Calorie reduction: eat less to live longer?

In these times when we live surrounded by food and with an increasingly sedentary life, we are observing that our life expectancy is constantly extending, increasing the incidence of diseases related to aging. Humans have struggled for generations to survive and not starve. But what if that is not the best way to live more and better?

Aging is a physiological process that can be defined as the accumulation of negative changes in cells and tissues over the years. Advances in the field of medicine allow us to extend our life expectancy more and more. However, these years that prolong in life expectancy, we often live with physical and psychological deterioration. Throughout history various theories have been proposed with the aim of explaining the aging process and, in passing, taking a turn to this process. For this reason, man in general and the scientific community in particular, has been longing to find the formula of the youth of always.

What if they told us that we have that formula before our end, and that we should not do anything new or invent it? Well, this formula exists and is called calorie reduction, or put it in other words: eat less, without eating worse. Since McCay and Crowell demonstrated that the halving (without malnutrition) of food to rats practically doubled their life expectancy [1], there have been many studies on this issue. Thus, given that in the following years and decades similar results were obtained in works with different living beings, from worms to monkeys, it was suggested that in species very different from each other an effect was repeated [2].

But how is it possible to help live calorie cuts more and better? Shouldn't it be the opposite? Research in this area has focused on identifying mechanisms that explain how nutrient availability can be beneficial to health. Laboratory work with yeasts, worms, flies and rodents identified proteins called sirtuins as responsible for the beneficial effects of calorie reduction [3]. This family of proteins deals with different and important biological functions. Among them it should be noted that in situations where nutrient availability is reduced, it acts as an “energy sensor” and the body adapts to this situation. In the case of mammals, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) performs functions related to energy homeostasis in tissues and organs of metabolic importance [4]. To do this, it introduces a series of changes in tissues and organs to optimize the use of resources. Among these changes, at the cellular level, we highlight the creation of new mitochondria (where cells produce most of the energy like ATP), the increase of resistance to metabolic stress and the removal of fats for use as fuel (since the availability of glucose is reduced).

These changes at the cellular level are reflected in tissues and organs such as the protection of the hypothalamus from degeneration caused by old age; in adipose tissue, fats are destined to the blood to be “burned” in the liver and muscles; the proper functioning of the liver is guaranteed and excessive accumulation of fat is avoided; the heart is protected from oxidative stress; cardiovascular tolerance to stress and stress is protected.

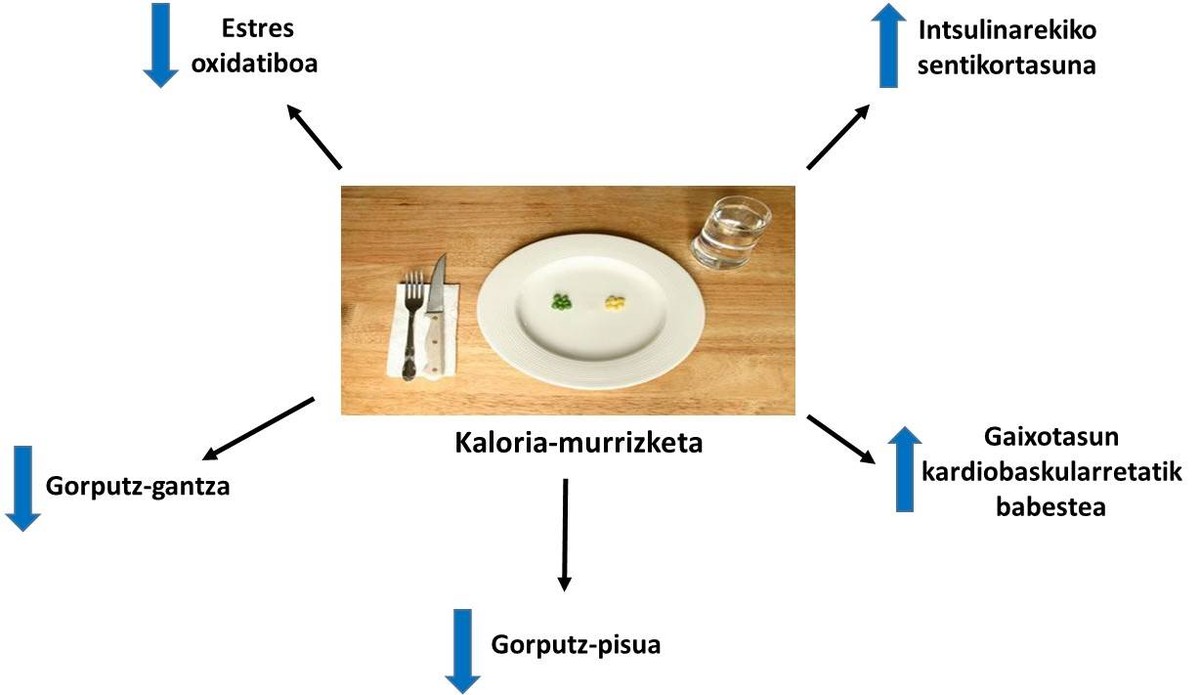

We know, therefore, that calorie reduction is an effective tool to deal with the adverse effects of aging, and we also know how it happens. But what is the right calorie reduction? Is it enough to eat half as usual? At this point it is advisable to clarify the concept of dietary reduction, since it is similar but not equal to calorie reduction. Calorie reduction, as the name suggests, will be based on reducing the amount of calories you eat and will maintain the distribution of macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins and fats) in a balanced diet. Calorie reductions are usually done by reducing the calories you eat daily by 20 to 40%. As a result, you can lose weight and protect yourself from ageing diseases such as diabetes or cardiovascular diseases. In the case of dietary restrictions, we can find two types of diets: those based on periodic fasting (which normally produce a calorie reduction of 30% per day) or those based on the reduction of a certain nutrient (in these cases a certain macronutrient is reduced without reducing the amount of calories eaten) [2]. There are some remarkable works on dietary restrictions, but the results in humans are not as clear as in the case of calorie reduction [5].

It can be said then that calorie reduction is an effective therapeutic tool that can have beneficial effects on the state of health, as long as there is no malnutrition (as for energy obtained in food and micro and macronutrients). However, what is not yet entirely clear is whether in humans this treatment is absolutely applicable which has proven to be effective in different models of experimentation. In fact, it can happen that the effects described in animals do not occur in humans, or that for various reasons (social, medical, economic…) humans do not follow this treatment.

If we take a look at the literature, we will find an example that calorie reduction works in humans and, in fact, helps extend life expectancy. This example is the case of the inhabitants of the Japanese city of Okinawa. Studies on the amount of calories that city dwellers ate during the sixties and seventies showed an average caloric reduction of 20% compared to people from other parts of Japan of the same age and sex. This caloric reduction would explain the greater life expectancy in Okinawa and the lower incidence of aging-related diseases [6].

In this way, it has been proven that reducing calories for a year by unobese healthy people helps to reduce body weight and fat content. In addition, this weight and fat loss is comparable to that caused by physical activity that equals the energy deficit generated by calorie reduction [7]. However, due to both infrastructure and ethical constraints, it is very difficult to analyze the influence of calorie reduction on human life expectancy. Therefore, biomarkers related to longevity are investigated in the work carried out on this topic in specific time periods [8].

Considering these examples, it seems that the primary calorie reduction problem would be for people not to reduce. And is that today, not having problems to get the food we want (always within our possibilities), who wants to stop eating? For this reason, in the last two decades, the search for molecular compounds called “calorie reduction imitators” has been a kind of passivity for the scientific community. The theory is simple: if the effects of calorie reduction can be achieved by taking a pill, eating what I want and without effort, why “suffer”? In principle it would be a solution to all problems, but that topic would give enough to write at least another article, so we won't touch it.

Therefore, it can be concluded that reducing the amount of calories in the diet will not make us immortal or keep us forever young. However, the knowledge gained on this subject since McCayk's early discoveries suggests that reducing the amount of calories we eat can help protect us from diseases directly related to aging. It can be said, therefore, that calorie reduction is the simplest way to get healthy to the day when you invent the formula of youth forever.

Bibliography

1. McCay, C.M. ; Crowell, M.F. ; Maynard, S.A. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of life span and upon the ultimate body size. 1935. Nutrition 1989, 5, 155-171, discussion 172.

2. Lee, C.; Longo, V. Dietary restriction with and without caloric restriction for healthy aging. F1000 Res 2016, 5.

3. Guarente, L. Calorie restriction and sirtuins revisited. Genes & development 2013, 27, 2072-2085.

4th He sang, C.; Auwerx, J. Caloric restriction, sirt1 and longevity. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2009, 20, 325-331.

5. Mirzaei, H.; Suarez, J.A. ; Longo, V.D. Protein and amino acid restriction, aging and disease: From yeast to humans. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2014, 25, 558-566.

6th Willcox, B.J. ; Willcox, D.C.; Todoriki, H.; Fujiyoshi, A.; Yano, K.; I, Q.; Curb, J.D. ; Suzuki, M. Caloric restriction, the traditional okinawan diet, and healthy aging: The diet of the world's longest-lived people and its potential impact on morbidity and life. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007, 1114, 434-455.

7. Racette, S.B. ; Weiss, E.P. ; Villareal, D.T. ; Arif, H.; Steger-May, K.; Schechtman, S.A. and Fontana, L.; Klein, S.; Holloszy, J.O. ; Group, W.U.S.o.M.C. One year of caloric restriction in humans: Feasibility and effects on body composition and abdominal adipose tissue. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006, 61, 943-950.

8th. Trepanowski, J.F. ; Canale, R.E. ; Marshall, K.E. ; Kabir, M.L. ; Bloomer, R.J. Impact of caloric and dietary restriction regimens on markers of health and longevity in humans and animals: Read more Nutr J 2011, 10, 107.