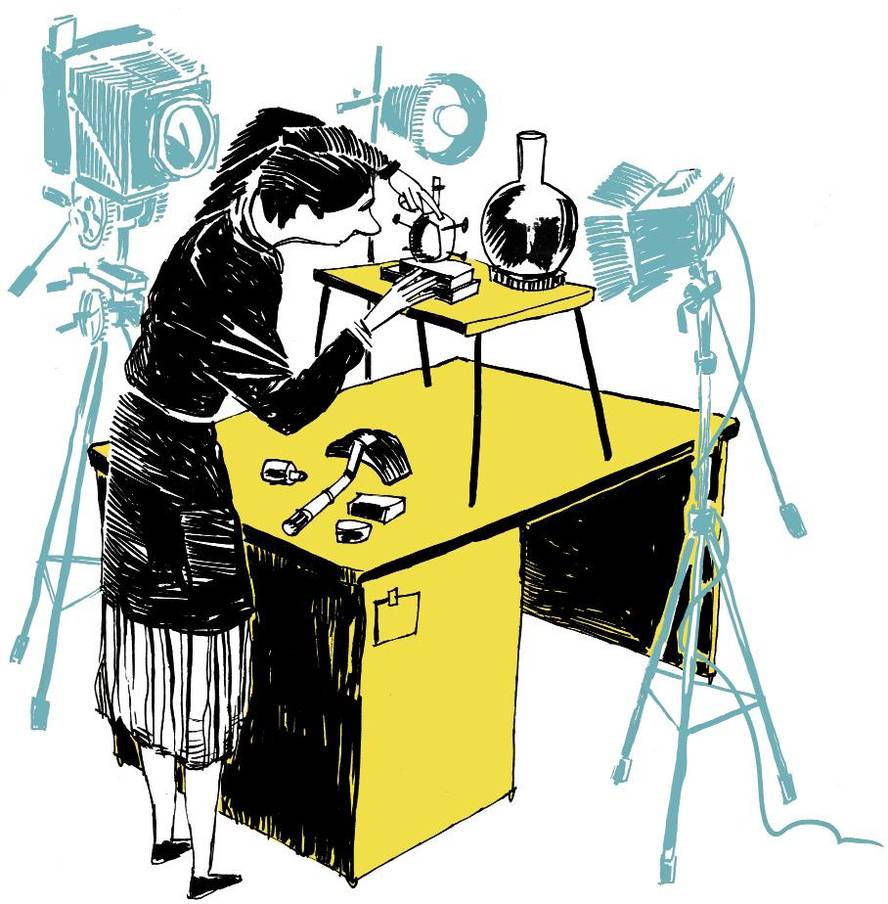

Berenice Abbott, science photographer

He was about to turn sixty when he went to a job interview at the prestigious MIT. She was an experienced woman with clear ideas. He told the interviewers: “You scientists are the worst photographers in the world and you need the best photographers, that’s what I am.”

It was the time of the Cold War, the year 1958. Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, was launched by the Soviets last year and the Americans realized the need to promote science. Among other things, they wanted to awaken students' interest in science and start teaching scientific subjects in a different way. To do this, it was decided to create a new teaching material. There the photographer Berenice Abbott found the opportunity he dreamed long ago.

Abbott was born in Ohio in 1898. He wanted to learn journalism, but in the end he studied sculpture in New York. He worked as a model for artists paying for studies. He posed for Man Ray, among others.

In 1921 he moved to Paris. It seemed wonderful, especially because there was an atmosphere of hope in the air. And there he met Man Ray, who also went to Paris, as many artists of the time. Faced with the need for an assistant, Abbott offers himself and he answers: “I didn’t think of a woman.” He still took it. Abbott worked hard and learned quickly. Three years later, Ray gave away a camera and encouraged him to take photos.

He began to portray artists and intellectuals. In 1929 he returned to New York and portrayed the city because he felt that need. It seemed to him the most vivid city in the world, he liked it passively and that is what he asked for his photos: that they attracted him with passion and that they were meaningful visuals. The result was Changing New York.

Abbott was a brave photographer willing to go anywhere. On a visit to the Bowery neighborhood, a man told him: “Good girls don’t come to this neighborhood” and Abbott responds: “I’m not a good girl. I’m a photographer and I go anywhere.”

When he finished portraying New York, he thought he should enter the world of science. In 1939 he wrote a manifesto entitled Photography and Science. “We live in a world of science,” he said. “A friend interpreter is needed between science and citizenship. I think photography can be that spokesperson.”

Abbott wanted to democratize science, get citizens, and was convinced that photography was the perfect tool for it. Little by little he began to perform various tests. He took pictures of agriculture, biology, technology. And it also began to invent and patent new photographic techniques and tools, among which the supersight camera stands out. With this camera, he managed to project the image to a greater extent in the film, obtaining increases without lumps.

In 1944 he worked as photo editor of the journal Science Illustrated. In that magazine he published one of the first images of the supersight camera: soap pumps. The photo showed the structure of soap pumps. The photo was for an article explaining how soap works to wash clothes. Surely they intended to reach a wider audience with this type of topics.

At first it cost him, but he was making a way in scientific photography. And he reached the top when he was able to work with MIT scientists. There, among other things, he took photos for the book of Physics. Abbott would turn the abstract concepts of physics into something he had never seen until then. He designed the photos and for this he had to understand the scientific concepts well. He played with light and dark, with estreboscopic light and the most appropriate techniques.

“The idea was to interpret science in a sensible way, with a good proportion, with good balance and good light to understand it,” he explained. “I think photography is a means to spread knowledge about our world, perhaps the best resource we have in these times. Photography is an educational method to bring to all audiences the truth about current life.”

Abbott enjoyed much of that time. He liked the team work they asked for those photos. Although not all were friends. In that world of men, many did not see with good eyes that an artist put the nose into science, let alone a woman. Once the photos were taken, Abbott had no decision about them and, once the book was published, was excluded from the project in 1960.

The book had a great success. For the year following its publication, a million copies translated into 17 languages were sold worldwide. The spectacular and clarifying images of Abbott were the key to success. And, subsequently, Abott's scientific images followed his path in other books and exhibitions.

Abbott continued to work. His work was his priority. She opposed marriage because when women married, they abandoned their interests. “I’ve never been worried about aging,” he said. Aging is natural. I do not understand why women are concerned about it. I don't understand why it pressures society. There is nothing more elegant than an old woman. He has lived so much… he has something that others do not have.”

And he had the opportunity to be elegant, who came to be 93 years old. “I’m so fascinated with this century that it keeps me alive,” he said once. “There I will continue fighting until the last minute.”