Cannibal Neanderthals of Northern Europe, close up

So far, most of the tracks to meet the Neanderthals have been produced by deposits from southwest Europe. Thanks to these clues, for example, it has been discovered that their behaviour towards the dead was not the same in all places and times. For example, in Chapelle-aux-Saints (France) and the Sima de las Palomas (Spain), the dead were buried, while in Les Pradelles (France) and El Sidrón (Spain) the dead were fragmented and their bones were crushed to feed. Elsewhere there have also been clear remains of cannibalism, but all of them in southwestern Europe.

With fewer deposits in northern Europe, researchers did not know if there were such differences among Neanderthals in the country. At the sites of Feldhofer (Germany) and Spy (Belgium), evidence has been found that the dead were buried. Apart from that, they didn't know much more. Now, a group of international researchers have shown that the Neanderthals who lived in a Belgian field were cannibals.

The team led by University of California researcher Hélène Rougier analyzed the fossils of the Third Goyet Cave. It is the richest site of northern European Neanderthals, where 99 fossils have been identified and where the first traces of cannibalism of northern Neanderthals have been found. The results and conclusions of the study have been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Forming the puzzle

Paleoanthropologist Asier Gómez Olivencia is one of the signatories of the article. She has confessed that she has only done a small part of the work, but is very happy to have been able to participate. He has described the research as important, since it has been of great help “to obtain new data from fossils from ancient excavations and to complete the photo of the Neanderthals”.

He explains that in some times the northern territories were depopulated due to the cold. “Therefore, unlike the south, the population has been interrupted and the deposits and fossils are much more scarce.” Therefore, the site of the Third Cave of Goyet has a special relevance, not only for the number of fossils but also for the information obtained.

The site was excavated long ago and more than once and in total more than 30,000 fossils were found. Rougier's group has studied them one by one, identifying 99 fossil Neanderthals, 96 bone fragments and 3 teeth. Gómez himself has discovered some of these parts and has also analyzed ribs and vertebrae, because he is an expert in these parts.

Specialists from different areas have also collaborated, who as pieces of a puzzle have joined each other forming 47 large parts of 35 bodies. They have concluded that there were at least five Neanderthals: four adults and one child. On the other hand, with the carbon test 14 bones have discovered that they are between 40.500-45.500 years old. Thus, they were the last Neanderthals of northern Europe.

In addition, they have analyzed the mitochondrial DNA of the samples and compared it to the 54 most modern men, 8 presecuenced Neanderthals and one denisovés. They conclude that the Neanderthals of Goyet were similar to other distant Neanderthals (Germany, Spain, Croatia), more homogeneous than the modern men who today live at these distances. The results corroborate what was proposed by previous paleogenetic studies, that is, that the Neanderthal population in general, and especially that of the last Neanderthals, was reduced.

Traces of cannibalism

Although genetically homogeneous, they had great cultural diversity. “In that we are similar,” said Gómez. Even more: “That’s why I find it easy to identify with them.” Proof of this diversity is their behavior with the dead, and the remains found in the Hiru cave of Goyet confirm that in the north there was as much diversity as in the southwest.

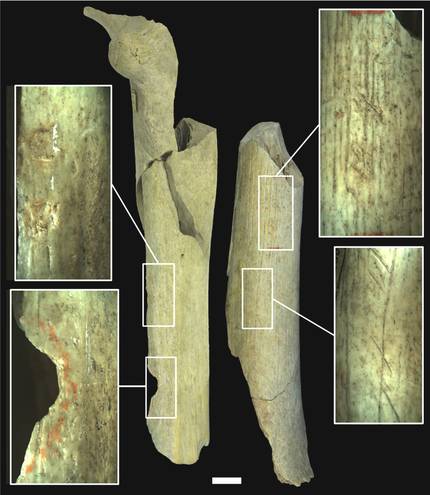

The traces of cannibalism are clear. A third of the Neanderthal bones were cut and many had traces of the blows they had given to draw the marrow. At the site there were also bones of other species hunted and eaten by the Neanderthals, especially reindeer and horses, and they have seen that the bodies and bones of their limbs were cut and destroyed like those of those animals: they separated the parts of the body, removed the cavities, breaking the long bones and whitening the ribs and skulls.

However, researchers cannot say whether cannibalism was performed within a rite or simply to feed. According to Gómez, to resolve this doubt they would need information provided by the context, “and in this case that has been lost, we only have bones. Elsewhere it has been seen, for example, in ritual cannibalism, that human bones are in a separate place, not mixed with animals. On the contrary, in the case of the Homo antecessor of Atapuerca all are mixed, its cannibalism was not going to be ritual but gastronomic. We have no information about the type of Goyet.”

Bones, tool

Bones, in addition to feeding, contain traces that demonstrate their use as a working tool. It has also been a remarkable discovery. Only in four places have been found the human bones with which it has been worked and, in addition, Goyet is the only place with more than one grain.

These traces have been found in three warm and in a femur. Apparently, they were first crushed to eat and then, seeing that they were fit to work the stone, they were used as those of other animals.

Specifically, the researchers have concluded that they were used to retouch and refine stone tools. In his opinion, they would surely have realized that the bones that were being used were human, but, as with cannibalism, in this case they do not know whether that use was part of a symbolic behavior or were used as appropriate for this function as animals.

Excellent example of collaboration

The study of Goyet's bones is a good example of collaboration, according to Gómez. And without the participation of experts from many specialties the result would not be so good.

The seed of research was brewed long ago. In 2004, Dr. Hélène Rougier and Isabelle Crevecoeur identified a Neanderthal tooth and jaw fragment in a collection that was stored at the Royal Institute of Natural Sciences in Belgium. This discovery was the starting point for a detailed study of the entire Goyet collection (over 30,000 bones). Subsequently, an interdisciplinary team was formed to investigate human bones that identified 283 human fossils, including Neanderthals.

“My specialty is the ribs and vertebrae of hominids. During this research I was in another project with Isabelle. However, I had the opportunity to see the ribs and give some information. Although by then they had studied the collection twice, I asked them if I could look for the third time. They gave me the approval and in this third phase we managed to find more bones. Then I participated in the description of ribs and vertebrae,” explained Gómez.

In his opinion, participation in an international group of these characteristics is very enriching, since collaboration offers a unique opportunity to learn: “It is very interesting because you know the different ways of doing the work and researchers from different specialties gather. I really enjoy this exchange of knowledge. And also, with human bones, it always generates a special emotion to find and identify a human bone.”

He also highlighted the difficult identification work done by Rougier and Crevecoeur: “Identifying a small human fragment among thousands of animal bones is not easy.” He also highlighted Rougier’s management to carry out the article: “He has taken into account the suggestions of all the authors. We were also a great team of work, difficult to coordinate, but Hélène has done it perfectly.” The entire study has therefore been based on collaboration, from the observation of the bone stack of the cave to the publication of the article in the scientific journal.