The ice stations of James Croll

He signed with the name of James Croll and until then no one knew him, but in the early 1860s he aroused the attention of the most leading scientists of the time. Suddenly he began publishing high level works. The one that caused the most stir was, without a doubt, the relative to the times of ice, which indicated that the cyclical changes of the earth's orbit could cause ice stations. He was a revolutionary. But who was that Croll who came out of nowhere? He was writing from the Anderson's Institution University in Glasgow, but was not a researcher or university professor, nor a student, but a goalkeeper.

Croll took forty years to give an opportunity to his vocation. He was born in a simple family, in 1821, in the Scottish village of Little Whitefield. Two out of four brothers advanced, James and David himself, a younger and more consistent year. James was also a man of weak health since childhood, and throughout his life he had many problems. He started late at school and finished soon, and also liked nothing. He left him at the age of thirteen, without much training.

But at that time he met Penny Magazine (published by the Association for the Dissemination of Useful Knowledge). This magazine aroused him a different interest to that of the school, especially the topics of philosophy and physical sciences. Those new ideas brought by the magazine were exciting. From then on he began to read and learn everything he could on his own.

"From the beginning, it was not the details and data of the physical sciences that caught my attention, but the laws and principles that were behind them," Croll later wrote. "This led me to study in a systematic way, because to understand a certain law it was necessary to know the laws or conditions that preceded it. I remember well how before I could advance in physical astronomy I had to go back and learn the laws of motion and the basic principles of mechanics. I also studied pneumatic, hydrostatic, light, heat, electricity and magnetism. I had no help. In fact, there was no one around who had anything about these issues."

Croll became a wise teenager, but that wasn't going to feed him and at 16 he had to start thinking about what he was going to work. He would have liked to go to college, but the parents had no money. He learned as a miller. In the coming years he toured the entire east coast of Scotland to repair his mills. It was a hard job, all day on the road, and barely earned money. He left the job and returned home. And to school, because I wanted to learn algebra. There was the 22-year-old man, in class, among children.

Then Carpintero began. He worked three years, but the elbow was ossified and had to abandon it. Then sell tea and coffee in a shop in the city of Elgin. There he met Isabella and they married. Between them a hotel was installed but was not successful. He then acted as an insurance salesman in the Dundes, Edinburgh and Leicester. He did not like the work. When his sick wife moved to Glasgow, with her family. Croll took a while and wrote The Philosophy ot Theism. Then, for a year and a half, he worked as a journalist.

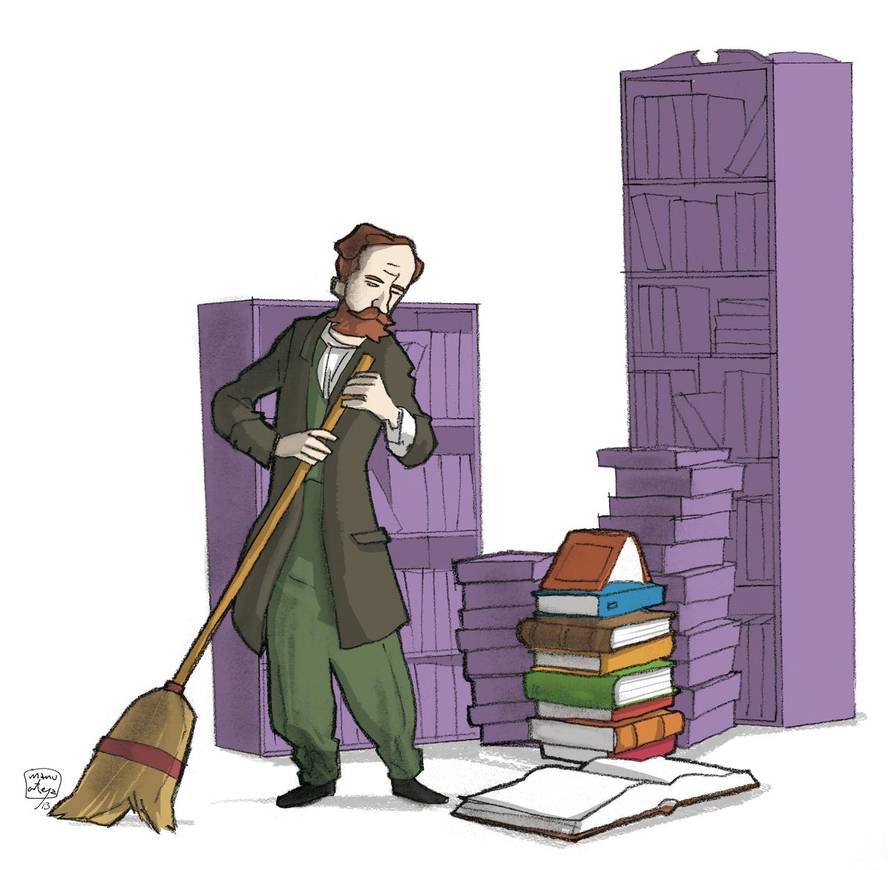

A post that would change his life at age 38: Conserje Square of the Anderson's Institution. The salary of a pound of the week hardly seemed to his wife, to live his brother, with whom he killed his parents. However, Croll was happier than ever. This work offered him a unique opportunity to continue learning. Anderson's had in his hands a magnificent library filled with science books. The tasks proper to the post were not difficult and many times he took his brother to work with him. Thus, while the brother did his works, he could be reading.

He soon began writing and publishing his research. All theoretical. He wrote many things, hydrostatics, electricity... but little by little he began to study how the movement of the Earth can affect the climate. It was Croll's most important contribution. In his work, published in 1864, Croll pointed out that at a time when the Earth was in full debate if the Earth was covered with ice, there was not an ice age, but there were several, due to changes in the earth's orbit.

He began to relate by letter to some of the most prestigious scientists of the time: Lyell, Wallace, Darwin, Tyndall, Hooker, Kelvin... Darwin answered him like this when Croll sent him his job: "I think in my life I have never been so interested in a geological debate. I just started to understand for the first time what a million... I thank you very much that you have cleaned up so much the mist before my eyes."

However, not all agreed with Croll's theory. Charles Lyell, for example, thought that geological reasons should influence much more climate than astronomical reasons. Lyell was preparing the 10th edition of his prestigious Principles of Geology and had the doubt whether he had to take into account Croll's ideas. He asked John Herschell what he thinks about what Croll was saying, who told him that the Scottish goalkeeper could function properly.

In 1866, Croll received a few pages written by Lyell, which were written for the climate chapter of the new edition of the book. After exchanging a couple of letters, Lyell sent him a copy of the book. Croll thanked him in another letter for the gift, as well as the good treatment of astronomical climate theory in the book.

Croll's name was growing. And in 1867 they offered him a job in the Geological Survey of Scotland. In 1875 he published the book Climate & Time. And the following year he was a member of the Royal Society and honorary member of the New York Academy of Sciences and...