Darwin was not in Siberia

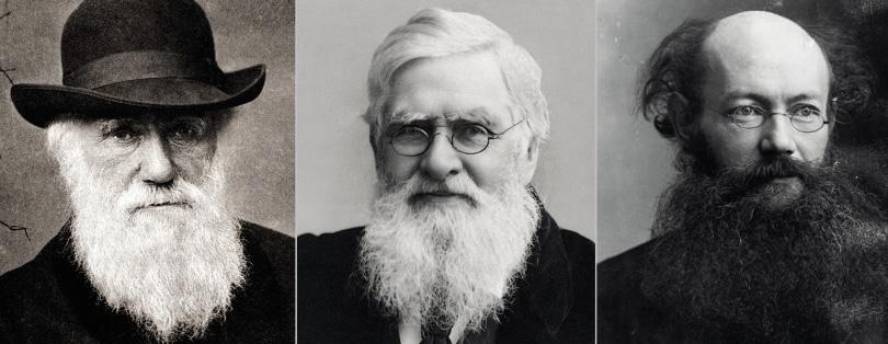

The influence of Malthus's economic thesis on Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace is known. If the socio-economic environment in industrialized and superpopulated nineteenth-century England left an evident mark on these naturalists, this is due to their predisposition. Both Darwin and Wallace found an unbeatable context to appreciate the importance of the fight for life between species (and individuals) in the rich tropical ecosystems. The consideration of the competition as an axis of natural selection led to its extension as a paradigm of coexistence of species.

Sounds of cold criticism

Although currently natural selection is a sensible mechanism for the evolution of species, it has not always been so. The publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, in 1859, dazzled. In Europe (and much later also in the United States), the most violent criticism of evolutionary theory comes from religion. In the sight of many believers, divine intervention in the origin of life which natural selection endangered. However, the sounds of criticism that emerged beyond Europe seemed to them another moralistic air. Its best-known representative is Russian Prince Piotr Alekseievitx Kropotkin, who claimed cooperation (and not competition) among individuals as the driving force of evolution. As Darwin and Wallace did, Kropotkin based his theses on natural observations, in this case on the scarce and violent ecosystems of Siberia. Faced with such a hostile environment, the animals (including humans) found themselves more united, more helped each other. From this observation, he claimed that positive interactions between species and individuals were fundamental to their survival.

According to Stephen Jay Gould, Kropotkin's theses reflected a wider ecological current in Russia today. In any case, those of Kropotkin, and as he himself formulated, are the arguments that had repercussions on the old Europe. The prince, in addition to explaining the evolution of species, used his natural conclusions as an argument to defend a socialist reform. Furthermore, we can say that he wanted to seek in nature support for his political positions, as did social Darwinism itself. History has taught us the wrong and cruel results of this kind of exercises (the conquests, racism and oppression of the working class have also been justified in the name of natural selection). However, the overinterpretation of the nature of the cropotkines, and especially the left tone of their arguments, meant the rejection of their theses after the Second World War, when the bases of ecological theory are established.

The new era of positive interactions or the resurrection of the prince

After a long century in the shade, studies on positive interactions between species have recovered in the last two decades. These interactions can benefit both species (mutualism) or one, provided that the other does not suffer damage (commentsalism). This type of relationships are often given between differentiated evolutionary lineages. The best known examples are mycorrhizae and lichens, as well as interactions between several plants and their pollinators. As Darwin himself observed (although he did not consider its importance from an evolutionary point of view), the diversity of positive interactions is enormous. However, and in order not to lose the thread of the thesis of Kropotkin, from now on we will refer only to the interactions of facilitation between species of the same trophic level.

In the facilitation interactions, a species transforms the conditions of the environment to benefit another or other species of the environment, increasing its growth, reproduction or survival. Unlike the relationships of parasitism, the species that facilitates the conditions does not suffer any damage. The mechanisms of facilitation that have been identified are diverse, including the improvement of abiotic stress, the acquisition of resources by increasing the decomposition and the cycle of nutrients, the attraction of water, etc., pollination, dispersion, protection against predation, the exchange of services such as the increase of the spatial and temporal complexity of the habitat, as well as the creation of new habitats. Indirect mechanisms such as “the enemy of my enemies is my friend” have also been proposed (the reader will find a number of examples in the bibliography of this article; see for example Holt 2009). To better understand all these facilitation mechanisms, the piled plants that appear in the high mountain are a good example. The strong growth of the cushion plants is an adaptation to cope with the climatic conditions of the high mountain (cold, dry winds, snow, sunshine). This growth guarantees a minimum surface and a maximum volume, so the plants are able to resist the cold during the winter and avoid water losses during the summer. The padding has a lower perspiration and a higher relative humidity, so species not fully adapted to high mountain conditions grow. However, in warmer and dry ecosystems, the transformation of microhabitat occurs under the protection of invasive plants. By detecting the original conditions in which some species evolved, it is possible that this process is key to advancing climate change. These examples highlight the importance of facilitative interactions in the management and maintenance of biodiversity and, incidentally, that in Kropotkin was not entirely wrong.

Positive and negative interactions, the two ends of the same string

The scientific evidence of the last two decades has shown that competition or simplification are useless. Ecological theory has quickly assimilated the importance of positive interactions by recognizing that nature acts in sokatira, sometimes from one side to the other. Having built the bridge between Darwinism and Kropotkin's theses, the main challenge is to understand when and under what conditions the relative contribution of positive and negative interactions changes.

In order to answer this question, the hypothesis of the stress gradient has been completed throughout the last decades. According to this hypothesis, an increase in physical stress should facilitate interaction between species. On the contrary, competition should be imposed as environmental conditions soften. These forecasts have been supported by numerous studies carried out in cold and dry ecosystems. However, critics with the hypothesis have wanted to put their generality into question, arguing that this situation does not occur against other gradients such as climate or gradients of water or food. Another of the weak aspects of research in favor of the hypothesis is the definition of the same stress, often too flexible, which has often been too anthropocentric (for example, are high mountain conditions really stressful for all plants? ). To resolve this debate, researchers have begun to review hundreds of papers published to date. Using the meta-analysis technique and once the methodological differences between the research were mitigated, and according to the strict definition of stress, favorable results were obtained. This study has confirmed that as the stress level (of any type) increases, the importance of facilitation mechanisms between plants increases. However, competition does not occur the same when reducing the level of stress. This research also has an added value, since it shows that the phenomenon is omnipresent. Therefore, although it is not always easily identifiable, the importance of positive interactions is not limited to certain ecosystems.

Darwin was not in Siberia but...

The reader had already heard of the title of this article. No, Darwin (nor Wallace) was not in Siberia, and what? As we have seen, this is totally insignificant, since positive interactions occur everywhere. In addition, Darwin knew during his trip the cold and stressful ecosystems, and probably could observe interactions of evident facilities. And we also know that Darwin paid special attention to mutualism, so we can hardly think that he did not reflect on the importance of positive interactions. The example, at least, would not lack them. If Darwin did not give them the importance that is recognized today is because he had no determination. Let us remember that for Darwin, mutualism (and it was not at all wrong) was an interaction derived from selfish actions. Modern ecological theory has partially recovered Kropotkin's theses to complete what was missing from Darwin. A whim of history avoided the encounter between these two characters and Wallace. In fact, Kropotkin went to European exile eighteen years after Darwin's death. Perhaps if he had gathered around a table to discuss purely natural subjects, the shadow of these one hundred years would be shorter.