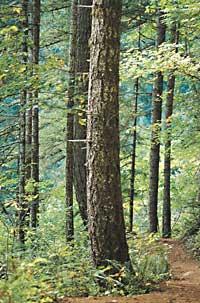

Forests as a mountain workshop

The surprise of going to ask is that this forest is not, in any case, the one that would have been left unexploited. And it is that natural forestry, despite being so called, is not one that has no human intervention. Yes, however, forestry supports the conservation of wild plants and animals that tries to imitate the structure of natural forests. The new trees come from seeds of adult specimens present in the forest.

In natural forestry, the diversity of forest functions, i.e. the ecological, social and economic function, is well fulfilled. Therefore, this beech does not seem to be an example of natural forest activity. Nice yes, economic and social, but not ecological, totally homogeneous, monospecific and without scrub.

In artificial forestry, on the other hand, the communities of living beings vary considerably, all the trees are of the same age and their cycle ends when they reach the short time, that is, the new plants do not come from native seeds, they are planted. In addition, artificial forestry, in most cases, forgets the functions of the forest and uses a purely economist perspective, considering only the exploitation of wood.

Many of the beech trees that were part of our myth are exploited from a purely economic point of view, are artificial, although native species are used and in the plant arise from seeds. However, there are intermediate situations in natural and artificial forestry.

Forest techniques

In general, forestry techniques can be grouped into two groups: the techniques in which all trees are demolished on land or plots and the techniques of entresacas or clareos. The use of one or the other depends on the species to be exploited, the physical environment and the objectives pursued.

One of the techniques is the expulsion of all trees from a certain plantation and the deforestation of the soil, known as matarrasa. Once all the trees of economic value are cut down, whenever possible heavy machines are used to eliminate the rest of the vegetation and stumps. In these cases the top layer of the soil is also removed or at least raised. When heavy machines are not possible, clearing is done manually and the top layer of the ground is not so damaged.

It is a very intensive technique. In Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa it is used in pinares insignis, whenever possible by heavy machines. In the Alava and Navarrese beech forests and in some sections of the northern beech of Irati, in the red pine forests of Álava and Navarra, and when the pine insignis is in very steep places, it proceeds to the demolition of all the trees and the elimination of the rest of the vegetation, but manually, not raising land or cutting.

In addition, in the forests of beech and red pines, it is often not necessary to plant trees, since the seeds of the earth germinate new plants. Thus arise the “wonderful” beech trees that are observed in different parts of Navarre; the underlying net – everything that has no economic value – and the ‘lean’ beech of the same age. They are ecologically quite poor, often poorer than pinares insignis.

In the case of eucalyptus it is not usually necessary to plant new plants, since it is easy to give new shoots of stumps, at least three times. Both in plants from the seed and in the case of eucalyptus sprouts, the grains are isolated as they grow.

The technique of matarrasa has advantages from the point of view of exploitation: all trees are the same age and in times of growth it is easier to carry out work in the forest, since many of the works are done mechanically saving labor and money. It is the most profitable form of exploitation, especially when growing foreign, allochthonous species, in which no other forestry function is normally contemplated.

But it also has ecological disadvantages, especially: the top layer of the earth is lost due to the withdrawal of the machine or rain; all other plants and dead organic matter are eliminated; and completely monospecific forests are formed, wooded of the same age and without old trees (both pine and beech). As a result, the richest soil layer in organic matter is lost and erosion is increased, forest structural diversity is lost and biodiversity is lost. In addition, in the long term, after several cycles, it can become landless or exhausted.

Currently the law prohibits the use of heavy machines on slopes above 45-50 degrees and land lifting.

The other group of techniques is through entresacas or entresacas. This is a more extensive form of exploitation but with different levels of intensity.

In some cases only trees of a certain age and structure are cut. The gap left by the downed woodland gives rise to the germination of new trees, so the forests thus exploited have a relatively high structural diversity, as they include trees and bushes of different ages. It is one of the least pressured farms, so it is one of the most suitable from the ecological point of view, but also the most expensive from the point of view exclusively of the exploitation of wood. In Euskal Herria there are hardly any such exploited forests.

Another way to make the clears is to cut the trees by plantations, but never all together. Some trees are deposited from the plantation to give seeds and from them new trees are created. When the forest is exploited in this way, maximum 90% of the trees of the plantation are poured, depending on their suitability. Consequently, plantations with trees of different ages are created in the forest and minimal structural diversity is maintained in the forest, even by departments. Countless new trees grow in the forest, all of them very narrow.

Over the years they are isolated and left the best for trees. In Navarre, for example, many beech trees are exploited.

History and influence of property

The historical causes (mainly disamortizations and population density) have led us to the current situation. But history, history, the current situation, has much to do with forest management. In Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa private property predominates, while in Gipuzkoa, for example, more than 80% of private owners have pine forests under two hectares. The average forest area of ACBC individuals is 8.5 ha. This greatly hinders the management of valleys, counties or other large areas: each owner acts on his own and it is almost impossible to consider in the mountains a criterion different from economic. Currently, forest harvesting plans are mandatory in some territories, but only in those over 20 ha.

However, some of the Alava forests and most of those of Iparralde and Navarra are forests of public use and of greater extension. As a result, they offer more management possibilities and allow more ecologically appropriate forms of management, taking into account the functional diversity of forests.

In addition to the influence of different techniques on biodiversity and land, there is another topic that gives a lot to see: mountain tracks. More tracks are normally made and used on intensive farms. In addition, when the exploited plantations are small, as in Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, the number of tracks increases considerably, since each department does the same. When the tracks are in good condition and constitute a planned and adequate network, they can be very useful for forestry, fire fighting, etc.

Many times, however, they do not meet these conditions and can cause problems such as diverting water and its conversion into erosion points, facilitating excessive entry of vehicles or fragmentation of the land, among others.

Finland and Canada

It is not, of course, the only country operating in the Basque forestry sector. There are also many forestry models, but there are models that are heard many times when talking about forestry. Among the exploiters of allochthonous species, New Zealand and Chile cultivate pine insignis that are the main competitors of the Basque insignis.

Seeds from those countries are also used for cultivation and, incidentally, for increasing genetic diversity. The maritime pine of the campas also competes strongly with pine wood of the lowest quality in the country. All of them use an intensive method of forest exploitation, the matarrasa, in which the economic point of view predominates in the pinares insignis. As in the famous pine forests of Euskal Herria.

On the other hand, Canada and northern European countries, such as Finland, are large producers of wood. Native species are used in the latter, although very intensive forms of exploitation usually predominate. However, the exploitation of native species allows them to take into account ecological points of view, as occurs in Navarre with beech trees, but not with wild pine forests.

In Finland, for example, plantations of less than two hectares are simplified, resembling pine farms in the Basque Country. After deforestation, they plough the land, which is a very flat country. Then, sometimes, like the Navarrese beech, they leave some trees for planting and others plant them or take advantage of the seeds of the adjacent trees, depending on the species.

However, on many occasions, all dead or corrupt logs are abandoned. Once the new trees are reinforced, they eliminate the vegetation in the area to reduce competition. A few years later they made the first cuttings, but depending on the characteristics of the land: in the poorest lands only pine trees and in the richest, fir and leafy. Occasionally they leave areas of special ecological value untapped.

In Canada the operation is very intensive and takes place on large areas. However, in areas close to roads and villages, smaller scratches have begun to be built to minimize visual impact. And there is another difference: Canada has 309.8 million hectares of forests. Of these, 294.7 million are not protected, so they are exploitable. However, there are 144.6 million hectares ‘only’ accessible, that is, exploitable. And of all these, about a million hectares annually, approximately the forest area of the French Landes. Compared to the extremely reduced surface, it allows, if well planned, to do things in order.

Radiata pine

- Originally from central California. Currently only appears in nature in three areas: San Mateo and Santa Cruz, Monterrey and San Luis Obispo. It does not form large wooded masses itself, and is also protected in some places. XIX. The Marquis of Adam of Yarza planted his first pines in Lekeitio in the late twentieth century. At present it is the most exploited species in Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, and the most widespread on the surface. In the Bajo Deba and in the Plentzia-Mungia line are the best quality forests, below 500-600 meters, the poorest east of Gipuzkoa and south of Bizkaia. 20 years ago most of the pine was intended for bins, often cut at 20-25 years. Today pine wood is the most sent to sawmills, which is thrown at 35-40 years to obtain larger diameters. Some owners also prune and care more because wood with fewer patches has better quality and therefore sells more expensive. In 1982 a genetic improvement program was launched. The 80 most productive pines were selected, from which genetic improvement began, both with the production of shoots and with cloning. Subsequently, a second selection was made in which the healthiest pines were included to increase resistance to diseases and pests. They also investigate the treatments and new uses of pine wood. New Zealand, Chile, Australia, South Africa, Euskal Herria and northern Portugal are the main producers of insinis. In general, the pine forests have a smaller diversity of birds than the oak trees, although their density is higher. Plant diversity is also lower.

Certified wood Labels and certificates are seen in many products as quality indicators. And wood also has its own, to put it more correctly:

The promoters of the FSC certification claim that the PEFC criteria are more agile and that, to a large extent, it is a discredit to deal with the added value that the FSC was obtaining. On the contrary, those who promote PEFC say that FSC responds to environmental criteria, it can be useful for developing countries, but it does not adapt to a situation like Europe. |