Clara Immerwahr: chemistry, housewife, martiri

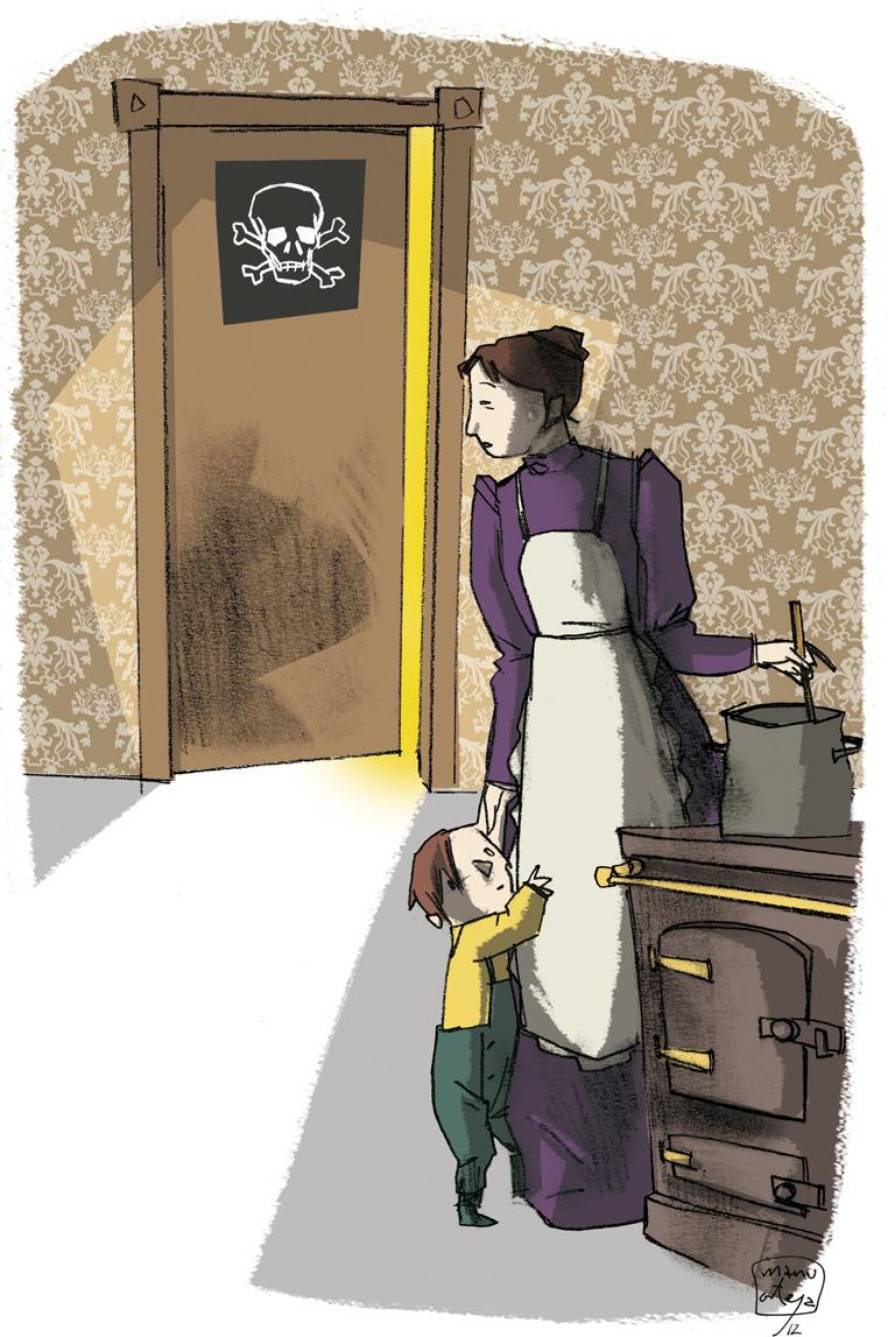

On May 2, 1915, at the small hours of the night, Clara Immerwarh, a doctor in chemistry drowned with the apron of the housewife, took the gun from her husband's army and left for the garden, tormented and desperate by her husband's activity. He had made the decision: his life ended.

Clara was always an intelligent woman. From a young age he proved to be an intelligent student. He accompanied his two older sisters to the female school. He particularly liked the natural sciences, and was angry when teachers spoke of the "obligations of women." Unlike her sisters, whose main objective was to marry, Clara wanted to follow her brother's path, who wanted to study university studies.

At the age of twenty he met the young Fritz Haber in a dance course. He fell in love, but refused to marry him because he dreamed of being economically independent. Thus, he began to study as a teacher and one of them, seeing the abilities of Clara, gave him to know the book Conversations on Chemistry by Jane Marcet. The chemistry was trapped since then. His father was also a chemist, and he liked his daughter to like chemistry. He would always be willing to collaborate with the studies.

After completing the teaching studies, Clara fought for the examination of access to the university. Finally, in 1895, teachers were allowed to go to the university. And Clara not only attended university studies but also a doctorate. She earned a doctorate in 1900, the first time a woman had a doctorate in Germany.

For a while she worked as a researcher and also taught "Physics and chemistry at home" in women's organizations and institutes. Until in August 1901 he married Fritz. At first, Clara thought she was going to be able to make married life and career together, but it was impossible for her. On the one hand, her husband did not help her much and, on the other, a complicated pregnancy, at first, and the fact of having to care for a child of poor health, forced her to stay at home.

However, at home she helped her husband, also a chemist, write a book about her research and the thermodynamics of gas reactions. This book, published in 1905, "dedicated it to his dear wife, Fritz--, Dr. Clara Haber, thanking her silent collaboration."

In addition, she continued teaching for women. And she realized, with rage, that many thought that her husband was preparing these classes.

Fritz, for his part, was taking great steps. Professor at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, together with Carl Bosch, he developed the process called Haber-Bosch. This process allowed to synthesize ammonia at high temperature and pressure, from nitrogen and hydrogen. The Haber-Bosch process was of great importance as it could be achieved for the first time thanks to a synthesizable product in a laboratory with different nitrogenous products (fertilizers, explosives, etc. ). The possibility of synthesizing fertilizers in all its forms offered great advantages on the one hand, and on the other, this process allowed Germany to produce explosives.

Meanwhile, at home, Clara was dissatisfied with her marriage. He wrote to his former thesis director in 1909: "What Fritz has won in these eight years, that -- and much more -- I have lost it, and everything that remains in me fills me with discontent... the main reason is Fritz's oppressive way of putting on first, which destroys anyone who is not as humiliating as he. The rest of the human values of the frits, except the will of work, are about to be exhausted and, as it were, is an old preterm."

In 1911 the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry was founded and Fritz was named after him. And they also gave him a professorship at the University of Berlin. They were great achievements and more taking into account the anti-Semitism of the time. In fact, Fritz, and also Clare, were Jews of origin, although both became Christians.

There was no shortage, however, people who complained that Fritz was not fully German. With the arrival of World War I, he had the opportunity to demonstrate his patriotism. In addition to organizing the Chemical War Section of the Ministry of War, he was responsible for the development of the weapons of mass destruction that are known and of various poisonous gases, including mustard gas. And he proposed the use of chlorine gas against enemies.

For his part, Clara hated that war, which was causing so many deaths and tragedies. And, above all, she could not stand the passionate dedication of her husband to the chemical war and use her scientific knowledge for that purpose. She condemned her husband as "perversion of the ideals of science." Desolate and frightened, he asked on several occasions to leave him. But her husband responded by accusing her of making statements of treason with the homeland.

The first gas attack took place on April 22, 1915, in Ypres (Belgium). Fritz was the one who led the attack. 5,000 soldiers were killed. Fritz was captain and returned to Berlin as a hero. The newspapers were full of praise to the new hero. At home, however, he did not have a great welcome. He had a strong discussion with his wife. He was the last.

Only his son heard the shot and he told his father. That same morning Fritz was heading east to lead the gas attacks against the Russians. He did so.