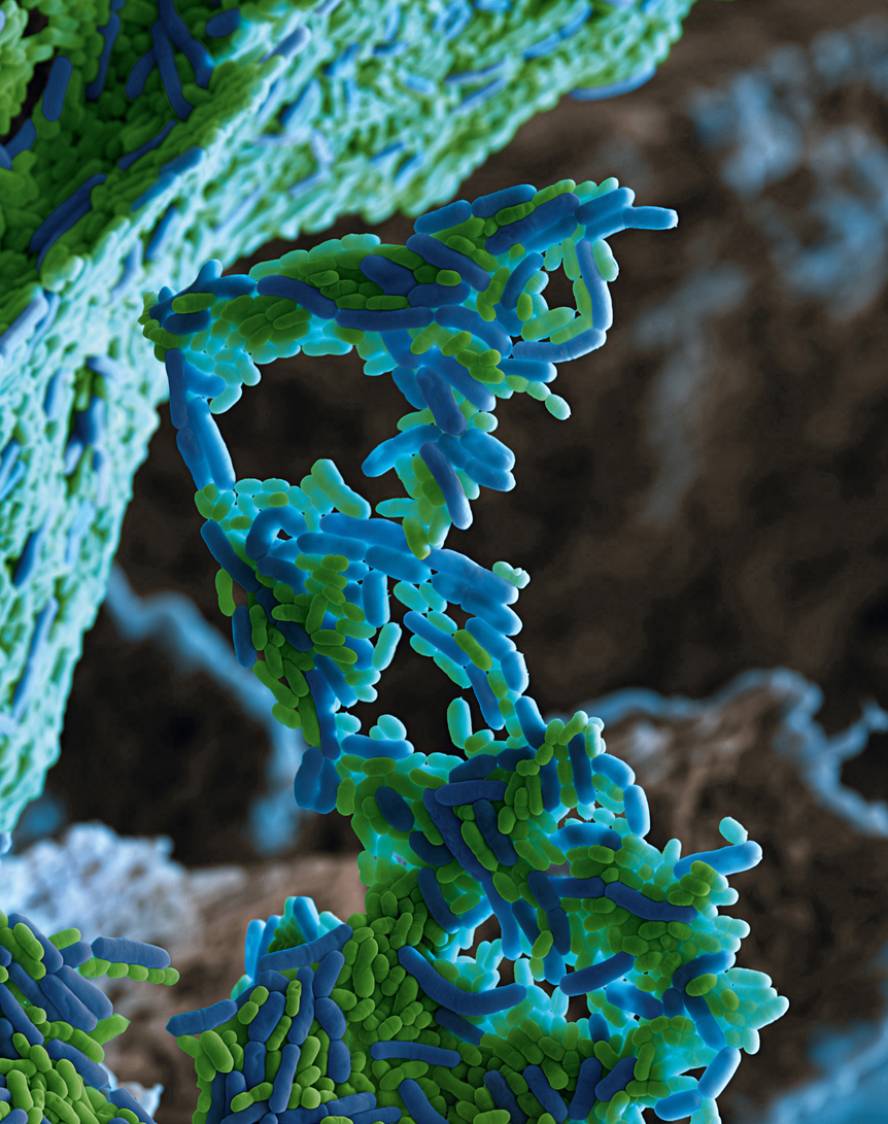

Knowing the human microorganisms

The sum of the genomes of the microorganisms that inhabit the human being has been called the “second human genome”. And we have 10 times more microorganisms in our body than cells and they affect us a lot. The consortium of the Human Microbiome Project published today in 14 articles the results of the 5-year work: 2 in the journal Nature (1,2) and 12 in the public scientific journal.

In 2007 the National Health Institute (NIH) of the United States launched the Human Microbiome Project (PMM). 242 healthy American adults took samples to men, 15 body points and 18 to women: 4 points of the skin, 9 points of the mouth and throat, nostrils, feces (as an indicator of the final microbiome of the intestine) and 3 points of the vagina. And in each person, three samplings were performed within 22 months.

After genetic analysis of these samples, according to researchers, they have identified most of the microbiome of these 242 people and have decoded the complete genomes of 800 bacteria. It has been proven that the diversity of microorganisms, both by body place and by people, is very different. Inside a person they have found the highest diversity in the feces and in the mouth and the smallest in the vagina. According to an approximate estimate, in the feces there would be about 4,000 species, in the teeth about 1,300, in the skin around the nostrils 900, and in the back of the vagina about 300. In addition, they have seen that one or several groups of bacteria predominate in each place.

On the other hand, although a person's saliva is one of the points with the highest diversity, it is one of the least changing from person to person, that is, similar communities are repeated, especially in people living in the same area. On the contrary, the communities of microorganisms between the forearm and the forearm (on the skin) are the ones that most change from person to person.

On the other hand, it has been proven that the communities of microorganisms of a healthy person are stable over time, which, according to the researchers, can be an interesting parameter of a person's health. In fact, the “Human Microbiome Project aims to lay the foundation for research on human health and diseases of the future,” says Broad Institute researcher Dirk Gevers, who has participated in the research, in a press release from this institute. “This is a huge resource, now public and available to the scientific community, to analyze how and why microorganisms change.”