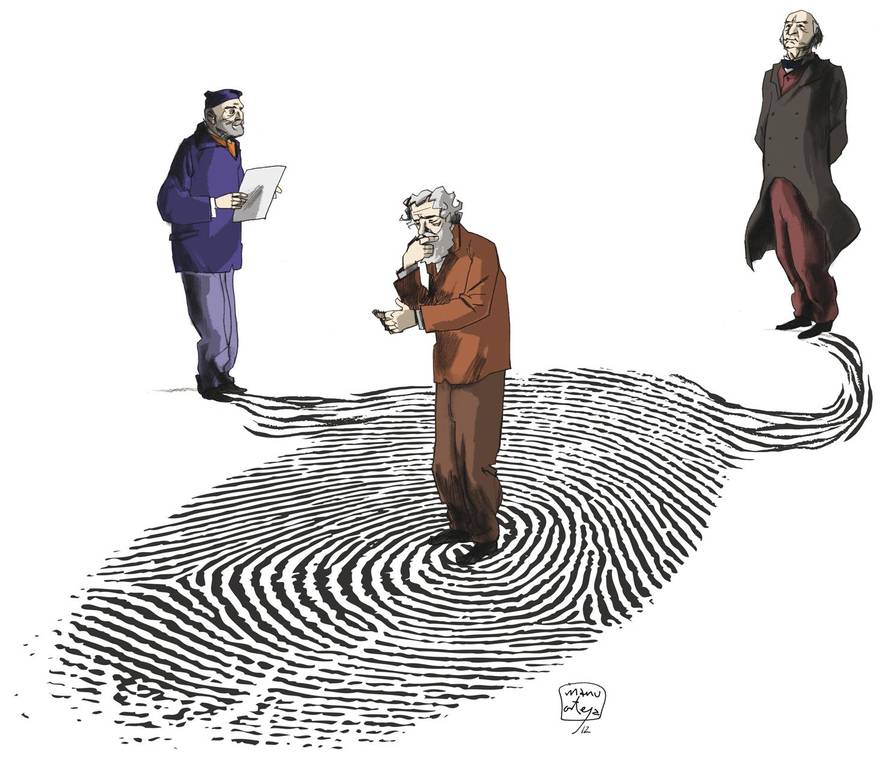

Fingerprints by William J. Herschel

Indian businessman Rajyadhar Konai was going to sign the contract, as usual, in the upper right corner, but Magistrate Herschel paralyzed him. With his experience on the insignificant value of the firm in those places, Herschel set out to carry out an experiment. He asked Konai to sign him by leaving the mark on his hand. He surprised accepted. Herschel took Konaire's hand and crushed it first on the ink he used for official stamps and then on the back of the contract. He liked the result and did the same with his hand on another page to compare both brands.

William J. The British Herschel, son and grandson of the prestigious astronomers John and William Herschel, was magistrate of the Hooghly region of Bengal (India). After five years of experience, in July 1858 he came up with a way to sign totally suspicious with the locals: "I wanted to scare me so I wouldn't deny the signature," he wrote. He was satisfied with the experiment and from then on all contracts began to sign it.

--> Brothers Herschel, from music to stars

--> John Herschel, Father's Witness

Soon, after trying with his fingers, he realized that it was more practical to catch only the fingerprints. In addition to asking for the signature of the documents, he also took it to his friends and to all that had occasion. The collection of fingerprints became a hobby.

Herschel realized that fingerprints could be appropriate for identification. In fact, those of each person were different, and it was quite easy to distinguish one from another. He also wanted to show if they were falsifiable. For this purpose he sent several fingerprints to the best artist of Calcutta to try to imitate them. It was impossible.

Therefore, fingerprints were a perfect signature. He began to use it with army pensioners to make sure they charged a single pension or to prevent him from continuing to charge after death. And then in their competition to identify prisoners in jail, where frauds were also common.

Proud of his discovery, in 1877 he wrote a letter to the inspector and the general registrar of prisoners to test the fingerprint system in the rest of prisons and administrations: "I send you a job that seems unusual but hopefully useful. In it is collected a method of identifying people, which I can say now, is much more reliable than photos for any purpose. (...) I can say that these brands do not change in 10 or 15 years. (...) I have received thousands of people in the last twenty years and now I am able to identify any of them if I have a “signature” of it. The response was unique and was not encouraging. He was frustrated.

Meanwhile, in Japan, Scottish surgeon Henry Faulds, director of the Tokyo hospital, was investigating the "skin lines". When visiting a site with an archaeologist friend, he discovered that in the ceramics of the site were observed the fingerprints of the artisan. He then began to experiment with his fingerprints and his companions and, like Herschel, he concluded that the design of the lines of the fingers was not repeated from one person to another, so they were suitable for identification. He also developed a method of classification of fingerprints.

With the intention of extending these ideas, he wrote to Charles Darwin in 1880. Darwin was already old and sick and passed the letter of Faulds to his cousin Francis Galton. He, committed to a thousand other projects, ignored him and transferred him to the Royal Anthropological Society. Faulds received no response.

That same year, Faulds published an article in the journal Nature: "On the skin-furrows of the hand". Among other things, he noted that in fingerprints he detected racial differences. He described how to take fingerprints with ink and proposed that it could be used to identify criminals, ethnological classification, etc. He also claimed that the design of fingerprints was absolutely sustainable, although he did not give a clear proof of this.

In addition, he told how he already applied it in two robberies. In the first case, by stealing the alcohol from the hospital laboratory, he discovered that thanks to the fingerprints left in the alcohol bottle, the thief was an employee. Second, in another hospital robbery, the thief used fingerprints left on the wall to demonstrate the innocence of one of those arrested by the police. But after a few years he would recognize that in this second case he did not really use fingerprints, but the shape of the hand.

Immediately after the publication of Nature's article, Herschel wrote a letter to the journal saying that she had been using fingerprints for her identification for more than 20 years. And I had doubts as to whether this method served with reliability to know the race of an individual.

In 1888, Galton had completely forgotten the letter sent by Faulds to Darwin when he also came to fingerprints on another path. Galton, a pioneer in anthropometry and one of the leading experts, asked him to study the method to identify the criminals of the French criminologist Bertillon. The method was based on the measurement of different parts of the body. Galton believed it was not adequate and came to fingerprints looking for a better alternative to this method.

He contacted Herschel, who offered him his collection. It was an immense material for Galton, which also increased the collection: It reached 8,000 fingerprints. I wanted to show that three requirements were met that I considered necessary to serve as a method of identification: that each person had different fingerprints, that were permanent (at least decades) and that they were easily classifiable, storage and comparable in large quantities. At seven years he confirmed the three. Thus, he scientifically demonstrated what was seen and suspected by Herschel and Faulds. He estimated that the likelihood of two people having the same fingerprint was one in 64 billion.

For Galton the work of Herschel was essential. Especially to demonstrate the durability of fingerprints. At the request of Galton, Herschel was able to resume the fingerprints of friends he had taken years before. And, as Galton himself wrote in 1888, "the best proof is that which Sir William Herschel has offered us with kindness. They are marks of the first two fingers of his hand, made in 1860 and 1888, that is, taken with a difference of 28 years."