The sweet discovery of Constantin Fahlberg

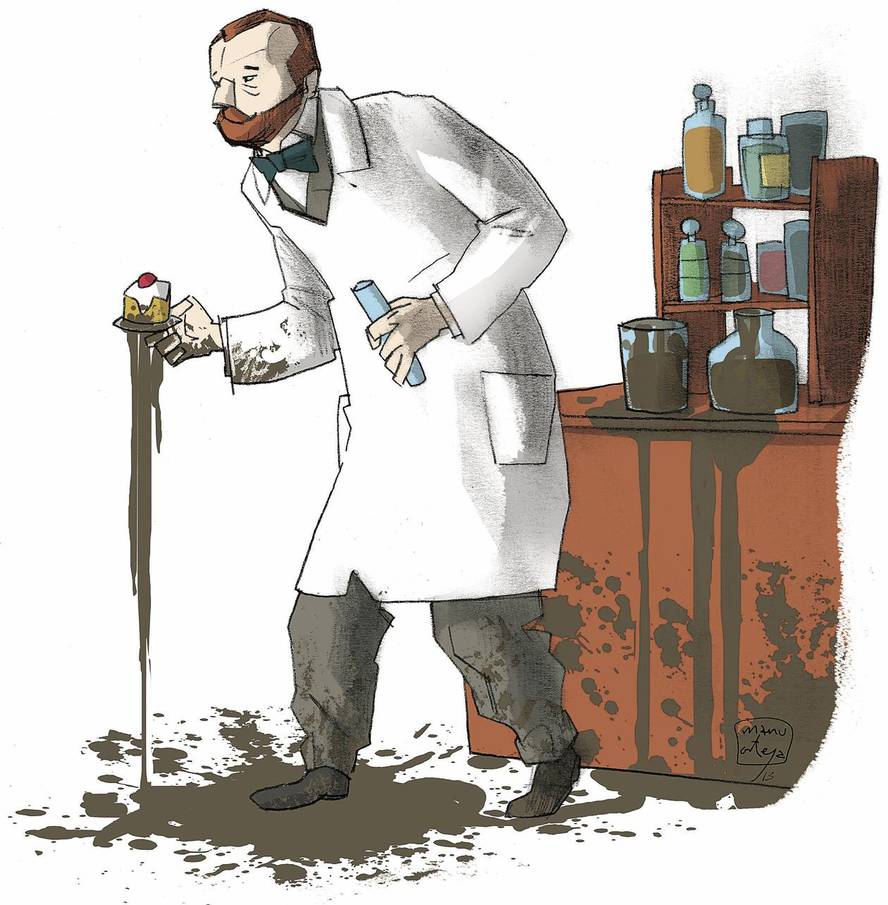

He had spent the whole day in the laboratory, working hard. The hours passed in the air and until very late he did not realize that he had not yet had dinner. He left everything the same and went out to the cafeteria at low speed. Perhaps they would still give him something for dinner.

He asked for dinner and sat at the table. Remove some of the bread and now. It was sweet. It was rare, but, who knows, maybe some sweet bread. He took some water and dried the mustache with the napkin. Surprisingly, the palate was sweeter than bread! He didn't know what to think, he picked up the cup again and another. This time it seemed simple! He suddenly realized what was going on. He explored the thumb for testing and yes, he was sweeter than the sweet he ever tasted! He was enjoying everything he touched: cup, napkin, bread.

Constantin Fahlberg thought of the origin of his sweetness in his fingers. It was clear: without knowing it, he created in the laboratory a new compound much sweeter than sugar. And as he left the laboratory without washing his hands...

The dinner was left and he ran back to the laboratory. Altered, he began testing everything in the flasks, test tubes and trays on his table. Fortunately there was nothing toxic or poisonous. And there he discovered it: in that flask, which remained boiled for a long time, orthosulfobencenic acid reacted with phosphorus chloride and ammonia, giving rise to benzoic sulfimide. That was the substance that Fahlberg enjoyed that night. He had previously synthesized it with another method, but of course he had never thought of tasting it.

It was curious that in Fahlberg's life a sweet substance appeared again. A couple of years earlier, in 1877, a Baltimore sugar import company hired the Russian chemist to analyze the sugar seized by the U.S. government for purity problems. The company also hired Johns Hopkins University chemist Ira Remsen to have Fahlberg conduct studies in his laboratory. In addition to studying sugar, Remsen authorized him to use this laboratory for his research. Fahlberg felt comfortable working there and told Remsen he would like to join his team. Remsen hired him in early 1878.

Remsen researched coal tar derivatives and Fahlberg began to do so. He made numerous discoveries, but without applications or commercial values. But that sweet substance was something else.

Fahlberg and Remsen started working with this substance. Purification, determination of chemical composition, study of its characteristics, search for the best methods of synthesis. And in February 1879 they jointly published an article in which they presented two methods of synthesis of benzoic sulfimide. They also said it was "sweeter than cane sugar." "When we published, people laughed like a scientific joke," Fahlberg said in a later interview with Scientific American magazine. "They criticized that work had no practical value."

Remsen himself also did not have much interest in the commercial possibilities of this compound, something he did not like, that he was a fan of pure science and whose only objective was the advancement of science. Fahlberg had other intentions. Leave Remsen's laboratory and say nothing about benzoic sulfimide: He called her "Sacarina de Fahlberg", playing with the Latin saccharum (sugar). It also patented a new method to produce saccharin in large quantities and at a lower price. Fahlberg presented himself as the only discoverer of saccharin without mentioning Remsen. In view of this, Remsen was angry, not because he wanted money, but because he wanted him to acknowledge his part in that discovery.

But Fahlberg followed him. It suddenly became one of the most prestigious chemicals of the time. Fahlberg and his saccharin appeared in the American and European press. And he started filling the mailbox: "I received up to 60 cards a day. People wanted saccharin samples, an autograph of mine, or my opinion on some chemical topic, to be a partner, to buy my discovery, to be my agent, to enter my laboratory, etc. ".

The first production of saccharin was launched in Germany. "I liked to start in this country [United States] because it's my home, but because of the high prices of skilled labor and the raw materials needed to make saccharin, I and my friends reject this idea," Fahlberg said.

However, in a few years he opened a store in New York. He and a worker produced 5 kg of saccharin a day. It sells in the form of powders or pills, with great success. It was used to add to drinks and as a preservative of tin foods. Doctors prescribed the treatment of headaches, nausea, obesity, etc. And for diabetics it was also excellent. Fahlberg was enriched.

As consumption of saccharin increases, concerns about its safety begin to increase. But Fahlberg was calm in that regard. Test conducted in 1882: He took 10 g saccharin and found that for the next 24 hours he had no harmful side effects and that almost the entire dose went into the urine without metabolizing. Therefore, it was shown that the substance was not in danger.

P.S.: The anecdote of discovery is the version narrated by Constantin Fahlberg in the journal Scientific American on July 17, 1886. Another version is that Ira Remsen found saccharin the same way (going from the lab to dinner home without washing his hands).