Basurt: birth of a hospital

For Bilbao, the second phase of the century was even more complicated. In the first half of the century, Bilbao was a very well organized and little populated city, about 10,000 thousand. The water was collected from different sources in the city and had infrastructure to expand drinking water and advanced public health measures. Mortality rates were lower than in the second half. What happened? It is not difficult to succeed: The expansion of the Biscayan steel industry meant population growth prior to the organization of the social structure. Public health took a big step back and infectious diseases increased mortality rates. On the left bank, in the heart of the steel industry, life expectancy declined in ten years, doubling infant mortality.

On the other hand, cholera appeared in Europe and Spain and the first epidemic entered Bizkaia in 1834. Cholera and tuberculosis were undoubtedly the 19th century. diseases in which the century was wounded. And with them, tuberculosis, flu, cholera, navarrería, measles, typhoid fever, syphilis... With these considerations the Civil Hospital of Bilbao was built on the grounds of Basurto.

The current territory of the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country then had 600,000 thousand inhabitants, of which Bilbao agglutinated 80,000. Each woman had 3.53 children and a half-life expectancy of 35 years. Although infant mortality data are scarce, they were high: 200 of every 1,000 born in the first year died.

As for healthcare, it must be said that Bilbao had a hospital, that of Atxuri. It opened at the beginning of the century, with 250 beds and was quite empty, at least in the first half of the century.

New hospital and XX. century

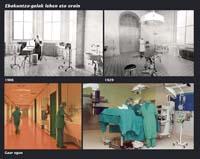

Until then, hospitals, such as Atxuri, were those built in block, but from the second half of the century, driven by hygienists, the most advanced countries in the world, Northern Europe and the US, began to apply new architectural approaches. The criteria on which these new designs were based had much to do with the control of infections, with the limitation of their diffusion. Hospital blocks gave the relay to hospitals formed by pavilions.

The organization in more than one pavilion involved not confusing infectious diseases with others, and could lead to the isolation of certain patients. From that time they were Lariboisière of Paris (1854), Tenon (1875) and Hôtel-Dieu (1876), Blackburn of England (1859), Edinburgh (1878) and J. of Baltimore of the United States. Hopkins Hospital. The system of pavilions had its greatest diffusion in Germany, being very famous, among others, Friedrichhain of Berlin (1868) and Tempelhof (1878) and Eppendorf of Hamburg (1892).

The organizing entity for the construction of the hospital, Junta de Caridad, made a request to two Bilbao citizens, Dr. Carrasco and Architect Epalza: They had to travel through Europe, visit hospitals and bring new ideas from them. Thus, doctors and architects made a three-month trip through many European countries. The architect takes as a model the Eppendorf Hospital in Hamburg.

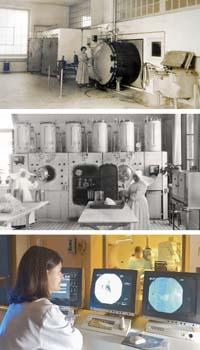

Taking into account the contributions of Carrasco and Epalza, the hospital was built. Other novelties were incorporated. For example, in a monograph of 1902 it is mentioned that the hospital would have a bacterio-physiological laboratory in which heaters and animals for experimentation would be included. Construction took place within ten years, from 1898 to 1908. In the opening year of the hospital, 3,213 incomes were recorded (1698 men and 1515 women), with an average stay of 31 days and a mortality of 10%.

Tuberculosis

If to travel in these hundred years must go hand in hand with a disease, that is undoubtedly tuberculosis. Tuberculosis mortality in the hospital was 41% in 1909 and in that year 235 patients were treated. In 1932, Dr. Arrospide was in charge of tuberculosis and had a 164-bed pavilion, the Revilla pavilion. In 1946 mortality was still 22% and the decline in mortality began to be observed from the years 50-60.

And so, because of the influence of epidemiological measures and antibiotic treatments against tuberculosis, the society considered that tuberculosis was an outdated disease. But not: A recent viral disease, HIV, which emerged in the 1980s, led to the growth of tuberculosis (among many other infections).

Typhus and typhoid fever (which are not well distinguished in the texts), being related to little cleanliness, were diminishing as society evolved, and only in the years after the war had a boom. Something similar happened with Navarre: at the beginning of the century 40 cases appeared, but then descended until its disappearance in 1980 (the exception occurred in the years 1918-1920). In the case of Diphtheria, the most worrying was its mortality, which in 1964 produced only four cases. Measles, scarlet and cough lost importance in the second half of the century, although every so often we could still see a slight increase due to an epidemic.

Declining infections

Because the persistence or frequency of infectious diseases decreased markedly from 1960, new organizations were also modified in the hospital and infection pavilions were used for other purposes.

Infectious diseases lost strength, the epidemiological measures of society and the development of antibiotics fence these 'flocks of microbes' and, although the flu epidemic of 1918 gave us a subject of remembrance, since humans have a memory like goldfish, before we realize, we were unconsciously introduced a virus in our lands to remember that we were too perishable.

Human beings are only one of the living organisms, and although the magazine The Lancet considered the diseases that can produce these tireless microbes exceeded in a year, this has been nothing more than our simplest dream.

In 1980 it was HIV. Later, SARS also entered the center and now we live in fear of the N1H5 bird flu. Nosocomial infections coexist with us and legionellosis and mycosis take the measure several times. Microbes have lived longer than we have in Darwin's evolution, and they will play spoon with us and they will worry us again when we think the least.

In the future, infections will travel with us, organize hospitals for it.

This article "Infections. History of 100 years in the Hospital of Basurto". The talk was given by Mikel Alvarez Yeregi at the annual congress of the Association for the Euskaldunization of Health.