Paleoproteomics shows that Neanderthals made jewelry to decorate themselves

It has been half a century since some of the best-known artistic ornaments were discovered in the French cave of Grotte du Renne, until a study published in the journal PNAS shows that the Neanderthals have made them. For many years there has been a great debate and the new technique used has been paleoproteomics, key to knowing the origin of fossil bones.

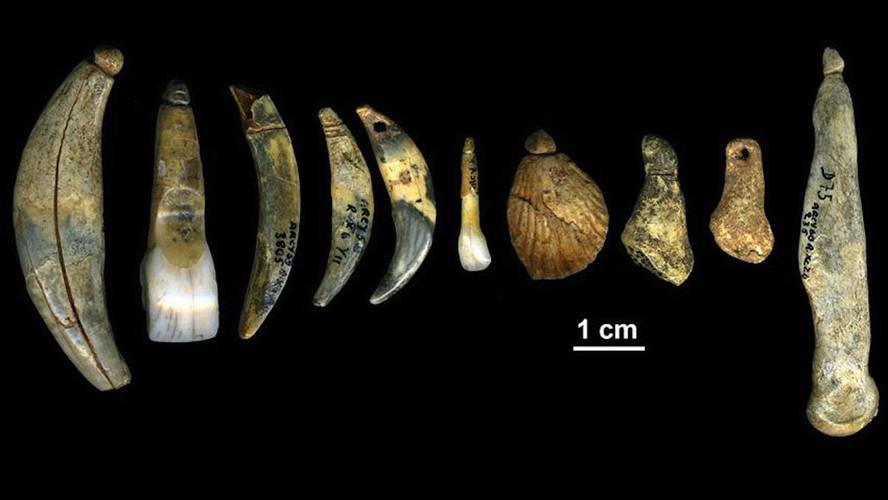

Grotte du Renne Cave contains important information to understand the transition between Neanderthals and modern men. It has remains of a lytic industry (Chatelperronian industry, some 40,000 years ago) from the time in which the two species lived in Europe: alongside the tools appeared artistic jewels made with animal teeth, bones and shells, together with which small human teeth could not be identified.

The researchers suggested that initially they were jewels made by Homo sapiens, believing that Neanderthals had no capacity for symbolic expression. Seeing that the traces of the broken teeth found could be the teeth of the Neanderthals, the researchers perhaps stated that mesh had been mixed in the excavation. But new research has shown that the samples were not mixed and the teeth are from Neanderthals. It seems, therefore, that the Neanderthals manufactured artistic jewels that adorned themselves, although still some researchers do not want to accept this cognitive ability.

However, the greatest contribution of the study has been the technique used, the paleoproteomics. Human teeth were very broken and could not know which human species belonged, but the extraction of proteins from these fossil teeth has allowed them to identify the origin of them. In fact, they have managed to extract collagen, a protein typical of the bones and have analyzed with mass spectroscopy the amino acid sequence of collagen. Like the Neanderthals, they have seen that it is rich in asparraginal matter and not in aspartic acid, as is usual in modern men.

The study reveals that although paleoproteomics is a new-born technique, the analysis of old proteins can open up many possibilities in the near future. It can help, above all, to differentiate the hominids from the late Pleistocene, since the samples of that time are scarce and, moreover, in many cases, the ancient DNA has not remained well.