Intelligence, why?

Apparently, Homo sapiens does not seem to be the best candidate to dominate the world. Our body is poor and defenseless, without “tools” of large predators. But no matter, the key to our ‘success’ is not strength, but the brain. That is why we tend to give value to creativity and the ability to learn complex things that are so ours and that are the point of evolution.

However, if our kind of intelligence is so good, why is it the only one in nature? Evolution counts on about 3,500 million years, time in which one can think that some other living would have the same ‘winning formula’. But our great brain is an exception in nature, something unusual. Most animals adapt very well to the small brain and to the learning capacity that seems limited. Therefore, perhaps the combination of the great brain and advanced intelligence is not necessarily the winning card in the lottery of evolution, but the simple evolutionary adaptation.

In the investigations and debates on the subject, many ideas and theories have been published. For example, it is often better to have little intelligence. Or that in all cases in which intelligence has been developed it is possible that it has developed at the expense of strong losers and not thanks to successful individuals.

Intelligence is expensive

Being able to learn is essential in what we call intelligent behavior. Thus, it is logical to think that a great learning capacity is of great utility, but that is not at all a universal standard. Many animals learn from other animals (macaques learn in other ways that have to be more frightened with snakes than with flowers). But animals who instinctively know which predators should avoid, what they have to eat, or how their mother is are less vulnerable than those who have to learn. It takes time to learn and runs the risk of making mistakes.

Learning has unavoidable costs. The brain is one of the tissues of the body that needs more energy. Ours needs 20% of the basic metabolism, while the lower brain mammal needs 3%.

To this we must add the cost of protecting this sensitive structure, that is, the robust skull, the differentiated regulation of temperature and adaptations to precisely control the chemical conditions of the brain. In addition, the great clergy need more time to develop, so parents must devote more time and energy to the fecundation and growth of descendants. All of them can present reproductive disadvantages against competitors of lower horizon.

All this is difficult to prove experimentally, but there is a new research that explains the reasons why many species remain with less intelligence. In Switzerland they have managed to grow fruit flies faster than normal. For this purpose, they fed gelatin made with orange flour and pineapple flour, but one of them was added quinine of acid flavor and others was removed. Playing with these foods and controlling fertility, over 20 generations they have shown a greater learning capacity of these flies.

However, they are not superflies, or anything like this: in other fields where it is not to study, traditional flies predominate, the 'dumb meshes'. For example, fast fly larvae are shaped worse when there is little food. Therefore, the increase in learning capacity can increase the survival of individuals in some areas, but in others it decreases.

Why be smarter?

Biologists have had great interest in knowing which species have an intelligent behavior and why. Almost all agree on one point: the key is in the variability of the medium. Mathematical models show that when the medium slowly changes the best option of living beings is to respond to their instinct. But if the environment changes a little faster, the most appropriate tactic is to learn from others, that is, social learning. Finally, in the fastest changes, individual learning is the most appropriate.

Each theory and research highlights specific aspects of the variability of the environment to explain the evolution of the mind. The theory of ‘social intelligence’ is based on the advantage of brain development versus rapid changes. Intelligence helps individuals to integrate into social life and helps them collect information from others to adapt to the unexpected. The study reveals that mammals living in large social groups have a greater brain in proportion to their body size.

Other biologists focus more on physical changes in the environment, such as food distribution or the need to learn how to acquire food that is difficult to eat. It is called ‘ecological intelligence’ and it says that those who live by eating food spatially and temporarily distributed, such as fruit, have more brain than those with more widespread and safe sources of food, such as leaves.

There are researchers who say that intelligence has developed as a result of positive feedback. In his opinion, intelligent species are more recurrent in the face of new situations in which learning is an advantage, such as the tasting of new foods, which in turn generates a selection pressure, increasing the learning capacity.

Until the appearance of man, about two million years ago, cetaceans had the greatest brain of mammals in proportion to the body. Therefore, they seemed to be the ones who most predisposed to new situations, but in the last 15 million years their brain has hardly grown.

All these theories are grouped around natural selection, which may not be the only engine. There are those who say that cognitive ability has not much to do with the increase in survival and with the attraction or choice of the couple, that is, with sexual selection. The basis of this idea is that the brain is a complex and expensive structure, so the great intelligence of the couple would be associated to being a high quality individual. This would explain, for example, the wide repertoire of males of various species of birds.

Another similar explanation has been given to explain human intelligence. In many generations of our ancestors couples have preferred inventors and creatives, which has influenced the evolution of our brains. It is known that this is so in some singing birds, but in man it is still no more than a good idea.

Are animals with more brain really faster?

More and more researchers are using innovation – the invention of new models of behavior – as a measure of species creation.

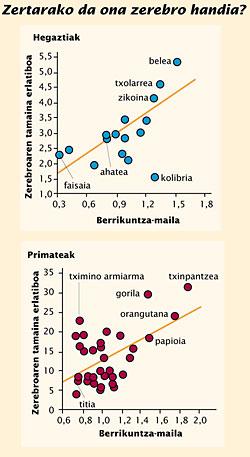

This line of research was strengthened 7 years ago when researchers from Montreal collected the publications of bird watchers and turned them into information about the capacity for innovation of birds. Subsequently, in another study the information of 116 species of primates was collected, turning each new behavior into an innovation index. The result of both research was the same: animals with a greater brain in proportion to the body are the most innovative.

It seems, therefore, that there is a direct relationship between the volume of the brain and intelligence, at least according to this index of measurement of intelligence.

But after them, they again use the work of bird watchers and investigate the influence of innovation on survival. More than 100 species of birds introduced by man in New Zealand have been analyzed and have been able to verify that the most innovative species of the original habitat have survived better in the new habitat. For these birds, at least, innovation has contributed to the port of access to the new environment.

Innovation studies demonstrate the great creative capacity of animals. Yes, many innovation actions can be explained through a simple “trial error”, without a special cognitive capacity, as well as human creativity.

The need as an engine of invention

If creativity were a universal hayedo, the lack of interest in use would seem strange. But if we see intelligence as a mere strategy to survive, it is easier to understand one's own creativity. Innovations can be beneficial, for example, to find new food sources or more efficient search techniques, but they also have cost, such as poisoning or wasting energy in something new that has no value. In humans, the use of innovations in inadequate times has caused numerous failures, including deaths.

Guppy shows that starving, small and unaggressive fish tend to be the most innovative. And in primates, the most innovative are usually those of lower social level. This, for example, does not correspond to the theory of sexual selection. In human beings, innovations often arise and are used when things have been completely complicated, but whenever possible we use already proven and proven formulas. Therefore, in the animals analyzed so far, the expression ‘motor of invention’ is useful.

Consequently, we expect that animals who use all their creative potential are of two types: those able to withstand the possible failure of their experimentation or those who, with a great need, use innovation as a final point of arrival.

In other words, perhaps the development of the creative intelligence of the human being is not a consequence of the successful innovative individuals who have wanted to do things better, but of the effort of losers not to do things so badly.

Adapted from the journal New Scientist. 17/07/1004 (pp. 35-37).