I want to go to heaven

The eighteenth century was surprising from a scientific point of view. Some designed underwater breathing, gas research gadgets and ways to fly. All this, long before the Industrial Revolution. And not only before the Industrial Revolution; the parachute was invented before the French Revolution in 1785. And that means there were already reasons to use it. Someone asked for safety.

The truth is that someone in his search should not go much further back, but to find the first experiments in the near sky. To do this we must go to the time before the independence of the United States and to the time before the birth of Mozart.

Pulling the thread

The date of the first significant experiments was 1749. A man tried to measure the air temperature over him. But he could not fly, so he had to invent something else. How can you experience them in the sky without lifting your legs off the ground? Up to the mountains, of course. But with much effort they did not reach very high heights. And besides, the land was there, near the place of the experiment.

They would have to do something more to investigate 'heaven'. Surely use some tool. The simplest thing is a kite. Scottish Alexander Wilson tied the comet with a thermometer and tried to measure the temperature of the sky. That is why Wilson has a place in the history of science. It did not get great results. The thermometer could not go up much. But the idea was original; three years later another also launched a comet with the intention of conducting an experiment and got a great fame.

Although he hadn't done that experiment, he would actually be a man of great prestige, Benjamin Franklin. The experiment is known. The comet, carrying a metal needle, was silk and Franklin tied a key to the bottom of the thread. He was brave, took off with a storm and the electricity from a cloud reached the key. The ultimate goal was not to investigate the sky, but the electricity itself, but it showed that clouds are charged with electricity during storms.

Inflate and raise

Experiments conducted by Alexander Wilson and Benjamin Franklin were the first scientific attempts to study the atmosphere. First approach to heaven. But they did not stray from the earth. They were not true explorers. The era of atmospheric explorers began thirty years later, in 1782, by the daring French brothers Joseph-Michel and Jaques-Etienne Montgolfier. The two brothers launched the first ball by heating the interior air.

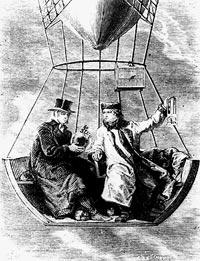

Improvements after the balloon flight confirmation. On the one hand, hot air was replaced by hydrogen. On the other hand, if the ball went up, it would also allow passengers. To do this, the Montgolfier brothers added a large basket to the ball and introduced some animals on the first manned flight. The first travellers were a sheep, a duck and a rooster, on September 19, 1783. Shortly after, the man dared to fly on the ball.

The first record of flights made by man dates from November 21 of that same year. Two nobles from the court of King Louis XVI took off on the rooftops of Paris and made a flight of twenty-two minutes. They took the land in a vineyard and were the farmers in the area to see what the 'fallen dragon from heaven' was. The peasants were willing to defend themselves, but the nobles offered them champagne. In France there is still the first flight of man.

Joseph-Michel Montgolfier also blew to the ball. At least once. According to the documentation, it was on January 19, 1784, in Lyon, the greatest ball of all time. Since then, the history of balloon flights is full of ephemeris.

From a scientific point of view, the most important is that of flights made by the American John Jeffries. Parachute inventor Jean-Pierre Blanchard and barometer Jeffries left the ball. In one of them, they also traveled from coast to coast of the English channel. Some measurements were made, but the importance of these flights was a precedent. In a few years, the exploration of the atmosphere would have taken a big step.

Thousands of meters

The breakthrough was an exciting exploration trip, an upward flight in France. Man climbed above the highest mountain in Europe. But the journey was not made by a standard explorer, a conventional adventurer, but by a chemist, Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac. The reason for the flight was not the same adventure, but the desire to conduct a scientific experiment.

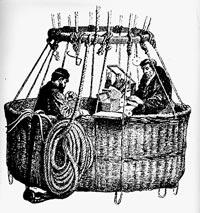

The money from the experiment was provided by the National Institute of France. Therefore, the main objective of this flight was science. How did gas work at the top of the atmosphere? And above all, how was the magnetic field there? According to a theory published in 1803, the area affected by the compass weakened rapidly as the atmosphere ascended. In search of answers, two people made the first flight, Gay-Lussac and the brave physicist Jean Baptiste Biot. Two friends who could include all the portable scientific tools.

They left on August 24, 1804, at ten in the morning. Gay-Lussac himself explained the circumstances of the flight: "the climb was slow, very carefully. When we plunged into the clouds, about two thousand meters, we measured the oscillations of the magnetic needle, but it was useless because the ball was spinning." Static electricity was more pronounced as it rose. Finally they were delayed and had to go down. Gay-Lussac's goal was to climb to about six thousand meters, but they did not.

The chemist did not stop. On September 16 he flew only the second and beat all records. He climbed faster than in the previous flight and, among other things, was able to measure the temperature change: he went down a degree when he climbed 173.3 meters.

It reached six thousand meters and Gay-Lussac wanted to climb more. To do this, he had to lighten the ball and threw down a wooden chair. The chair fell close to a group of pastors and a scandal arose. They didn't see the ball, it seemed that the chair had fallen from the sky.

Gay-Lussac took air samples at 6,636 meters. And he continued to ascend. In the end, when he reached 6,977 meters, he decided it was time to go down. The truth is that I had to go down, I had to collect the samples that had to be collected and there the higher conditions were not suitable to stay long. Gay-Lussac was frozen, had the pulse and heart rate very fast and the air was very humid. Descend and take the land near the city of Rouen, taking off in Paris, traveling about a hundred kilometers northwest.

Life in danger

The journey was surprising; early 19th century technology could not be more profitable. But there was no danger in stopping research; in that century, both technology and science, as well as exploratory instinct evolved rapidly, and the mixture of these three provoked madness in atmospheric exploration.

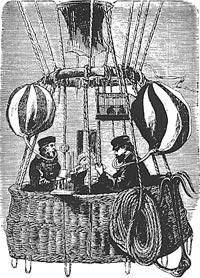

In 1862, a UK scientific organization put money to make several flights into the high atmosphere. A member of the Greenwich observatory showed up to fly on this ball, the British James Glaisher. He was with Henry Coxwell, a ball pilot and a friend of Glaisher. The project had the appearance of scientific research, but eventually became a record high race.

They made two flights. On 17 July both amounted to 7,979 meters and on 5 September it was not clear how far. According to them, they reached a height of 36,000 or 37,000 feet, but it is not credible; 36,000 feet are 10,973 meters and at that height would only survive a few seconds. Glaisher lost consciousness, but thanks to Coxwell's work they returned alive. According to estimates and their stories reached a height of 30,000 feet, about 9,100 meters. Far above, in any case.

In 1875 the French Théodore Sivel, Joseph Crocé-Spinelli and Gaston Tissandier faced a similar challenge. On April 15, a balloon flight called Zenith broke Glaisher's record. The three knew that in those high flights the lack of oxygen was a serious problem. They spoke with the main expert of the time and installed an air conduction system with oxygen in the ball.

However, the flight was tragic. He climbed much, more than 9,000 meters and suffered the consequences of the air. All three lost consciousness before or after and only Tissandier survived.

According to him, stunned, he woke up from time to time and tried to control the ball. The ball dropped very quickly, although the Tissandier cuitado tried to slow down. The landing was very hard, but at least I was alive. The other two dead. But he did not kill the blows, but the hypoxia, the lack of oxygen.

It is difficult to value the courage of those men. What were they, heroes or fools? For some, both things at once. They climbed to about nine thousand meters! Height that occupies almost a commercial plane! It is not clear whether that madness was worth it or not. It must be said in his favor that he did make contributions to science. They helped clarify how temperature, pressure, and the amount of oxygen changes with height. They also collaborated in the research of the behavior of gases from the chemical point of view and the functioning of the respiratory apparatus from the medical point of view. They often acted as rockets for doctors. But perhaps it was too much, the scientific contribution was too limited, seeing how many risked.

Aerostatic Probes

It was clear that it was better to send unmanned probes to investigate the upper part of the atmosphere. This type of research began in the late nineteenth century. In 1892 the first probes filled with scientific instruments began to be sent. They easily surpassed the height of Glaisher and Tissandier, providing reliable data to the ground. For example, at eleven kilometers high the temperature is about 55 degrees below zero.

And not only that. Soon after they realized that above that height the temperature does not drop but rises. These 55 degrees below zero are minimal. Increases or decreases the temperature in the atmosphere. With this data we began to understand that in the atmosphere there are several layers and that they are different from each other. The man began to look at the strategist.

The aerostatic probes are ideal for the study of these upper layers. Planes have also collaborated in atmospheric research. And other devices like satellites. But aerostatic probes (balloons) are still essential to bring science from the sky.

The topic of explorers is different. Modern 'crazy' explorers continue to commit. But these follies have no scientific excuse. Some are produced by breaking records. For example, the biggest jump in the parachute has occurred from a height of 40 kilometers. Glaisher and

Four times above Tissandier brands. It is difficult to consider such heroes as explorers. However, it is easy to go crazy.