Evolution of therapies in 25 years

Samuel Broder is one of the researchers who laid the foundation stone in the fight against AIDS. During these twenty-five years he published in July in the journal Science Translational Medicine an article that explains the trajectory of anti-AIDS research. He has interspersed in the article his experiences and the convictions and feelings of society, with details about drugs. He was one of the specialists who treated some of the older patients affected by AIDS.

"Doctors know they now have several medications to administer to their patients, but many don't remember what the situation was at the time," said Broader. Nor was it clear whether there were pathogenic retroviruses for man.

However, "the fact that there was a retrovirus behind AIDS did not solve much: retrovirologists generally considered it more important to look for an antivirus vaccine than to develop antiretroviral therapies. Antiretroviral therapies were considered useless and patients, doctors and researchers were dissatisfied."

Although this conviction slowed research on antiretrovirals, some researchers decided to follow this path. Among others, Broader. Working at the National Cancer Institute in the United States, for the first time they were able to demonstrate that a particular drug partially inhibited HIV replication. They were the first results of a joint work by various private pharmaceutical companies and academic centers.

The results were released on 28 June 1985. It was not two years since this presentation until it was accepted as a treatment by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The pharmacy was named TR. In fact, it was a drug created in 1964 and confined in a laboratory. It was used in some cancer tests and subsequently ruled out for its toxicity. As for the treatment of AIDS, the benefits were greater than the damages.

This good result encouraged researchers to continue on the open path. Society also encouraged researchers and administrations to seek healing from this disease. "It was especially the groups of American gays who pressured, since they first detected the disease and many died," explains Daniel Zulaika, coordinator of the Osakidetza AIDS Plan. "This social pressure greatly accelerated the usual steps in clinical trials. The path that a drug travels for two or three years was the result --dio-- of antiretrovirals that were carried out for several weeks or months, which allowed the success of these therapies." Zulaika took up the work of coordinator of the AIDS Plan in 1987, and currently continues.

Repentisation

They took advantage of the rapid development of treatments and, as Broder wrote, "by 1990 we were quite clear that AIDS would cease to be a deadly disease and could be treatable."

But the real revolution came in 1996. Zulaika recalls: "At a Vancouver congress the results of an investigation were given: A group of dying patients weighing 33 kilos were resurrected upon receiving the treatment being investigated. As is normal, immediately, that same year and in 1997, patients began receiving this therapy in almost all health systems. At CAPV, for example, we had 2,200 patients taking this therapy by the end of 1997."

This sudden advance was due to two reasons: the development of a new type of medicine that combined with other drugs already developed. Thus, treatments became much more efficient.

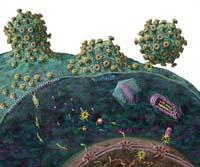

The key to combined therapy is to attack the virus at more than a moment in the infectious process. For infection to occur, viruses enter the cell first. Then begins the process of introducing your genes into the host cell genome. By having the information stored in an RNA chain, they make a copy of it and make it a double DNA chain. This copy is generated by the enzyme called reverse transcriptase of the virus.

The next step is to introduce the DNA chain copied into the host cell genome and, finally, when the cell generates protein chains from the information of these genes, they are cut to produce functional proteins. In fact, several proteins are synthesized from the united genes. These last two steps are performed by two other HIV enzymes, integrase and protease, respectively. From there, viruses only have to correctly join the components of the new viruses and remove them from the cell to complete the cycle.

Every medicine, a task

Each antiretroviral drug aims to interrupt a specific step in the infectious process and there are already six drug families. The first ones that developed, such as AZTI, affect the reverse transcriptase enzyme. In short, using the RNA chain as a model, this enzyme forms the DNA chain, adding nucleotides. Well, these drugs have a nucleotide-like structure and replace the real nucleotides in the DNA chain. Thus, they block the chain and break the synthesis of DNA. There are analogues of the four nucleotides that form DNA chains and more than one for each nucleotide.

Medications from another family also have the function of interrupting reverse transcriptase, but they act differently: they are associated with the enzyme and distort its three-dimensional structure. This makes the enzyme not working properly.

This revolution in the anti-AIDS treatment occurred when protein drugs were developed. By not being able to generate functional proteins, it is impossible to complete the cycle to viruses. In December 1995, the FDA approved the first anti-protein drug, Saquinavir. Since then other drugs have been developed with the same effect, as well as enhancers that allow these inhibitors to stay longer in the blood.

Recently (since 2006) medicines with other effects have begun to appear. Two drug families have the function of preventing the virus from entering the host cell and another of converting integrase into an unusable enzyme. Each of these families has a drug marketed and there are many studies underway to advance these pathways.

For Zulaika, "it has been very important not to have stopped researching and to remain cutting-edge and dynamic research." Twenty-four antiretroviral drugs already exist on the market and, as has already been said, combine different effects to attack the virus with greater hardness.

From research centers to users

Drugs marketed by research centers, pharmaceutical companies or others have proven effective at the time of launch. From there, professionals who have worked with these medicines transmit their experiences in scientific societies, congresses, etc. "defining the best combination of drugs in terms of cost and effectiveness," explains Zulaika.

From these experiences, clinical guidelines are published. In them it is recommended to combine this type of medication, avoid its administration once and for all, even aiming to take into account depending on the clinical status of patients, etc. Each country has its own guides. There is a European guide and scientific societies use their guides...

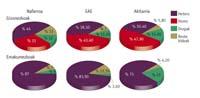

The European AIDS Clinical Association (EADS), for example, has on its website a guide for the treatment of adult patients infected with HIV. The guide offers different patient treatment options. In general, it recommends using two-nucleotide analogs along with another reverse transcriptase or enhanced protease inhibitor.

Since there is more than one drug per type, it offers different possible combinations and determines in which cases each of them should be used or avoided. The clinical situation of patients is taken into account, that is, if they are pregnant, have cardiovascular risk, have developed another disease, etc.

"However, it can be said that all guides are equivalent," explains Zulaikak--. If the guidelines are equivalent, I would say that all developed countries use more or less equal therapies." Nor has he noticed significant differences in the process of introducing medicines into health systems: "Sometimes the United States has been a little more advanced than the rest of the countries, but sometimes not."

The fight against AIDS has also developed in administrations. Proof of this development is "spending on antiretroviral treatments," says Zulaika: In 1997, 9 million euros were invested in the ACBC and 36.9 million in 2009. This amount accounts for 1% of the total expenditure of the health department. "It is terrible," says Zulaikak--. Note that the health department spends one-third of the overall ACBC budgets. All that money is invested in 4,600 patients."

Annual expenditure per patient has doubled practically in this period: It goes from 4,100 euros to 8,015 euros. "There are more and more patients and treatments are increasingly expensive. They are more expensive as they are more efficient."

This expenditure has improved the survival and quality of life of patients, to the extent that 25 years ago it could not be imagined. It should be noted that "at first it was thought that treatments would be of little use," says Zulaika. Thanks to them, AIDS is now a chronic disease. It is true that the virus has not been eliminated from the infected body. However, keeping the amount of virus controlled, the immune system of patients is not reduced, so there are no other diseases that ended up causing the death of patients.