History of Abaco

As we commented at the beginning of the history of figures, before the alphabet and figures appeared, humans mainly used two accounting systems, that of notches and songs. What interests us now is that of the songs, since it is the origin of the Abbasics.

In some villages, to count the soldiers or the sheep, the songs were deposited in ditches dug into the ground; ten songs were stacked and replaced by another major stone, that is, the base ten was used. Each ditch represented a remodeling of ten. In other villages, the ditches were replaced by iron plates or wooden cuttings and perforated bowls to move through the plates or stirrups. Thus were born the ball markers.

With the word Abako we indicate three different calculators. The first, used by many ancient cultures, was the broken board or the land itself. Figures or geometric symbols could be written with a finger or wedge. In general, the Greek word abax means flat table or table without legs. Its origin could be the Hebrew word abaq, whose meaning is dust. The Hindus used this type of A.V. Until the twentieth century to make calculations with their figures.

The second type of calculator is that of tables. In these tables parallel lines were drawn indicating a numerical order. To make the numbers and calculations a few runs or chips were placed on top. To these pieces the Greeks called the psehones and the Calculi Romans. These lines could be traced on parchments, carved in marble, carved in wood or embroidered in fabrics.

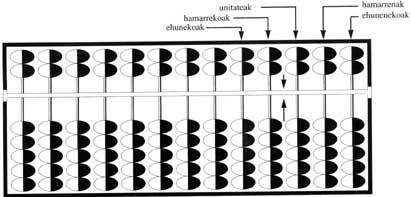

In the Abbasics of Rome, each column (or row) represented a recomposition of ten; from right to left and beginning with the units. Sometimes the column was divided into two parts. At the bottom a tile indicated a unit of the corresponding order. At the top, however, a tile was worth half a unit of the following order (or five units of the corresponding order). This is in the first column 5, in the second 50, etc.

In a bas-relief of a 1st century Roman sarcophagus, a young calculator, with accounts in the houses of wholesalers, can be seen before his master with a mobile calculator of these characteristics.

Abako's mobile was a metal tablet with parallel slots. The appropriate size buttons were moved through the slits. Each slit corresponded to a decimal order, except for the first two of the right. These were used for the dozen or upbringing of the AS and for the half, third and fourth of the dishes. Thus, the third right slot to units, the fourth to ten, etc. corresponding. In addition, each of the slots (except the first) was divided into two parts, with four buttons at the bottom and one button at the top. The buttons below were worth an order unit and those above five. This mobile calculator closely resembles the ball markers used in Far East and Near East countries.

From the destruction of the Roman Empire to the end of the Middle Ages, in Western Europe it was in the hands of a few sciences. These, once learned to read and write, addressed topics such as Astronomy, Geometry or Calculus. They did the calculation with their fingers and wrote the figure in Roman. It must be said that only specialists knew how to perform arithmetic operations and performed them through Roman Abbasics. At present, the specialist of the time needed many hours to perform the operation that a child could perform in a few minutes. When things were like this, those who wanted to become aware of the calculation were heading towards Italy, which then had a greater contact with Arabs and Byzanzios, and their classes were specialized in complex operations.

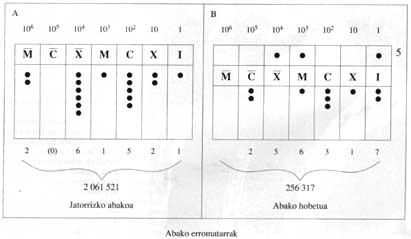

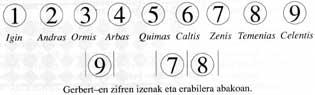

In 999 he was appointed Pope Gerbert d’Aurillac. He had previously studied Arab methods and tried to penetrate Europe, but found great resistance. In the beginning, the Arabic (Hindu) symbols introduced by Gerbert were written in branch bone tiles and replaced the chants in the abacus columns. However, retrograde calculators preferred printing Roman figures.

Between 1095 and 1270 stands out the Crusade. If their goal was to destroy the ideas of the infidels, they obtained other results. One of them was the awareness of the culture that some gentlemen and clerics present wanted to eliminate. As for the calculation, they knew the zero and the Hindu calculation techniques.

In addition, on the other side of the Mediterranean, in the Iberian Peninsula, specifically in Toledo, the contacts between both worlds intensified. Since the end of the 20th century. These two events resulted in the death of abacus.

Death accelerated in the 13th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, the mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci of Pisa, author of the book "Abaci Abaci". This treaty did not affect, as you could imagine, the arithmetic of the abacus, but the rules of calculating the figure on the sand. Therefore it became a manual to support the algorithm. Consequently, the science of numerical calculations (arithmetic) spread to the plain people. The simplicity of this calculation made the Church herself question whether the new arithmetic had something magical or insane. From there to burn in the fire some fiery supporters of Fibonacci there was only one step, taken by some inquisitors.

The truth is that the dispute between the abaquistas and the algorithmics spread for centuries and after winning new methods the abacus was used. XVIII. In the eighteenth century pen calculations were verified by abacus. While the new calculations were conquered by the scientist, traders, bankers, officials, etc. continued to use the abacus.

The French revolution ended up deciding the question. At that time the school use of abacus was prohibited.

The third type of abacus is that of ball markers. Markers are mainly used in Eastern Countries: In the Soviet Union, China, Japan, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, etc. In them we will see three different types: Types of stchoty in Chinese fire, bread, Japanese sorobe and Russian stchoty.

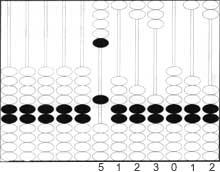

In the fire of China the origin of the corduroy is unknown, but we know that the XVI. In the twentieth century it was already used. In the fire (calculate) in the Chinese ideogram there is an abacus, an ideogram in which the hand represents below and above the bamboo. In the fire the corduroy is formed by four strips or stirrups that form a rectangle, several bamboo sticks (8-15) attached to the long stirrups, another layer that separates these sticks into two parts (top and bottom) and two on top and five on the bottom, and seven moving balls from top to bottom. Of course, the more canes we have, the greater the number that can be indicated.

In general, the two sticks on the right (columns) are left for those on the tenth and the hundredth, leaving the units on the third. The balls at the bottom are worth a unit of the corresponding order, while those at the top are worth five. The upper and lower balls to represent the numbers are taken to the intermediate layer.

Without his lips, the so-called Soroban of Japan was moved from China in the sixteenth century. In the 20th century, apika. XIX. It retained its original appearance until the mid-twentieth century. Then he lost a top ball and II. Since the World War they lost the fifth ball of the left bottom. In Japan there are still competitions of calculation by abacus or field. A calculation competition held in 1945 was very popular. Japanese field champion Kiyoshi Matsuzaki won four out of five tests on Thomas Nathan Woods, Japan's most experienced electronic calculators operator.

The Soviets knew the stchotya through the Arabs. Proof of this is its use in some regions of India and the Middle East. The Turks call choreb the coulbas and Armenians.

The stchoty of the Soviet Union is not the same as the previous ones. There are no intermediate stirrups. Each stick has ten balls, the two central ones (5 and 6) of different colors. In some stchotys, in some canes only four balls are placed for the fractions of ruble and copecas. In the stchoty, the number balls should go to the top strabe.

These three ball markers are currently used by many people in their villages, but above all by traders and traders.

Finally, note that in recent years the usefulness of teaching arithmetic to blind children has been recognized and that in schools good results are also being obtained in teaching mathematics.

So far we have talked about the history of the abaco, but to make it not history and to recover it from history, in the next issue we will give you the rules of use of the Chinese abaco. We recommend that you have a Chinese abacus if possible. Of course, at first you get stuck your fingers, you move the balls, you will be wrong in the calculations, but you will solve with experience and patience.