Lezetxiki and his ancestors

Many things have happened since the Barandiaran group stopped digging Lezetxiki. It can almost be said that nothing is like in those times. In fact, the environment of this site, located next to Arrasate, has changed a lot. The Labeko Cave, located four kilometers away, does not exist today. And not only have places changed, but also people and technology.

Parallel to this evolution, there have been two major changes in European prehistoric research. On the one hand, it has been a great technological advance, with techniques and tools that forty years ago could not be imagined. On the other hand, the deposits discovered in recent decades have shaken the perspective of the prehistoric population.

Around Atapuerca

During this time, that is, since Barandiarán and his team stopped digging, paleoanthropologists have discovered new species of hominids and have proliferated human remains and researched deposits. Among them are the deposits of Atapuerca, systematically excavated from the 80s. It is located about ten kilometers from the city of Burgos, in a karst mountain range decorated with Mediterranean forests. Along with other vestiges, the finding has modified the perspective of European prehistory.

Atapuerca and Lezetxiki have a strong relationship. No wonder they are located in the natural passage that connects the European continent with the plateau of the Iberian peninsula. Therefore, every population movement has passed through these places. In addition, this gateway is not only a prehistoric issue, but in many other times it has been a basic path. For example, in the Middle Ages pilgrims traveled the Jacobean route, so the most used Jacobean route today is in this area to go from Logroño to Burgos. The use of this pathway is also reflected in today's media.

In addition, in prehistory, the populations from Europe found in the mountains of Euskal Herria and in the surroundings of Burgos suitable caves for their protection (and Lezetxiki was one of them). This means that any human species found in one of these deposits would probably be the other. Although this concept is evident, it has a great importance for the correct interpretation of the traces of Lezetxiki for its relationship with the deposits of the area.

Appearance of the cave

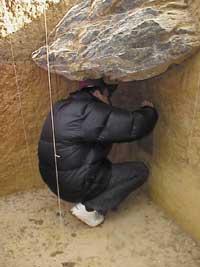

Lezetxiki is a natural tunnel formed in the mountains of Arrasate. However, before continuing the description, it should be noted that the mountains are not fixed or immobile structures. However, over time, these large rocky masses move, bend and break.

This has occurred in Lezetxiki (and is still happening) and is well appreciated in the tunnel structure. As a result of this mountainous activity, the roof of the exit to the south has been falling, so gradually the tunnel has become shorter. And so, with the passage of time, the southern portico has been "delayed" and, in turn, the humans and animals that inhabit it have been leaving their traces more and more to the north. It should be noted that most of the activity of these caves was developed in the portico. And all this conditions the organization of research: as researchers dig north, they find increasingly modern clues.

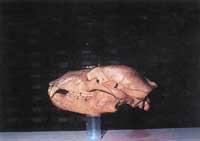

However, the cave is not formed by a single tunnel. During the investigation of the Barandiarán group, a researcher named Leibar discovered another branch of the cave. Since then it is called Leibar Valley. There they discovered, in 1965, the oldest human fossil in the Basque Country known for the moment: a complete humerus.

In the excavation campaign of recent years, researchers work in another cave. It is not clear whether this cave (called Lezetxiki II) is related to the main tunnel. It seems that it ends in the Leibar branch, but it will not be known until an excavation of about four meters is executed, which could last approximately four years.

Three questions, two answers

Researchers currently engaged in excavation are hopeful that the cave of Lezetxiki II retains some answers. If they are not mistaken, Lezetxiki II and Leibar meet at the place where that famous humerus was discovered, and if this is so, to understand the origin of the humerus, it is necessary to study the layers of Lezetxiki II, which are not yet excavated.

Taking hope further, there may be other human fossils in the vicinity of the encounter of both caves. This hypothesis is not exaggerated, because finding only a complete humer is something very curious in Paleoanthropology. Where are the other bones of the same body? If there were none, why has the humerus remained complete?

Therefore, researchers have asked three questions: Are Leibar and Lezetxiki II related? Is there a stratigraphic level directly related to humerus? Will other bones of the same human being appear? Surely the first two questions must answer yes. But at the end, at the moment, there is no answer. We will have to wait.

However, Lezetxiki II is not the only point of study of researchers in this field. The Barandiarán group continues to work around the excavated section, on the mobile portal south of the main tunnel. Numerous remains of fauna are being extracted, accompanied by numerous stone tools, not only work tools and weapons, but also 'symbolic' objects that have been unearthed. Scientists have found decorative elements with shells, among others.

According to suspicion, these ornaments were not of the man of Cro-Magnon, which has interpretative consequences, since the remains found in Lezetxiki can be evidence against hypotheses that question the intellectual capacity of Neanderthal (or of previous humans). This type of interpretation is increasingly accepted in paleoanthropology.

Conservatives of tradition

The site is therefore interesting, both for its location and for its localizability, as well as for its implications in the context of European prehistory. However, excavation and research are not quick, as they present great obstacles.

On the one hand, archaeological work is in itself slow; it is an activity that requires very precise planning and requires special care to achieve reliable conclusions. Archaeologists, anthropologists, paleontologists, zoologists, palenologists, geologists and other experts work at the site. On the other hand, in administration it is not considered science such research, but human science. Therefore, it has few grants, much less than any other scientific research receives. Lezetxiki employs some of the best professionals in the world and, according to project managers, their budget does not correspond to the degree of interest of research.

Lezetxiki Working Group

- Geochronology (ESR, Uranium/Thorium, TL): Christophe Falgueres Helène Valladas Norbert Mercier

- Sedimentology: Related information

- Micromorphology: Josep Vallverdú Marie-Agnès Courty

- Archaeozoology: Jesus Altuna Koro Mariezkurrena Eduardo Pem·n Mikelo Elorza

- Palinology: Technical service

- Antraquology: Related information

- Equipment: Alvaro Arrizabalaga