Read in science fiction

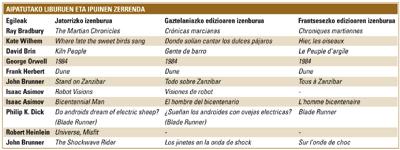

Perhaps space flight is the clearest example of science fiction technology. But it is not the only one. "The personal communicator appears in the movie Star Treck. They carried him in the chest, we in the pocket and we call mobile phone," says Miquel Barceló, one of the best-known editors of science fiction in Spain. However, the technical predictions of science fiction are not very numerous. In addition, many of the opinions about it are wrong. Julio Verne, for example, did not invent the submarine, picked up the idea of an invented device and used it.

There are few examples and some are doubtful or wrong. However, science fiction has been a good prediction, not science itself, but the use of science.

Sociology fiction

Isaac Asimov defined science fiction as literature that studies the response of scientific or technical changes to society. "It doesn't have to predict new science," says Barceló, "but it does explain the possible changes and how man adapts to those changes."

Cloning is a very clear example. Writers and readers of science fiction, accustomed to cloning for some time, reflected on the consequences of cloning. (A good example is Where late the sweet birds sang, novel by Kate Wilhem). But people outside of science fiction had to get used to it quickly when they cloned the Dolly sheep and appeared in the media.

This does not mean that science fiction writers have abandoned the subject, but work on a more advanced reflection. In his book Kiln people, David Brin explores a society in which clones of twenty-four hours can be made. It never seems possible to do something like this, out of ignorance, but the situation it poses can have real ethical consequences.

This is what David Brin himself said about 1984 by George Orwell: The year 1984 was not like that of the novel, among other things because Orwell wrote the novel. From a technological point of view, the book announced a fully interactive television (which allowed the viewer to spy on), but from a sociological point of view it carried out a deep and useful analysis of society from a possible situation.

Two examples: The story of Frank Herbert's book Dune runs on an almost waterless planet and John Brunner's book Stand on Zanzibar presents the problem of overpopulation. They are a mere ecological fiction.

The revolution of robots

Looking to the future, science fiction makes a very broad technological reflection. Asimov made the idea of the robot classic. For him -- as Robot visions says in his collection of stories and essays -- the robot was a human machine, a machine capable of performing the activities that we humans do, but, necessarily, it must have the capacity to think. It is the idea of mechanical man.

But it can go further. The abstract concept of the robot is that of artificial servitude: a machine with human intelligence that has no human biology and that will always fulfill the promise. Miquel Barceló believes that there is a contradiction in this idea. "If you attribute human capacity to a machine, it will not always fulfill the promise, because man wants to be free. It is the same idea as that of Spartacus; and that of the clay of the Rabbi of Prague; and that of the homunculus created by the alchemist Parazeltso, etc. XX. Those of the first half of the century are electromechanical robots of Asimov, which in the second half are replaced by androids. But in everyone there is the same story: that of revolution against the owner."

Asimov rejected the idea of revolution by inventing three laws of conduct for robots, with the help of publisher John Campbell. According to these laws, a robot cannot harm the human being, he has to fulfill all that man has promised and must protect himself, with the priority of that order. Stories about their robots are based on the paradoxes that create these laws. In the short novel Bicentennial Man, for example, a robot wants to become human and gets it without breaking the three laws. The three laws were programmed, almost carved, into the brain of Asimov's robots, which had no capacity to break the laws.

It is a total fiction, of course. But one reason to be fiction is that man has not developed those brains announced by science fiction. In short, we talk about artificial intelligence. There are currently robots, but they have limited artificial intelligence. Robots and software, in short, intelligent computers with movement capacity. They are not yet fully developed.

Intelligence under examination

It is difficult to say to what extent artificial intelligence must be developed to consider a robot as intelligent. Science fiction has turned this around and raises the reverse question: How do intelligent machines differ from people? Do androids dream of electric sheep by Philip Dick? In the book (base of the film Blade Runner), to detect the new androids that were commercialized, they had to invent new tests. And in reality tests have also been invented to measure machine intelligence.

The first of these dates from 1950; the English mathematician Alan Turing proposed a separation test of people and machines, the Turing test. Turing hoped that by 2000 there would be intelligent machines, that is, several machines would pass their test. But there is still no machine.

And, paradoxically, the fact that artificial intelligence has not developed much has computer applications. One of them is the Captcha system against propaganda. Many propaganda, the famous spam, are automatically sent by machines. For this reason, many blogs are protected from machines through Captcha: to send messages to blogs, often you have to fill out a form and a box to fill in is the Captcha test. It is considered that machines cannot overcome. For people it is easy. Therefore, messages that have not passed the test are considered as propaganda and rejected. Somehow, this system takes advantage of the lack of artificial intelligence.

Computers

In the problem of intelligence there are computers. In fact, these tests do not aim to differentiate any machine. Differentiate computers. In science fiction, however, the computer did not appear until the real computers appeared. We talk about robots and intelligence, and of course, intelligence is the result of an artificial brain. However, the writers did not know how the brain could be and, in fact, did not give that brain the computer condition.

Computer limit Fiction

The computer appeared and has since been exploited by science fiction. It has extrapolated the use of the computer and has found many possible sociological consequences.

Computer viruses have a striking history. It is unclear whether they were first created in reality or in fiction. In reality, the creation of an ARPANET military network was almost involuntary in 1970, with a program that jumped from one computer to another, called Creeper. "Hi I'm Creeper. Be surprised if you can," he wrote on the screen. He also prepared an antivirus against him, Reper. In science fiction, John Brunner took to the extreme a similar idea in his novel The Shockwave Rider, four years later. And many other novels used the concept of viruses at that time.

"We can't tell if the writers knew Creeper before they started writing. But it is clear that one thing is the story of a real virus made almost unintentionally and another approach is that a programmer has made a virus that attacks the system of his company when they expel him from the company. This approach has the classical architecture of a current virus, something that technologists of the time did not think. The perverse use of the virus was invented by science fiction," says Barceló.

One might think that the work of writers is simple. Science fiction spreads new technological ideas without explaining how these new technologies work. Writers invented a malicious virus and then computer scientists found a way to turn viruses into malignant ones. And something similar they did with other technologies.

But it's not that easy. In many cases it is very difficult to analyze society's response to new inventions from a realistic perspective. That is the main function of science fiction and will continue in it, we hope, for many years.