Garoña: countdown begins

From the beginning of the year, the Garoña nuclear power plant is standing. In principle it was authorized to act until July of this year, with the possibility of extending until 2019, since neither the Nuclear Security Council (CSN) nor the Spanish Government saw impediments to continue operating the plants. However, Nuclenor, owner of the plant, decided in late 2012 to remove the fuel from the reactor and cut off the activity. A month later, the government announced the definitive closure, although some media outlets point out that it is possible to reverse.

Nuclenor, formed by Endesa and Iberdrola, noted in his note of 28 December 2012 that the closure is due to the new government tax on nuclear power plants. Specifically, the Spanish congress decided at the end of December to establish a new tax on nuclear fuel used and radioactive waste generated. The tax is retroactive, so Nuclenor would be obliged to pay 153 million euros.

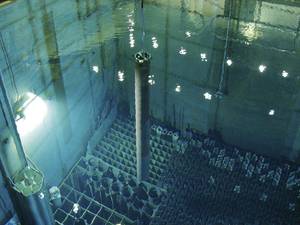

According to Nuclenor, this payment would be a disaster for employers and workers, so he decided to leave the reacting uranium bar and keep it in the inactivation pond "to protect workers' rights and the economic capacity of demolition jobs." Otherwise, from the first day of January, you would be required to

pay the tax.

Although environmental groups have eagerly taken the closing announcement, the reasons are economic and not others. For example, engineer Marcel Coderch believes this. "It should not be forgotten that from a technical point of view it had no impediment to operate until 2019, although the plant would already be 49 years old. And economically, if it continues to operate under the same conditions as it has so far, it would only have benefits, as it has long ago amortized construction costs."

That's why Nuclenor wanted to extend Garoña's performance. "Until the government decided to get some of the money it needs from nuclear power plants. Thus, he announced that at the end of the year he was going to apply new taxes and, therefore, Nuclenor does not get the bills right," explained Coderch.

Specifically, it would have to pay 2.190 euros per kilogram of fuel used. Coderch, however, does not seem disproportionate. "In Germany they pay 145 euros per gram of fuel, that is, 145,000 euros per kilo, 66 times more than in Spain."

In addition, if you wish to continue working, Nuclenor should undertake work to improve security measures by order of the European Union. In fact, after the Fukushima disaster, the European Union, concerned about the security of existing plants in the territory, carried out specific studies that showed the need to improve the security measures of many plants, including those of Garoña.

The action plan presented by the CSN in December last year in the European Union indicates that it should reform the structure to combat natural disasters, increase the reliability of the insulation capacitor, ensure permeability to avoid accidental drains... All this would force Nuclenor to make big investments.

Garoña is the second central in Spain. The first was the central José Cabrera (Zorita), which went into operation in 1968 and ran for 38 years until the government issued the closing order. La de Garoña began in 1971 and was the largest in Western Europe in its time. Currently it is the least capacity of the reactors in operation in Spain: It has a capacity of 466 MW, approximately 6% of the total productive capacity of Spanish nuclear power plants.

Limited experience

Now it seems that it will definitely close. The first step will be the design of the demolition plan, according to the criteria of the International Atomic Energy Agency (CECA). Subsequently, once the plan has been submitted, approved and authorized, the work begins. These works are carried out under the responsibility of Enresa, company in charge of radioactive waste in Spain, and are long-term.

Coderch recalled, however, that they have already done their first job, that is, they have removed the fuel from the reactor and have saved it in the pond. "It will also be the first time such a power plant will be demolished in Spain." It has a boiling water reactor (BWR), one of the few Europeans, and the twin of the total decomposition of Fukushima.

At the moment there are two plants in demolition phase: Vandellos I and José Cabrera. The reactor of the gas-cooled Vandellos I plant (GCR) is only 39 in the world. The demolition began in 1998 and since 2003 is in the second phase of the demolition, that is, only the reactor remains for its complete demolition. Once this is done, it will enter the third phase and the owners, Enresa and Iberdrola will have to decide what to do with the space that has occupied the central.

Meanwhile, they are at rest: The Vandellos I reactor is framed in a gigantic structure in which no one can enter until about twenty years pass. Until then, technicians carry out the usual monitoring and review tasks to ensure the absence of incidents.

The demolition of the central Vandellos I has been a pioneering experience for Enresa, after which the works of the central Zorita have come. With pressurized water reactor (PWR), it operated until 2006. That year the government ordered the closure of the plant and 4 years later authorized the start of the demolition plan in 2010. They are therefore in the first phase of demolition.

Therefore, Spain does not have much experience in the demolition of nuclear power plants, but it is not surprising: They are given a lifespan of between 40 and 60 years (in the United States there are 71 reactors authorized to act for 60 years), age to which they have already arrived. The oldest reactor in the world is 44 years old and so far very few power plants have been knocked down, namely eight in the United States and one in Japan. Closed or suspended, 143 reactors, most in Germany (27), the United States (28) and Great Britain (29).

What is coming, future

Garoña will soon be added to this list. Nuclenor did not want to talk to Elhuyar magazine, so some questions remain unanswered. However, there are questions about which there is no doubt.

For example, Nuclenor has stated on numerous occasions that the electricity generated by the Garoña plant was essential to meet the energy needs of Spain. Marcel Coderch denies it: "The Garoña plant has been a symbol for the nuclear industry, but it is very small [it has capacity to generate 466 MW] and the electricity coming out of it is not at all necessary."

Francisco Castejón is a researcher at CIEMAT (Center for Energy, Environmental and Technological Research) and responsible for Ecologists in Action on nuclear energy issues. Coderch matches: "The Garoña plant is totally despicable." According to him, the plant is very obsolete and has clear deficiencies in security measures, "but if it is not necessary, so it does not make sense to continue working".

Further, Coderch said: "The data show that Spain currently has an electric surplus. Spain has enough wind farms and combined cycle power plants to meet energy demand." However, according to the 2012 Ministry of Industry report, taking into account the power plants generating more than 1,000 MW, 21.77% of the total electricity produced comes from nuclear power plants.

However, looking ahead, it seems that nuclear energy will lose strength, not only in Spain, but also around the world. This is evidenced by, for example, the European Union's energy forecasts for 2050 and the change in the construction of new power plants.

In fact, in recent years, more and more experts have warned that the trend should not be how to achieve an increase in energy production to respond to growing needs, but to reduce consumption, an aspect in which the European Union has joined.

On the other hand, a few years ago the nuclear industry suffered a certain recovery considering that the energy was clean; its supporters assured that it helped reduce carbon dioxide emissions and it seemed that they were going to build new plants there and here. Now, however, most of the intentions have remained in nothing.

Coderch is clear: "In these times no one wants to build a nuclear power plant in Europe. Expenses have skyrocketed and it is very difficult to monetize this investment. That is why they want to extend to the maximum the life of the plants in operation. Given this, I think it is necessary to reach an agreement between the owners of the plants, governments and society. Everyone would have to decide how long a plant can maintain its activity, as over the years the owners will increase their income, but at the same time increases the risk of an unforeseen occurrence."

According to Coderch, Spain has an important vacuum in this regard, but in other countries the problem is even more serious, especially in France. There his dependence on nuclear energy is very large: They have 58 reactors and produce three quarters of the energy they consume. "This dependency is unreasonable, at a time when a big mistake was made, and now they will have to decide how and with what to replace nuclear power plants as they reach the end of their useful life."

Returning from France to Garoña, Coderch wanted to clarify that the cost of the demolition of the plant is "theoretically" covered, since Enresa charged an amount of money per kilowatt generated by the plant to cover the demolition. "The truth is that you can't know how much is going to be really spent, not so much on demolition work, but above all on the safe storage of radioactive material."

Question pending. Francisco Castejón has spoken clearly: "For hundreds of thousands of years we have generated waste that will be radioactive without knowing what we will do with them. The only thing we can do until we find a solution is to create no more."