Belief: self-augmented reality

Belief has been considered a disorder of the senses. However, according to Dr. Helena Melero Carrasco, it is not a confusion, but a way of perceiving the environment and oneself. This was defined in an article published in Revista de Neurología in 2015: “Belief is a neurological phenomenon in which the stimulation of a sense causes perception in a sensory system that has not been directly stimulated.” Melero is synesthetic and made a thesis on this phenomenon in the Department of Psychobiology of the Complutense University of Madrid.

With him coincides the neuroscience professor Pablo Barrecheguren Manero of the University of Barcelona: “It must be made clear that it is not a pathology. There are people who, besides believing, have suffered mental alterations. For example, when Vincent Van Gogh began to learn to play the piano, he related the notes with certain colors; his teacher took him crazy and threw him. This anecdote shows a synaesthetic perception, but with a bipolar character, such as psychotic crises and alcohol dependence. Perhaps for this kind of cases some think that belief is a confusion.”

For Barrechegune, therefore, it is important to analyze the belief and to socialize well the explanations to “eliminate false convictions”. But not only for that: “The investigation of synaesthesia gives us indications of a better knowledge of the senses, and from that knowledge can arise new ways to overcome the inadequacies of sensory systems”.

For example, Santiago Eloy Alfaro Bernat has developed a technology system that allows people with some reduced sense to access information about the environment through direct access to the brain. Digital Synesthesia, that is, digital synaesthesia.

A world of its own

Miren Karmele Gómez Garmendia is synaesthetic and for her it is nothing special: “By comparing my way of perceiving reality with what others say I realize that mine is different, but for me it is normal.”

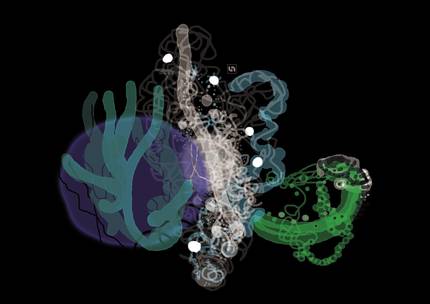

He describes with great precision his experiences. “For me all sound has a color, a form and a movement. It also has texture, and all this I see on black background. And I see it in the source of sound, that is, if the sound comes back to me, I see it behind me, although I don’t have eyes behind my head,” he says smiling. “And behind all this I see what others see. I see all the sounds in different planes and I also see my voice, and I do not get confused, because it is hierarchized. For example, you listen to me and at the same time you hear the sound that surrounds you. For it is similar to me, because I have always had this way of listening and seeing.”

Gómez has nailed to the head who, as a child, told him that he was an “imaginative” girl. At the time he studied in Bilbao he realized that he had another way of perceiving reality, differentiated from the rest: “I told my roommate that on that day the bridge changed color and, in response, I realized that not everyone saw things like me. Furthermore, he suggested that it could be a belief that he was the same roommate.”

Since then, he is aware that he sees the environment unlike others. At first, he needed time to realize that he had something that separated him from others and to know what we see and what he sees only. “Now I live it normally and I know that I see a layer that is mine.”

Ten years ago, based on this layer, he began to create drawings, first from words and after songs. Now he also draws sounds from a concrete moment of everyday life: “It’s as if they were synesthetic photos that gather what I see at a given moment.”

For him his perception is so strong that when he realized that he was surprised that not all the aesthetics perceive things the same. “For me the vowels have color: a is white, and green, i yellow, or red-brown and u blue. Because I met another person with that same kind of belief. I was surprised when I knew that for him the vowels had another color.”

It is not so rare

In fact, according to many studies, the most frequent type of belief is the visualization of color graffiti. After Melero last year, he occupies second place after the spatial sequence. Melero distinguishes the spatial sequence in two types: that the numbers have a spatial configuration and that the time has a spatial configuration. And Gómez also has that kind of belief. In his words, he sees the time placed in space, in a very graphic way: “The year is an oval; the weeks, long pictures, and the day, a line that comes from top to bottom.”

In Melero's research, 13.95% of participants were synaesthetic, with no differences between right or left according to sex, age or learning. In other studies, the percentage of synesthetics ranges from 0.05% to 23%. To explain why the difference is so great, Melero believes it will be a way to investigate. He was a consultant and did so in faculties, work centers and network. He wondered about the type of belief and only took into account those who “always” had that experience.

Among the most common types of beliefs is the one that relates sounds and colors. It should be noted that those who have a type of belief tend to have more, as confirmed by Melero's study. Within the belief that a sound stimulus makes you see color, there is sound as musical. In the classification of Melero, the type of belief that produces color can be of three types: the one that joins the tone with the color, the one that joins the chord and the one that depends on the instrument.

In other types other senses intervene: to see and smell something; or to hear it has smell; or to touch or hear it has flavor... And in addition to the relationships between the senses, there are others such as letters or numbers being of a given genre or being personified.

Sensations of colors

Sensations and emotions can also be the motor of the synaesthetic experiences. In the classification of Melero you can see in colors all perceptions: touch, pain, temperature, nature, flavor, smell, emotion and orgasm.

These last two are the lives of Leire Alberdi Arriola. He says he has recently realized that he is synaesthetic: “After reading and commenting on an article on belief, a friend recommended seeing a documentary on the subject and then I started to make ties. And it’s that until then I didn’t talk much about it, but, for example, when I told my partner that orgasms were dark blue or orange, I caught in the joke.”

In addition to orgasm, she lives some emotions in color. “They have to be strong emotions, not joys and sorrows that we have on a daily basis. For example, I've had two nearby deaths, one of them especially exciting for me, and it was green-turquoise. Remembering with the other, that color comes to my head.” He explained that “they are always solid colors, tones that can be defined well: yellow, oranges, turquoise, granates... Usually they are repeated and the intensity can vary, as if they were painted with watercolor, but I have never felt pastel colors, marbling or indefinite. And they have movement, a movement similar to a curtain or hot water.”

Some people are also color agents but have no movement. And although it relates emotions and people with colors, the link is unidirectional, that is, color does not generate emotion. For example, yellow is related to a critical moment of life, the moment when it was about to leave the studies of Fine Arts. “It was a tough time of crisis, but then the yellow color doesn’t transmit that to me. What’s more, it’s one of my favorites.” The investigations confirm this, that is, that the synaesthetic experience is unidirectional.

Finally, in addition to the colors, Alberdi added that when touching the metallic tools it feels a flavor or texture in the mouth.

Genetics and development

In addition to the characteristics and types of belief, scientists have investigated the origin of this phenomenon. Apparently, it has a genetic base and is hereditary. There are studies that show that in women it is more widespread than in men, so some have considered it may be related to the X chromosome. However, it has not been demonstrated and the research of Helena Melero has not confirmed this hypothesis either, since among those who responded to the questionnaire there were no differences by sex.

Regardless of the genetic variable, researchers believe it is related to the processes that occur in brain development. This is what Barrechegune explains: “When we are 10-12 years old, a process called neuronal pruning occurs. Through this process, the brain removes from a lot of neuronal connections made so far, which it does not use. At that time, therefore, what it uses and works is reinforced and much of what it does not use is lost.”

What happens then in the case of belief? “The children’s brain creates many connections between different zones, and some seem to have synesthetic experiences. But then, when neuronal pruning occurs, some of these children lose their sinesthetic characteristic, but others are not sinesthetic that remain adults,” explains Barrechegune. They are, therefore, sinestésicas, like Gómez and Alberdi, which have maintained this childish peculiarity.