The endangered Pyrenean glaciers

Snow and glaciers

Snow is the main component that mountain glaciers need, to accumulate year after year, form ice, deform by gravity, and start to move. In addition, in the glaciers of middle and tropical latitudes, the ice temperature is usually close to the melting point, so the discharge of water increases the lubrication and sliding of the ice mass. It's the glaciers.

However, depending on the situation and climatic characteristics of each mountain range or half polar, different types of glaciers can be distinguished, but all of them have two main characteristics: in the upper zone snow accumulates and the glacier gains mass, while in the lower zone the ice melts and losses to livestock occur at the top. This basic equation, called mass balance or glacier balance, is the main indicator of “health” of each glacier (Figure 1).

If weather conditions are adequate, part of the total snow a glacier earns in winter does not melt during the summer season, increasing the thickness and extent of the glacier. On the contrary, if climate conditions change, that is, if the climate warms, the melting of the top of the glacier extends to the entire surface and the glacier tries to adjust to the new situation. In this case, the glacier may have survival problems.

Pyrenean sentinels

Today, the largest group of southernmost glaciers in Europe are in the Pyrenees, which are on a climate border that accelerates their destruction. As if they were variable thermometers in the mountain range, these prominent highland geographical elements are very sensitive to environmental impacts. In addition, going back on the geological scale, in addition to carving the Pyrenees in the last thousands of years, they are responsible for the cultivated landscape that we can see today (along with many other processes, of course). It is therefore a symbol of the high Pyrenean mountain, since, in addition to providing the natural values mentioned, it also influences the ecosystems of the upper zone and generates a cultural value in the heritage and history of the mountain chain. We would say that for mountaineers it is also a sentimental symbol of the high mountain.

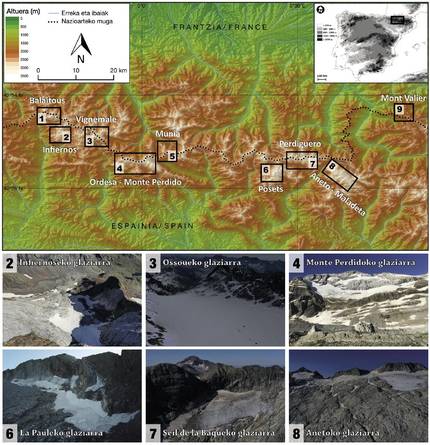

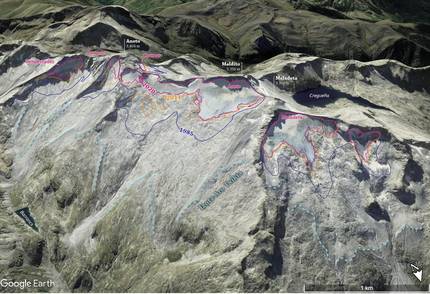

The current 21 glaciers are zocorated in the circuits of the highest massifs of the pyrenean chain (Figure 2). The most west is the Las Neous Glacier, increasingly reduced and located in the massif of Balaitous, while the most eastern is the small glacier d’Arcouzan, which remains on the northeast slope of Mont Valier Mountain (Ariege, France). The largest glacier, on the other hand, is still the 50-hectare Aneto glacier, but it has nothing to do with the glacial surface that the mountaineers of the last century were following to reach the top of the mountain range and its thickness.

Manifest regression

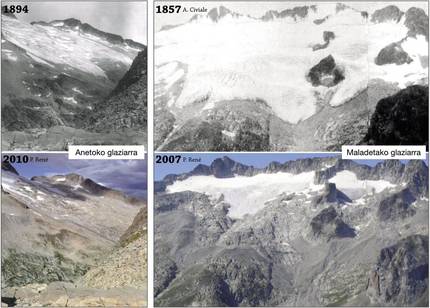

The decline and loss of dynamics of the Pyrenean glaciers coincides with the progressive transformation that has been studied in other mountain ranges that currently do not have glaciers, such as European summits and the Apenines. XVI. XIX. The Little Ice Age was a relatively colder global climate period between centuries, in which glaciers gained thickness and surface and also expanded in height down. Since 1850, 90% of this area has been lost per hour in the Pyrenees (Figure 3) and at least 33 glaciers have been extinguished or decreased to become an ice crab.

In recent decades, moreover, the decline of the Pyrenean glaciers has been remarkable, especially since the 1980s, since only 21 of the 39 glaciers currently remain. As is well known, the average temperature of the Earth has increased by 1°C since the pre-industrial era, a climate warming that has increased by human action, and is further amplified in most high mountain areas, so the Pyrenees are an example of this.

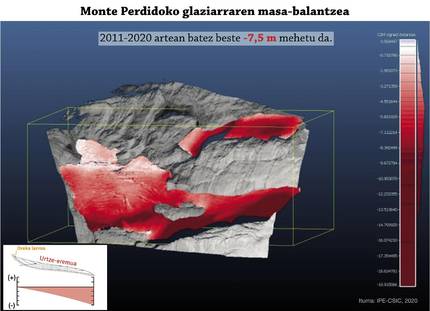

Thus, in collaboration with IPE-CSIC collaborators and researchers, in the field work carried out at the end of the summer of 2020 (beginning of the hydrological year), we used drones and a laser light system (ground laser scanner) to complete the relief models of the last remaining glaciers today. Of the twenty-one glaciers, we studied sixteen with drones and the Mount Lost Glacier with the help of the scanner, as the people of IPE-CSIC have done since 2011. Thanks to these novel techniques, for the first time we have managed to have a broad view at the level of the mountain range, which has allowed us to put exact numbers to the surface and thickness changes of the last Pyrenean glaciers in the period 2011-2020.

Field work and mountaineering

It's often that by saying that we're working in the field, people consider themselves a crazy scientist. If in spite of the bad weather it is not possible to fly with a helicopter, on several occasions we have had to climb the 30-kg scanner on the back to the balcony of Pineta, or when we study the thickness of the ice of the Aneto glacier, that which comes in shorts and slippers does not understand why we should carry a heavy dragon looking radar… However, over time we have seen that the field work is based on the experience. That is, we apply in our departures what today is “Alpine style” or light, and at the same time we enter a journey full of feelings. We're a rope of a few friends, we just take the essentials on the back and move from one glacier to another in the most efficient way possible, always guaranteeing the safety of us and the group.

Thus, in addition to the use of heavy scans, and to the extent that innovative technologies allow, we have started to use GPS and lighter devices (drones). Before, every massif or glacier was an exit of a few days; today, we can analyze more than one glacier on the same day and move from one massif to another.

The objective of the UPV-EHU sokada was also to study with a small drone the smaller and rocky glaciers, and to allow their flights we had to climb more than one mountain and a crest of 3,000 meters, with long and expensive days in Gabietous-Taillón, in Seil de la Baque-Portillón, in Posets... In addition, we accompanied the companions of the IPE-CSIC to the larger glaciers; to give the radio signal to the flights of the fixed-wing drone, we had to go up and down at other summits: Aneto-Maladetan, Posets and Infiernos, for example. One of the keys was to measure the new snow of the Monte Lost and Ossoue (Vignemale) glaciers so that the analyses carried out were as reliable as possible.

Surface loss and ice thickness

The latest measurements indicate that the surface area of the Pyrenean glaciers in 2011 was 297 hectares (ha), while in 2020 there are only 232 ha, i.e. 65 ha lost in nine years. The most visible decline has occurred in the larger glaciers, Ossouen (Vignemale), Aneto and Maladas, indicating that they are more sensitive to climate conditions. However, smaller and marginalized glaciers that significantly condition the topography have remained more stable, but have also suffered losses. Among the latter, the most serious are the glaciers of Barrancs, La Paul and Portillón, where signs of fragmentation and lack of dynamics are increasingly evident.

As for ice thickness, between 2011 and 2020, the Pyrenean glaciers have thinned an average of 7.3 meters. And the glaciers have had different responses (Figure 4). The biggest changes are much larger than the average (between 10-12 meters), such as the Seil de la Baque and Aneto glaciers. We know that the Aneto glacier, the largest glacier in the Pyrenees, is about to split into two and that the division will only do more harm in the future fusion process. The smaller ones and the more zócalos, on the other hand, are less thinned (between 3 and 5 meters). In total, if we put in aquatic values the ice loss of the Pyrenean glaciers in the last nine years, we could say that in the last decade, 20 million tons of water has been lost.

Pyrenees in imbalance

Most mountain glaciers in the world are suffering the effects of climate change, and the Pyrenees are no exception. Studies have shown that the accumulation areas of the Pyrenean glaciers are becoming smaller and, in most cases, there is no accumulation. In other words, in the summer season, in addition to melting all the snow they earn in the winter season, they lose the ice that existed and, therefore, they thin the glaciers and lose surface (Figure 4). It's a significant symptom that Pyrenean glaciers will not be able to survive under current weather conditions. Therefore, if current rates of decline and thinning persist (and so it seems), the glaciers in the mountain range are about to be completely lost in the next 20 years.

Consequently, a unique geographical and geological element of the Pyrenees is about to disappear in the coming decades and we can already see and understand it with our eyes. The farewell of permanent and mobile ice masses, characteristic of the high mountains on Earth, is taking place right now, but the disappearance of these glaciers will not be an environmental catastrophe, as they contain little water. However, our descendants will not be able to know this landscape so close to home. Pyrenean glaciers are also the preachers of what is happening in other parts of the world; the vulnerability of mountain glaciers to climate change is evident and, as is currently the case in the Pyrenees, glaciers in other mountain ranges may be in danger of extinction in the future.