a 3,500 square kilometer camp. Doctor and lawyer, accountant, translator, advisor, secretary…

One day he dreamed of building a hospital for his people. Meanwhile, I was walking at home, on foot or on horseback, and then on horseback, I was walking miles and miles, and I was traveling many hours to serve a sick person. And many times, in addition, they rejected the diagnosis made and all the questions they had learned from whites. And that is that not all omahas were at all in favour of the union of both cultures.

It gradually gained public confidence. In short, that doctor, unlike white doctors, spoke in his language and knew his customs.

She continued to break all social stereotypes and norms, after marrying she continued working, even after having two children. In their daily struggle, trying to deal with the ills of their people. He preached the importance of hygiene and used mosquito nets in doors and windows to prevent the diseases they transmitted. He also did abstinence campaigns, thinking about his father's times. And the Iron Eye was very clear that alcohol was a “loss of civilized and non-civilized peoples.” He turned against him and made the white alcohol salesmen stay out of the reserve. After his death, a year before his daughter graduated, alcohol returned to the reserve.

Some also sold land to buy more whisky. And Dr. Sue also fought this disease. She met her closely because her husband had big problems with alcohol. He was killed by malignant tuberculosis. The Flesche was widowed with two young children. But he didn't stop working either. Her daughter later told her that her brother and the two grew up for a while in a horse trolley, which her mother took to care for her patients.

He continued to do miles and hours in Zalgurdia, often in snow, at temperatures well below zero, to endanger his own health. It starts with chronic pain and breathing problems. He died in 1915, at age 50.

He was able to fulfill his dream a couple of years earlier. In 1913 he opened the first hospital in the reserve with his own funding. A hospital open to anyone in need, regardless of age, gender or skin color.