Study of the archaeological ceramics of the Basque Country

However, previously, these ceramics are classified by archaeologists in various groups, depending on factors such as shape, function, decoration of ceramics and what they see by analyzing the pieces with the magnifying glass. To corroborate these groups and define the distinctive characteristics of each group, ceramics are subsequently made available to geologists.

Basic techniques

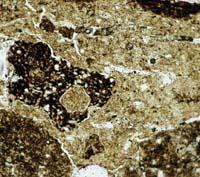

The geologists first carry out a petrographic study of the pieces received through a petrographic microscope. Compared to conventional, this microscope uses polarized light and the area where the sample is located is rotatable. They study in the microscope a fine sheet of ceramics and, based on the characteristics of the texture and the mineralogical composition of the clay and the reinforcements, perform a classification. In general it is more precise than the classification made by archaeologists.

After the petrographic study, they carry out a mineralogical study with the diffraction of X-rays. In most cases, from the mineralogical point of view, the diffraction of X-rays does not bring anything special to that observed in petrography. The exception is that these ceramics have suffered a very high temperature combustion. In fact, once overcome certain temperature limits, some minerals present in this clay can be destroyed and others transformed. These changes occur at certain temperatures. Thus, among other things,

The X-ray diffraction is used to check the presence or not of these mineral temperature indicators.

On the other hand, if the same combustion temperature is repeated in all ceramics, it means that the combustion technology was quite developed and controlled at that time. It is a very interesting fact from a technological point of view.

For example, according to the results obtained so far, it has been proven that the Romans burned ceramics more than 1,100 degrees if desired. In fact, they had very precise furnaces and also controlled very well the combustion conditions.

In addition to the Romans, Neolithic humans already knew what material they had to mix with clay to modify the physical-chemical properties of the original materials. For example, in one of the oldest ceramics in the Mendandia field (Saseta, Treviño), it has been observed that they added one or another complement to the clay according to the use of each ceramic.

The researchers interpret the treatment of clay and its purpose. For example, reinforcements are added to give consistency to ceramics; if you want to make kitchen ceramics, for example, carbonates are added to clay.

Finally, a chemical analysis of the pieces is performed to confirm the initial classification or to perform new groups. Likewise, this last technique allows to know the approximate origin of the clay that has been used for the realization of these pieces, that is, if the clay is near or more distant to the deposit, etc. For this purpose it is essential to know well the geological medium in which the deposit is located. The knowledge of the geological material of the source of this clay greatly facilitates the work.

However, it is not a matter of finding the exact origin of the clay, but of reducing it to a concrete medium. Two of the research groups have detected possible ceramics from Aquitaine and Bidasoa. Specific minerals have also been found, such as ophytes, which are very common in the ceramics of the Iron Age in the region of Pamplona.

In short, the UPV-EHU researchers collect a series of interesting facts about ancient ceramics that can hardly be seen through the magnifying glass.