Loaders, the last links of the old industry

"Malla-Arrikoa was an experiment that went wrong." This phrase summarizes Juanjo Aramburu, director of the Museum of Art and History of Zarautz, the story of the Malla-Arri loader. Taken as such, the phrase may seem too harsh, but if we look at the data, it is noted that the Malla-Arri loader was not as important as others. However, it had its peculiarities and therefore are now being restored.

Restoration work has aroused the memory of citizens. The Zarautz Museum of Art and History organized an event in which testimonies of interest were collected. For example, one said: "Of course, what I've heard from my father and I've understood, if not, that it would work lying down [loaders], especially because there the burden costs a lot. Leaving winds and seas and lying down."

The difficulty of the site, however, was not the only cause of the indevelopment of Malla-Arri. Thus, some remember that the mining and industrial evolution also influenced the scarce activity of Malla-Arri, as shown by the following testimony (originally from Spain): "To make steel with the virtuous ones that were before, the originals had to be phosphates free to work them, and these were of good phosphate level. Subsequently other types of furnaces were invented and, in addition, that of other places was cheaper. This affected the closure of the operation."

From the mines to the coast

Construction of the loader began in 1907 by a Bilbao company, Mariano Corral e Hijos, for the Mining Company of Álava and Gipuzkoa, owner of the mining preserve located on the slope of Mount Ernio (Asteasu). The distance between the mine and the loader was 11 km and to join both points an aerial tram was used.

The tram was built with the three-wire Bleichert-Otto system. It had two subsections. The previous one, 10.7 km long, had three stations, with a transport capacity of 20 tons per hour. The second subsection, 300 m long with a steep slope, could carry 150 t/h. From the cargo warehouse to the basements of the ships the ore was transported by a belt.

The system was in operation from 1908 to 1925, when there were no major activities. He was finally suspended. However, according to researchers Beatriz Herreras and Josune Zaldua, who have carried out a historical study of the Malla-Arri and Asteasu mine, "the legacy of this activity is of great value. In fact, the loader tracks are unique in Gipuzkoa and live up to similar ones existing in Bizkaia."

In fact, in Bizkaia the loaders were much more important, where the most important mines were located. According to Haizea Uribelarrea of the Mining Museum of Bizkaia, mining activity has always existed in Bizkaia, but it has been II. At the end of the carlistada (1876), losing his strength. In fact, until then only the Biscayans extracted ore from the mines, according to the forces, but thereafter the foreign capital, especially the British, was introduced and mining associations arose between the British and Biscayans.

The rich of Bizkaia...

In England the Bessemer kiln was invented in 1856 to convert iron into steel. This oven was much more efficient than the rest, and what the other converters did in eight hours did in twenty minutes. This meant a revolution in steel making it possible to produce more and less steel than anyone else. But for this purpose the mineral should not contain phosphates, and the mineral of Bizkaia meets this requirement. In addition, the proximity of mines to the coast and rivers facilitates transport.

According to Uribelarrea, "all this led to the development of mining and, with it, great social and political changes took place. First, infrastructures and means of transport were built, hence the train that passes through Trapagaran. From a social point of view, a lot of immigrants came to work, cities emerged and a new social level, the bourgeoisie, was created."

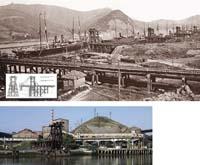

The transformation of the Bilbao estuary is also an exponent of this era. To introduce the mineral extracted from the mines on board, between the mouth of the Cadagua and the beach located in Sestao, numerous shippers were built, which between 1880 and 1903 dragged the estuary and modified the route to facilitate its transport.

Before loading, the mining stones were transported in baskets of 40-50 kilos to the coast. Normally the women did this work and in 12 hours they loaded about 200 tons.

When the industry gained strength, they had to improve the system to make the process more efficient and economical. The initial loaders were creosoted wooden boards, placed in slope and in two directions: on the one hand came the cars loaded with minerals and, after the manual overturn, returned empty. The ore fell from a hopper to a canal and slid through it to the basement of the ship. In each loading yard of the Bilbao estuary they could load 1,600 tons in a day.

As the size of the boats increased, they had to introduce improvements in the system, since the ships could not approach the coast because the depth was insufficient. Thus, cantilever bridges were built. These bridges were metal structures with two supports, one central on one column and one on the anchorage. The other side went out over the sea from 25 to 35 meters and by it the mining stone entered the boat. Although the mineral stone was initially carried in wagons, conveyor belts were subsequently used.

As on the coast, in the estuary

One of the examples of this evolution is that of Pobeña. There was built one of the first shippers with wing towards the sea, El Castillo, in 1907. Previously there was another one made in 1882, more basic, that carried the ore in wagons from the warehouses to the basement of the boat. In particular, minerals were loaded from the mines of Kobaron and Karraskale, located 3 kilometers from the coast, from where the ore was transported by train.

With the expansion of the activity it was decided to build a new structure. Attached to the warehouse mouths, supported by two towers, two load levels of 57 meters long were placed that were used simultaneously. The ore was poured directly on board via conveyor belts. Between them they could load 1,700 tons of ore per hour. Thus, for four hours a ship of 4,000 tons was loaded.

The evolution of the other Bizkaia loaders was similar. However, not all were on the coast; in the estuary there were also many shippers. It was an ideal place for cargo, since everything was present: mines, industry and means of transport, that is, the train and water. Of those that remain today, Uribelarre of the Mining Museum of Bizkaia highlights that of Orkonera: "Also known as the English bridge, it was in operation until 1986."

Although only one remains remain, five were built in 1877. In them the mineral from Somorrostro was loaded by train. They had a solid wood structure and two heights to fit the tides. Over time they were renewed and improved, for example, in the late 1920s a metal structure was built. On the bridge of the English you can still see this structure and other elements like pulleys. On the contrary, the mobile platform that at the end of the cargo operations was removed to facilitate the manoeuvre of the ship has disappeared.

Last witness

At present there is a single loader that maintains the entire structure, not in Bizkaia, but in Cantabria. Cargadero de Dícico, with the name of Bien Cultural. Like the rest, over time it was transformed and renewed. This loader, belonging to the company Iron Ore, was built for the loading of the ore of the mine of the Dícico. The initial, basic, was built in 1882 and replaced in 1896 by a cantilever bridge.

It worked until the Civil War. In August 1937 the Republicans destroyed it with dynamite, but in June 1938 they managed to resume it. The Blast Furnaces of Vizcaya and the Baskonia companies were responsible for the reconstruction, since they were members of the mine, and although in part they maintained the structure of the previous one, they made some reforms. However, gradually the activity was decreasing and in the 1970s it was suspended. It was the end of a time.