Creation of the scientific method

XVII. In the first third of the 20th century we have seen two big names: Kepler and Galileo. The steps taken at that time prompted science on paths without return. What in 1630 was but an effort, would materialize shortly, that is, the laws were published to mathematically express the functioning of the universe (as something complete or its parts), combining cosmology and physics.

The dynamics of Galileo, with which the movement, axis of the new physics, would imply the mechanical understanding of cosmo itself. Among other things, the responsibility lay with a scientist, Newton. The world would become a watch machine. But for this to happen we had to make a revolution (the scientific revolution) and in that work two other big names appear to us: René Descartes and Francis Bacon.

At that time, XVII. At the beginning of the 20th century, the capital accumulated in the shipping environment was used in manufactures. The capitalist installed in a single factory workers from the various departments previously dispersed, beginning the division of labor. The product obtained was not the result of a person as before, but of a group. Productivity increased, better tools were made and, incidentally, more special, losing importance to manual dexterity that was previously highly appreciated.

The production process was divided and each of the levels of this chain could be performed by almost anyone. Bacon and Descartes knew that atmosphere of change. Both rejected the speculative conception of science and knowledge, defending that science should be at the service of man. Science, among other things, had to lighten the workload by making man the head of Nature.

As a result of this change in the world of work, Bacon and Descartes saw the need for collaboration between different sages. That is why they related to Mersenne, Huygens, Beeckmann and others.

New conceptions of science and philosophy clashed with the official knowledge of the time, syllogism, personal genius and the argument of authority. When these two men agitated the sterile psychological apparatus of the scholastics, marginalized in the universities, it became a barrier to the development of society in which the whole conception of science and philosophy was being drilled, and with it a vision of the world. The bourgeoisie needed the support of experimental science to strengthen itself (Bacon) and its clear and comprehensive foundations (Descartes).

In that environment, how were the relations of these two men with the Church? Bacon was more fortunate than Descartes. He did his job in England, where they were carrying out religious reform. Descartes, for his part, was in France and had to suffer the strong attacks of the Church. Despite efforts to demonstrate the existence of God through reason and to base metaphysics on physics, he was denounced as an atheist and included his works in the Index. Bacon loudly claimed the difference between the discovery of nature and that of God, and although he encouraged the development of the former, he claimed that God's truth should be accepted without criticism as it appears in the Bible.

Descartes, for his part, claimed that there were two substances that have nothing to do with each other: one material (extensive res) and another spiritual (res cogitans). Thanks to this, since then scientists could carry out their first works with little religious barriers, provided they did not enter the religious sphere. Despite its advantages, it also had a negative part, that is, the works of Descartes generated the problem of dividing the world into two levels: material and spiritual.

The confrontation of these two levels led to the creation of a type of man who still exists in the world of science: a scientist who believes he does not participate in religious problems or politicians.

Francis Bacon was born on January 22, 1561 at York House, next to London. Son of a good family, he studied at Trinity College in Cambridge. He later moved to Gray’s Inn to study law and traveled two and a half years before finishing. During his studies he met Paris, Blois, Poitiers... exploring museums and libraries. Back in England, after law studies he worked as a lawyer and was appointed a parliamentarian. However, although his craft was the other, he immersed himself in the world of knowledge and in 1605 he wrote two books under the name of Of the proficience of Advancement of Learning.

While the first speaks of the advantage that knowledge has for kings and politicians, the second is about the errors of the wisdom of the time and how he directed them. Then, when he was at the top of his political activity, he wrote the book entitled Instauratio Magna. The work had to have six sections, but the only one published was the second, Novum Organum. In 1621, he was expelled from all his charges. Retired to his home in Gorhambury, he devoted himself to research and writing.

This man has been very much discussed. We must recognize that he was not an experimental scientist. It is useless to seek some law or theorem that bears his name and it is true that it is also out of the great achievements of the science of his time. For example, Copernicus, Kepler or Galileo did not know or discard works. When he approached one particular science or another, he had a previous attitude to Galileo. So what is the result of this man? He clearly indicated his objective: To serve Humanity with new light on nature.

And he perfectly fulfilled this objective by becoming a defender of the new science and claiming the criterion of the function of science that we all recognize today, that is, that the objective of science is not to find metaphysical truths about the nature of things, but to achieve paths that increase and enhance human power over nature. For this he faced several opinions in force in his day. Think of the XVI. At the end of the 20th century in England official knowledge was also scholastic and that was a conservative philosophy. In Bacon, against him and against Aristotle, known as the miserable sophist, he fought hard. He rejected the contemplative philosophy and affirmed that the practical results of natural philosophy not only served the welfare of man, but also to guarantee the truth.

After Bacon discovered that those who made inventions and discoveries were artisans, in most cases they were scarce, poor and limited. He thought that the way to improve this situation was the union between industry and science. The short vision of craftsmen could be improved through science, that is, theory. To do this, science had to be completely reorganized and thought that the best way was to make an encyclopedia about nature and the arts.

But for one friend it was impossible. Many men and from different countries would be needed. For this reason, his Constitution, to which we have referred before, dedicated it to King Jakob I. In his day he did not get that dream, but years later, specifically in 1662, the Royal Society (in part) was launched in London to make Bacon's ideas a reality. Therefore, we must say that Bacon opened the way without cultivating science itself.

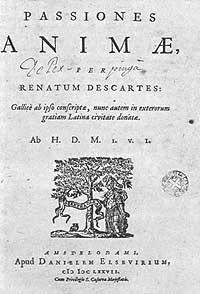

Following this path, the other name we mentioned above has been René Descartes (1596-1650). He was born in La Haye-en-Touraine. He was a good family and studied at the Jesuits, but his most prolific work he did for twenty years in Holland. Descartes laid the foundations of modern critical philosophy and opened up some new mathematical pathways useful for the physical sciences.

In many of the ideas that were accepted in the field of philosophy without discussing at that time, implicitly introduced without contrasting, there were many advances that he made public. He wanted to build a new theory from the ground up. The essence of this theory would be none other than human consciousness and experience, which sought from the mental creation of the idea of God to observation and experimentation in the physical world.

In the field of mathematics, Descartes took a big step. Developing existing ideas in ancient Hindus, Greeks and Arabs, he adapted algebraic processes to geometry. Until he did, to solve any geometric problem he had to use a special skill. Descartes invented the concept of coordinates. Therefore, once taken two coordered axes (x and y), we can express the position of a point (in the plane) by two numbers and by their formulas many geometric figures (straight, ellipse, parabola, etc.) we can express. If formula is available, the geometric problems could be posed by algebraic equations and once solved the results can be read geometrically. In this way the solution of many still insoluble problems was achieved.

Descartes revealed the importance of the concept we know today as energy as the work of a force. After all, I thought that physics was a set of mechanisms and that the human body would be one of them. At that time Harvey accepted what was said about the circulation of blood (which said it circulated through the veins and arteries) and in the debate that arose he favored it. However, in his view, the cause of circulation was not the heartbeat.

In his opinion, the cause of the operation of the human machine was in the heat that was produced in the heart through natural processes. Therefore, the rational soul and the governing body to keep him alive were two completely different realities. So, and as we have said before, Descartes is the first thinker for all dualism and established a strong boundary between soul and body or between mind and matter.

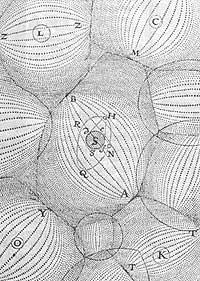

Descartes tried to investigate phenomena to improve the known principles of terrestrial mechanics and it seems that at this point, although his fundamental philosophical attitude was the other, it was based on the Greek-scholastic ideas of antithesis. He confronted the world of matter with that of spirit. Spirits are personal and discontinuous. Therefore, matter will be impersonal and continuous: its essence must have extension. The physical universe must form something closed and full, there is no empty space.

The only way to make a body move in this world is the contact it can have with another, and that happens in closed circuits; there is no vacuum to pass through there. Hence, Descartes extracted the theory of swirls that occur in a totally spacious and undivisible ether. Thus, as a straw floating in the water attracts to its center the whirlpool of water, the Earth attracts the stone that falls on it or the planets attract their satellites. Meanwhile the Earth and planets creep around the Sun in another major whirlpool.

Years later, Newton showed that Descartes' turbulence did not conform to observations, but in his day he achieved great fame. Limiting the terrible problem of kneading to dynamic laws was a courageous attempt that, from this perspective, proposed the history of scientific thought. In fact, he regarded the physical universe as a great machine and therefore its functioning could be expressed mathematically. For the contemporaries of Descartes his swirls were much more understandable, since the movement was transmitted through contact and not through forces that, according to Galileo, distanced.

According to Descartes' theory, initially God gave movement to the universe and then abandoned it by himself, although he moved by his will. The universe that Descartes tells us is more material than spiritual and more indifferent than theological. God has gone from being Total Good to being First Cause.

Descartes, according to Galileo, thought that the primary qualities (predominantly of the extension) are mathematical realities and that the other qualities are nothing more than the transpositions that our senses perceive. However, in his opinion, the same mentality is as real as matter. Thus, Descartes came to dualism: at one end is the world of bodies and at the other the world of thought: rex extensive rex versus cogitans. Matter itself is totally dead and its activity is nothing more than the movement God gave it at first. In fact, Descartes at one end of his dualism is a mere materialist, since he considers that the fractions of matter have no logic of life.

This dualism poses the problem of the relationship between two quantities that apparently have nothing to do with intelligence and matter. In an expanded and material world, how can uneducated and immaterial intelligence influence? How can they produce immaterial sensations? Descartes said about it: Because God formed things like this.

Descartes' sense extended to all areas of knowledge: philosophy, psychology, methodology, astronomy, mechanics, mathematics, optics, etc. In some areas, such as mathematics, his ideas have remained firm. On other occasions, he has taught us that futures were guilty. However, Descartes, along with Bacon, is the forerunner of a new methodology that would guide the new science.