Results yes, limitations

Energy from the Sun, atmosphere, oceans and Earth, among which are complex interactions that result in a local climate. Logically, behind these interactions are the basic principles of physics: "Mass is preserved, also energy; according to Newton's laws, air moves from side to side, etc. explains the physicist of the UPV Climate, Meteorology and Environment Group, Jon Saenz. "Based on these principles of physics, climate models simulate the world climate," he says.

These basic principles are expressed through complex equations and resolved in supercomputers. Without a supercomputer it would be impossible to analyze the world climate system because, on the one hand, they have to solve a lot of terrible operations and, on the other, they have to simulate the world climate.

The substitution of all climate interactions and factors in models is impossible. One of these limitations is the very power of computers, "there are no computers with enough power in the world," says Saenz. Another is the degree of understanding of scientists, since they do not correctly understand all the processes that affect the climate, since it is an extremely complex system. Scientists are building models as they understand the functioning of the climate. Proof of this is that they introduce increasingly complex equations in computers to simulate the world climate.

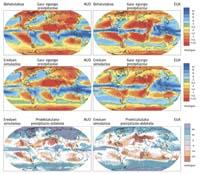

Saenz told us, however, that the intention of the models is not at all to completely replace the climate: "the system is complex and equations simplify the system to a greater or lesser extent." In addition, they simulate climate around the world and must simulate the world in their models. How is it done? Saenz explains: "You have to tell the computer at what point in the world you must solve the equations. For this we draw in the world an imaginary network that is divided into cells. In these cells we agree at what point we will solve the equations and consider that the values in the point-to-point range will be similar. The cells of the models currently used have an approximate distance of 100 kilometers. Discretization is the representation of the world through certain points. Of course, by doing that we always lose the information."

On the other hand, all models are based on the basic principles of physics, but when defining the expressive equations of these principles, they must simplify reality. Saenz explained this by an example: "Take, for example, moisture. In fact, when the relative humidity is 100%, it should rain. But we know that reality is more complex and that the humidity to rain does not have to be 100%. In models, however, it is necessary to simplify reality and fix in a specific humidity when it rains. For this we are testing. We define a series of humidity and see that the simulation of the model causes moisture to correspond to what happened in reality."

Like humidity, they incorporate hundreds of other parameters in the models. "However, not everyone who works with models uses the same parameters and does not solve the equations in the same way," said Saenz. "Therefore, not all models give the same results. Depending on the model used, one result or another is obtained," he adds.

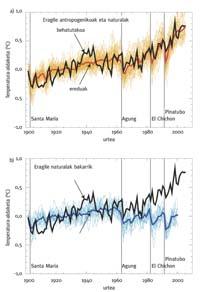

Despite all these limitations, Saenz has told us that they represent quite reliably the weather conditions of the past: "We have data collected in a lot of years and match situations that represent real data and simulate models. "The results are not very different, most are in a certain range of variability. It is logical to think, and that is what is seen in most cases, that the real value is within that interval." For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) uses simulations of 10-23 climate models to prepare its reports.

Instruments to predict the future

If they fairly reliably simulate the weather conditions of the past, it is to be assumed that they can also serve to predict the climate of the future. For this it is necessary to know the future conditions. And the truth is that it is impossible to know.

However, the objective of climate models is to somehow predict what climate will be in the future, taking certain possible conditions. The IPCC has established these possible conditions and proposed possible situations. The IPCC itself explains on its website the evolution of the population, economic development, energy demand, the use of energy, the availability of resources, technological changes, changes in land use and environmental policies.

They will define, according to the IPCC, human influence on climate in the future. "Then," Saenzek-says, "those who work with models incorporate in the models the conditions proposed for each situation and analyze the changes that could cause."

"These are not predictions but projections," Saenz explains. "Saying is making an ad is going to happen so much. The projections say that if these conditions existed, this and this would happen."

And there is, according to Saenz, the greatest uncertainty about the future climate: "The greatest uncertainty is not in mathematics, I think the greatest uncertainty lies in the situations proposed by the IPCC. It is impossible to predict how many people we will be within a hundred years, how much energy we consume, where we get from, etc. Who would say that 30 years ago the Internet would exist?"

However, all models suggest an increase in global temperature. So says Saenz: "What I can say is that the temperature does not drop. We cannot make an estimate, but we can say that the future will be warmer. And in this situation we must be cautious."

Skeptics at the end of uncertainty

It cannot be said that the issue is not complex, there are uncertainties everywhere. This allows interpretations in multiple ways. And, of course, there are those who take uncertainty to the extreme and question climate change itself. All kinds of arguments can be heard by skeptics. For example, Nils-Axel M rner, a retired geophysicist from Sweden, claims that sea level does not rise. He acknowledges that there are areas where sea level is rising, such as Venice or Hong Kong, but he believes the reason is that these places are sinking.

One of the most well-known sceptics of Euskal Herria is Ant n Uriarte. Uriarte focuses mainly on carbon dioxide. "The increase in carbon dioxide levels is beneficial because this improves plant photosynthesis, and there is nothing more to see than in the past, when the concentration of carbon dioxide was much higher than the current one, vegetation was abundant," says Uriarte.

Knowing how to address skeptics is not easy. The fact that someone who is not an expert on climate issues starts doing so is crazy: based on the same data, some do a reading and others do the opposite.

How to know, then, who is right? What is the truth? The most direct way would be to go to specialized magazines. In fact, in specialized journals, to decide whether or not to publish articles, that is, to know whether their arguments and data to protect them are reliable enough, they turn to and analyze other experts. It is the most objective form of screening.

If it is sought following this criterion, it can be observed that the arguments of skeptics appear very rarely published in specialized scientific journals. Naomi Oresi, a professor of history and scientific research at the University of California, analyzed articles published in scientific journals between 1993 and 2003. The conclusion was that no one bet on skeptics.

Oreskes did not find any articles of skeptics, but Clausura Martin Schutle, an endocrinological surgeon at King's College Hospital, analyzed the articles published between 2004 and 2007. Schutl concluded that 6% of the articles were against the official position.

When we talk about an official attitude, we are talking about an attitude that supports the IPCC, that the world is warming and will continue on that path. Someone might think that those who make reports are under heavy pressure from politicians, companies, etc. and that they somehow feel compelled to adhere to the official position. Saenz has not noticed, however: "The scientists who support the final IPCC report are not of any kind, they are already prestigious scientists and I think they won nothing for this work. That's why I think they're pretty objective."